Did The U.S. Army Use Sinaloa Dope?

Evidence is confusing on the alleged World War II pact between Washington and Culiacán

Para leer en español click aquí.

In a moving scene in the blockbuster war movie Saving Private Ryan, soldiers try to save the unit medic Irwin Wade who has been blasted in the abdomen by machine-gun fire. After giving him a first morphine shot, the troops ask Wade what else they can do. Realizing he is a gonner, Wade utters “I could use a little more morphine.” They reluctantly stick in a second dose and Wade floats to a dreamy death.

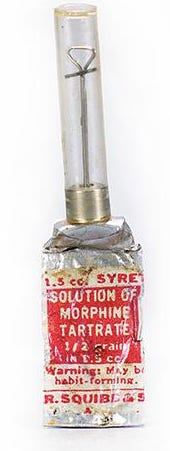

What were called ‘morphine syrettes” packed into handy syringe-like kits were indeed used by U.S. troops in World War II helping suffering soldiers ease the pain before they got better medical help. Made by E.R. Squibs & Sons, the kits came with the warning, “May be habit forming” and as the DEA museum says: “After the war, people bought—and even stole—surplus medical kits for the morphine inside. Many turned to heroin when the surplus morphine disappeared.”

Still, the pain killer was crucial to the war effort and only possible with its raw ingredient, opium. Which gets to the contentious question of where exactly the United States got its opium supply. And did any of it really come from Sinaloa, the cradle of Mexican drug trafficking?

The belief that Washington and Sinaloa made a World War opium pact, kick-starting the narco trade south of the border, is held widely across Mexico. In the Mexican army’s museum of traffickers (the infamous “narco museum”), it states as fact that U.S. agents went to Sinaloa to buy opium gum, which is scraped from white and pink poppies that grow in its mountains. The late U.S. academic George Grayson told me a Sinaloa governor had boasted about the pact on a visit. Several prominent Sinaloan intellectuals have cited it, including the writer Antonio Haas, who laid out the plot in a 1988 article.

As the story goes, the United States needed colossal amounts of opium for the conflict, especially in the Pacific sphere, but traditional sources such as Turkey were squeezed by German U-Boats, as well as competing powers demanding “God’s own medicine.” So Washington turned to Sinaloa, which lies less than 500 miles south of the U.S. border.

The tale plays to an emotive view in Mexico that the narco trade is the fault of the gringos. America’s voracious appetite for drugs and guns adds to this argument. But is it true?

Sociologist Luis Astorga, perhaps the most eminent Mexican academic on the drug trade, shed doubt in his landmark 2003 work Drogas Sin Fronteras. “The supposed pact forms part of Sinaloan mythology about drug trafficking [but] it probably originated in state government offices in the era or in other local sources of the rumor mill.”

British historian Benjamin T. Smith, a friend of CrashOut and author of this stellar piece, also doubts the deal. In this article he digs up a treasure trove of fascinating documents, some of which I reproduce below, that he argues show how the myth was generated.

Personally, I think the evidence paints a more mixed picture. It’s clear that the Sinaloa drug trade didn’t begin in World War II, as opium was grown there before, likely brought by Chinese migrants as early as the nineteenth century. And there is no document showing a formal deal between Washington and the Mexican federal government for war opium. But the idea of U.S. agents venturing to Sinaloa to buy gum for war morphine looks possible and there is a lot of smoke if no fire. Here I go through the clues on whether U.S. soldiers bleeding far from home really had their pain numbed by Sinaloa dope.

Morphine Made In Brooklyn

What is now the Bristol Myers Squibb Company began in the 1850s when naval surgeon Edward Robinson Squibb rented a brownstone building in Brooklyn as a lab. During the Civil War, he supplied the “Squibb Medicine Chest” to the Union army, which included morphine. (Thousands of soldiers also got “morphine mania” after that conflict). As the years and wars rolled on, Merck & Company, Mallinckrodt, and New York Quinine and Chemical Works also worked on opiate products.

Sorry folks, you need to subscribe to read this story. But it’s only the price of a cuppa coffee and you get the complete archive including exclusive interviews with top players and maps of cartel territory. And now is a great time to subscribe as we will be following these issues with detailed reports you can trust as big things break in the coming months.