Chalino, King of the Drug Ballad

I dig deeper into the true life of the Sinaloan icon

Para leer en español click aquí.

This story was updated on Oct. 3, 2025

In the rugged lowlands of Sinaloa, southeast of the city of Culiacán into the turf of the druglord Mayo Zambada, lies a mausoleum with the corpse of the beloved local singer Chalino Sánchez. Chalino emigrated to Los Angeles and built his career there so his life represents an alternate version of the American Dream. But he was fiercely loyal to his roots and kept returning to his homeland, where he was murdered in 1992 and, as his song Now After Death describes, a cold tomb awaited.

Chalino scored hits with interpretations of love songs he crooned in his unique gritty voice such as Nieves de Enero - which you can hear from Mexico City markets to North Carolina construction sites as well as YouTube where it has over to 500 million views. But he was the undisputed king of the narco corrido, or drug ballad, redefining the genre into a form that has since exploded in popularity.

As the narcos have become more bloodthirsty, unleashing massacres and mass graves, the music about them has garnered more heat, especially as kingpins actually pay to commission songs. Chalino represents a more refined era of valientes, or brave ones, pulling pistols from their cowboy belts. But his influence can be heard in the new narco ballads, as well as more commercial artists like Peso Pluma, who reached the top ten on Spotify.

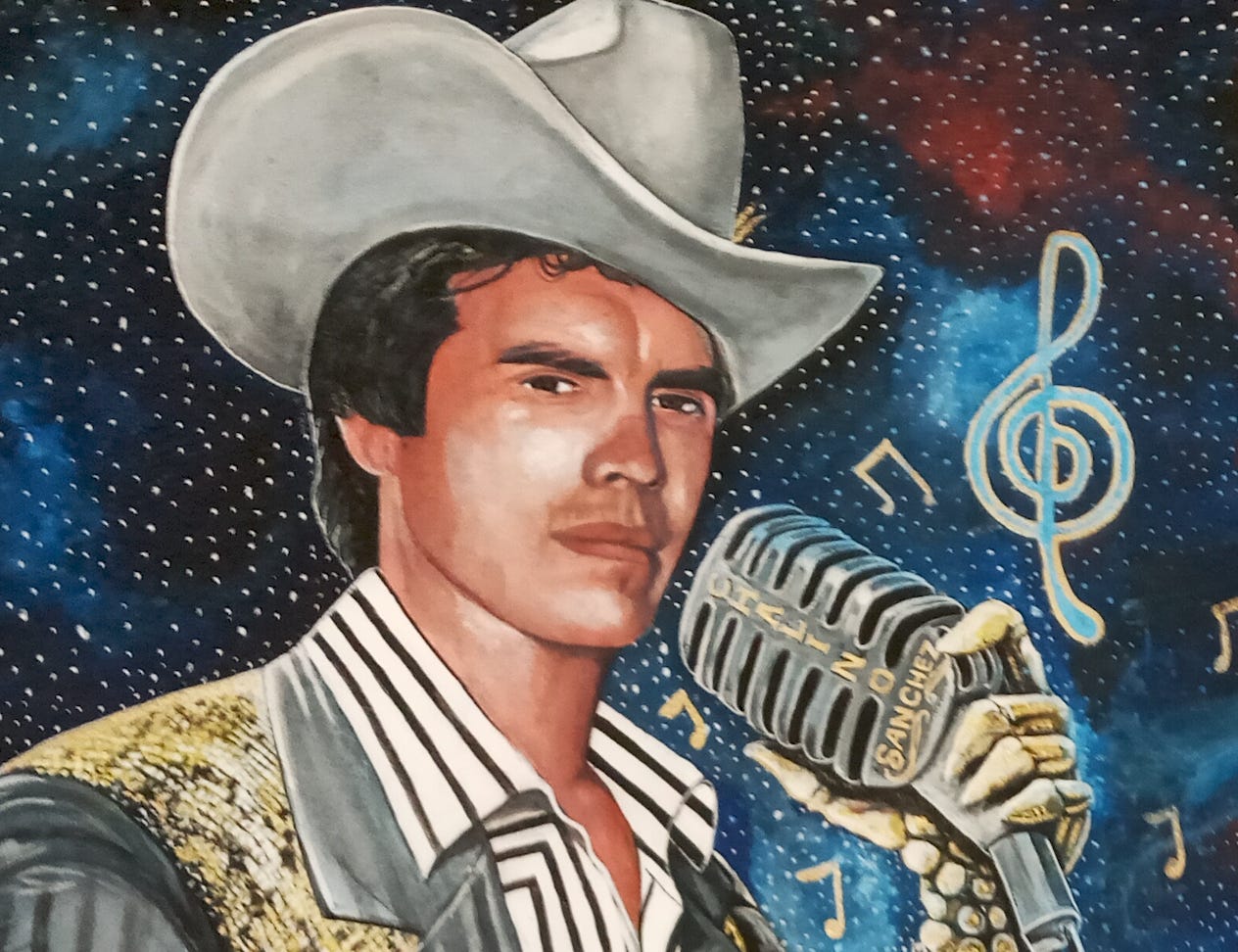

Photos adorn Chalino’s mausoleum. You see him wearing his tilted Texana hat, marking how he was a style icon who would influence a generation of young men on both sides of the border. You see him with his arm on the shoulder of his brother Armando, a broad and tough human smuggler, or pollero, who was murdered in Tijuana in 1984. The back wall is filled with a mural depicting Chalino under the moonlight, a pistol in his right hand and microphone in his left, a Sinaloan brass band playing. Across the mural cut the words, “Nunca Tuve Miedo” - “I was never scared.”

We used this phrase for a five part TV series on Chalino, Nunca Tuvo Miedo, released on ViX on June 30th, which you can find here. We cover the life of the icon with intimate interviews with his loved ones and fellow musicians and exclusive archive. As producer and writer, I spent a year traveling to Los Angeles and Sinaloa, getting drunk a fair few times on the sun-baked ranches with Chalino’s brothers and even a gunslinger who Chalino wrote a ballad for. They painted a vivid picture of the human behind the legend: hyperactive, bold, impulsive, smart, ambitious, hotheaded, romantic. In this piece, I lay out some of the revelations I learned, and I believe this is the most complete framework of the facts of Chalino’s life.

Journalist Sam Quinones wrote a fine and influential story on Chalino in his 2001 book True Tales From Another Mexico, which nails how he changed the LA culture, making the Sinaloa style cool for Mexican American youths. However, the family take issue with one very sensitive point in that and I dug up new details of Chalino’s early life, prison terms and shoot-outs. I also heard who could have killed him and why. For many in the milieu, it’s not a mystery yet it’s still dangerous to say out loud.

Rosalino from El Guayabo

Chalino was born Rosalino Sánchez Felix on August 30, 1960, on a ranch of wooden shacks called El Guayabo. While it sits in the municipality of Culiacán, it’s two hours out the city on dirt roads, not mountains like the home of El Chapo, but just as gangster, with drug crops and roaming gunmen. Chalino was the youngest of ten children, two girls who died as infants, followed by Lucas, Armando, Francisco (or Pancho), Regulo, Espiridión (or El Indio), Juanita and Lázaro. His brothers teased him calling him “Rosa,” so he switched to the name Chalino.

When he was about five, his father fell from a tree and smashed his head leaving him severely injured, later to pass from his wounds. His mother took her children to live with family on the nearby ranch of Las Flechas, where they survived toiling in the fields. “Chalino was my companion, we always worked together picking tomatoes,” Juanita remembers. “He sung and sung wherever he was. He seemed like a little bird…He always dreamed he would be a famous singer.”

Life in the countryside was tough with blood feuds between sprawling families sparking scores of murders and the “robbing” of girls from rival clans. One brutal incident would lead to Chalino’s departure. After half a century, the family are still sensitive in giving details, but an offense was committed against Juanita and at fifteen, Chalino carried out an act of "venganza,” or revenge, on one of the perpetrators, which forced him to flee.

The incident is described in the ballad, El Corrido de Rosalino. “He left his native land; because that was his destiny; for defending his family; that was what Chalino fought for.” Chalino sung the song about himself but his brother Indio actually composed it, Indio tells me.

Chalino went to Los Angeles in the late 1970s and worked in fields and restaurants but longed for more, his sister says. “If they sent him to clean a restroom, he would say, ‘No compa, I didn’t come here to clean toilets, I came here to be a famous artist.’ ”

With stardom still allusive, Chalino worked with his brother Armando as a pollero, smuggling migrants over in Tijuana. I found a fellow pollero, nicknamed Chaparro, who said they would drive migrants over the border from the Libertad neighborhood, charging $200 a head.

In 1980, Chalino did his first prison stretch of three months over a non-fatal shooting. Locked up in Tijuana’s crowded Mesa penitentiary, he met inmates including the trafficker Rigoberto Campos, who would later be assassinated in his Gran Marquis and Chalino would sing about it.

Out of prison and back in Los Angeles, Chalino met his wife Maricela, a hard working woman who was outside of the gangster life. He courted her like a gentleman, rapidly fell in love, and they married. Yet Chalino was again arrested and sent to prison, this time in LA County for a drug offense, and his son Adán was born in April 1984 while Chalino was behind bars.

It was in his American prison cell that Chalino became serious about composing, penning one of his first verses about Bautista Villegas, an outlaw from Sinaloa who he referred to as an “uncle.” Like many traditional corridos, it ends with the the protagonist perishing in a hail of bullets. “Sixty shots to the body crossed him; various calibers took away his life.”

When Chalino got released, he had three or four complete songs, brother Regulo says. “I took the paper and I read them. I thought they wouldn’t work out. But oh yes they did.” A happy photo shows Chalino at this moment, just out of jail and partying with his brothers, wife and newborn in his apartment in Inglewood. But right after, calamity struck again when his brother Armando was murdered in Tijuana.

The killing took place in the hotel Santa Rita, which still stands, a cheap dive a few blocks from the US border. Armando was playing cards with other polleros when an argument broke out and Armando beat a man down with his fists. The loser of the fight got a gun, snuck into Armando’s room and shot him in his bed.

Chalino wrote another of his early corridos in honor of his beloved brother who he so admired. “A brave man died, a coward killed him; without giving him any time, he gave him seven bullets.”

The Dirt Road to Stardom

Chalino carved his path to fame as a true grinding underground artist. He crooned in cantinas, sold cassette tapes out his car, and built a distribution network from Hollywood to the Sinaloan ranches.

He initially sung out of tune in his gravelly voice. “I don’t sing. I bark,” he joked. But he had a charisma that won over the drunken revelers. “They heard him sing and they applauded,” says Heriberto “Kiko” Olguin who played with him in his early years. “He said to me, ‘It feels nice when they applaud you doesn’t it.”

Many of those revelers were also migrants from the Mexican countryside and Chalino made them feel at home. He unashamedly used local slang, like “muncho” for “mucho” and “naiden” for “nadie.”

Word went round and characters from the LA underworld began commissioning Chalino to write songs, often paying in jewellery or firearms (which Chalino truly loved). Corridos had traditionally been about fallen heroes, but now he was writing about living people for payment.

“When that caught on that became the new corrido genre,” says Elijah Wald, music writer and author of Narco Corrido. “So that you started having all these songs that didn't tell a story anymore…they were just ‘He's the greatest. He's the strongest.’ ”

Chalino recorded his first albums with Kiko at the small San Angel recording studio on Olympic Bulevard and got cassette tapes banged out at a factory. He sold them at car washes, swap meets and through small stores. But he also went back to Sinaloa and hooked up with a music seller called Manuel Soto. Soto’s stall is in a Culiacán market where farmers come to buy tools and fertilizer and would pick up a tape. It carried Chalino’s sound to the ranches he hailed from. “People asked for a lot of his cassettes, because he was, how do you say it, a phenomenon,” Soto says.

Chalino’s career went up a gear in 1990. He started recording with one of Mexico’s best accordion players, Nacho Hernández, and markedly improved his singing. His voice was now in tune but still raw and disctinctive, reminiscent of a Bob Dylan. He began performing at two legendary LA clubs, El Parral and El Farallon. Founded by migrants, they became the Mexican regional music equivalents of Studio 54 , with the top artists, women dressed up to the nines, and men splashing out on expensive tables and bottles.

Chalino was one of the biggest draws, famous for coming on stage with his gun on his hip; an authentic gangster singing about gangsters. But the persona that drove him to success would contribute to his downfall. “Valientes cannot be musicians,” says Nacho. “Because if I am a valiente, they will kill me in the end.”

Shooting To Fame

The first blood was spilled in January 1992 when Chalino did his infamous show at the Arcos venue in Coachella. The crowd was hot, passionate and rowdy, requesting songs into the early hours. As the band launched into a tune, crowd member Eduardo Gallegos jumped on stage, pulled out a large .44 caliber pistol, and fired at Chalino. The singer took two bullets but managed to pull out his gun and fire back. A total of ten people including Chalino and Nacho were injured. A shot hit another member of the audience, René Carranza, who died of his injuries. The crowd pounced on Gallegos and beat him down.

It’s unclear why Gallegos went for Chalino. I wrote to him in prison but he declined to take part in the series. Nacho says that Gallegos could have been angry because he had requested a song but Chalino didn’t play it. However, the county prosecutor Henry Martinez, says that wasn’t mentioned at the time of the investigation and they couldn’t find an explanation but believed there could be a hit.

“Mystery shooter,” he says. “Our belief was that there was probably a contract, a hit out on [Chalino] for whatever reason, probably involving drugs, heroin, specifically.”

In a recent revelation, a Sinaloan hit man based in California, called Jose Manuel Martinez, alias El Mano Negra, claimed to have taken part in the shooting, saying it was a contract hit that went wrong. “[Chalino] had more lives then a cat,” he said. (You can read the full interview with Mano Negra on CrashOut here.)

What was clear, Martinez said, was that the ballistics showed that it was a bullet from Chalino’s gun that killed Carranza. Still, as Chalino acted in self defense, he was not charged. Instead, they convicted Gallegos of starting the shoot-out that led to the death. “We needed to use this little-known theory called the Provocative Act Doctrine,” Martinez says. “That's called when you transfer that criminal responsibility.”

Chalino was taken to hospital in a coma and Maricela sat by his side for days with a gun before he awoke. She was terrified someone could come in to finish Chalino off. Security stopped one guy who claimed to be a relative and another dressed as a woman getting into his ward.

When Chalino finally regained consciousness and got out of hospital he found his fame was on the next level. The incident was featured on American TV and in newspapers. The cholos in Los Angeles who listened to hip hop all began bumping Chalino in their trucks. “They said, ‘We don’t need to idolize the rappers who are gangsters. Now we have our own gangster and it’s Chalino Sánchez,’ ” says DJ Pepe Garza.

This comparison with gangster rap has been made plenty. Chalino certainly gained fame after NWA and others had blown up. Some call him a Tupac or an Eazy-E. A difference is the Mexican narcos would become bigger and more violent than the street dealers of Los Angeles ever were.

Returning Home

There was fear Chalino wouldn’t be able to sing because a bullet had punctured his lung. But by March, he was performing again and more popular than ever. When he played a quinceañera in Compton, so many people showed up there was a near riot. He packed the Parral leaving queues round the block. He could charge thousands of dollars to compose corridos.

He gave what might be his only TV interview in Tijuana just two months after the shooting. He is full of life and wit and does a boisterous performance. “They think I have died,” he says, “that there has been a wake, that I have been buried but…” and he points to himself.

As the man of the moment, he signed a deal with Musart, one of Mexico’s top labels. It was worth a fraction of what his records would sell for but it gave him enough to buy a home for his wife and two children in Paramount; he seemed to be putting his affairs in order like he knew something could happen.

In May, he went back to the Sinaloan city of Culiacán to play a profitable show at the Bugambilias salon. The night before, a woman called his home demanding to speak to Chalino. When Maricela answered and said he wouldn’t talk, she warned that Chalino should not go to Culiacán as he was in grave danger. Chalino shrugged it off and said not to worry.

The concert was packed but tense. Brother Pancho says that looking back Chalino knew something would happen. “The truth is that Chalino had no fear,” he says. The concert was filmed and in one moment a note is passed to Chalino on stage and he nervously wipes his brow as he reads it. Many believe it was a threat. But the crowd also gave notes with the names of songs and the paper has never been found.

Chalino left the venue with Pancho, Indio and some women. A few blocks away, a Suburban cut them off and men stormed out with guns. Pancho says they were dressed in plain clothes not police uniforms. First they tried to take Indio but after he said he wasn’t the star they zeroed in on Chalino. “They grabbed him and took him and put him in the car and went,” Pancho says. In the morning, two campesinos found his body by the canal, handcuffed with two bullets in the head. He was thirty-one and at the peak of his career.

Ya Después De Muerto

Three decades later, the murder remains officially unsolved, but then so are 90 percent of homicides in Mexico. People in Sinaloa openly talk of a name of an assassin who pulled the trigger, who has now been killed but has sons, and a drug trafficker who ordered the hit. But the family don’t want more problems.

Chalino’s death made his records sell. Millions of adoring fans sung along to his songs and countless immitators followed his style. His son Adán began singing at just ten years old and as a teenager blew up to have his own promising career, being the first Latin artist to play the Kodak Theater and filling it out. But then he died in a car crash in 2004 at just 19 years old. Maricela lost a husband and a son. She continues to work to defend their legacy.

Chalino’s face is painted on murals and t-shirts, an iconic image that, as Wald says, is like a cross between between Scarface and Zapata. The world of narco corridos today has got much bigger and bloodier and is worth millions. But that is for another story. I’ll end this one with the lyrics of Chalino’s Ya Despues de Muerto, which could be translated as, “Now After Death.” He wrote a lot about people dying. But this one makes you realize it will happen to you too.

“Now after death, now after death,

“Now after death, it’s not the same,

A cold tomb, is what awaits you,

Everything has finished, you have come to the end.”

Photos by Ioan Grillo.

Copyright Ioan Grillo and CrashOut Media 2023

With the genre exploding now more than ever, you went and did a superb job on the lines between narcocultura, "official" history, and history. I think your work on narco war in general similarly seeks truth beyond ideology. When the border crisis was no longer useful as a political instrument, from the left AND right (whatever they mean), you kept accurately reporting the crisis that was brewing in Juarez still. Suddenly the 24/7 coverage on all mainstream sites stopped. Chalino, the man, which oftentimes is lost in his myth. You're truly a truth-seeking journalist. Saludos desde Juárez.

Great stuff Ioan. I first heard a Chalino song a Mexico City bus (pesero) in 1996. I was living off the Perisur near TV Azteca, and on Sundays always travelled by bus from there to either San Angel or to Coyoacan. Our trip back was always late afternoon and required catching a special bus in San Angel. It was approximately a 20-25 minute trip back to our stop at the foot of Unidad Elias Calles and there were no stops in between. The driver always played loud music, and on one occasion he played a song that was so distinctive that I walked to the front and asked him who was singing. It was Chalino Sanchez and I bought my first Chalino CD the next time I was in Coyoacan and still have it.