The Empire of Los Chapitos

A postcard from Culiacán

Sinaloan “mota,” north of Culiacán.

We run into the punteros by the tollbooth on the road from Mazatlán into Sinaloa’s colorful state capital of Culiacán. They are operating so brazenly they have even put up a tarp to shield themselves from the punishing sun. An older guy with a baseball cap and mustache stands under the tarp with his open palm above his belt buckle in the pistol-packing pose. A younger guy with a mop of black hair buzzes over to us on his motorbike and asks what we are up to.

Punteros is a term you hear more in Sinaloa, the cradle of Mexican drug trafficking, than in other states. It is often used in place of halcones, the lookouts for the cartels, but the punteros of Culiacán are a little different. Halcones in other Mexican cities usually adopt a low profile as they keep their eyes open for anything that moves and report it up the chain by cellphone or radio. The punteros in Culiacán can be more overt, so marking the territory, or el punto. They usually have motorbikes and are often armed. And they frequently sell drugs at their point as well as providing eyes.

We are filming a shot of the highway with a drone, which is grabbing their attention. When the puntero comes over, I explain we are making a documentary series which is just about music and he looks over the shoulder of the cameraman at the images from the sky. Our local producer gives the puntero a fist bump and asks what he is selling. The puntero flashes bags of weed and wraps of cocaine and asks if we want to buy.

I have been coming to Culiacán since 2008 and made four trips here over the last year for this series. It’s changed. When I covered it in the 2008 to 2010 period, there was a bloody turf war between Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán and his blood-brother turned mortal enemy Arturo “El Barbas” Beltrán Leyva. There were more bodies being dropped, and I spent days sprinting to stoplights and roundabouts to cover multiple executions.

Today, there are less murders but there is the feel of a more overarching narco control. This change is due to various shifts in Mexico’s crime environment but a big factor is the rise of the sons of El Chapo, known as Los Chapitos, who now dominate the city. As people here don’t like to say their name loudly in public, they are referred to as “the juniors.”

The flagrant nature of the punteros is one visible difference. Perhaps an even bigger novelty is that entire dispensaries of high-grade marijuana have opened up. Mexico’s Senate is taking forever in approving a bill to legalize cannabis, but in Culiacán they have gone ahead and effectively legalized it themselves.

I go into one such dispensary in a second-floor apartment. It is decked out like you are in Los Angeles with jars of herb marked as Candy Kush and Strawberry Banana and Jack Herer. They offer plastic packets of marijuana cookies and candies and oils. And they have ready-rolled joints, laughably labeled as “sicarios.” The guy serving is in his early twenties and could pass as a student.

I don’t know who really owns the place. It may be nothing to do with the cartel. But it would seem tough in a city like Culiacán if it didn’t at least have the approval of the real power.

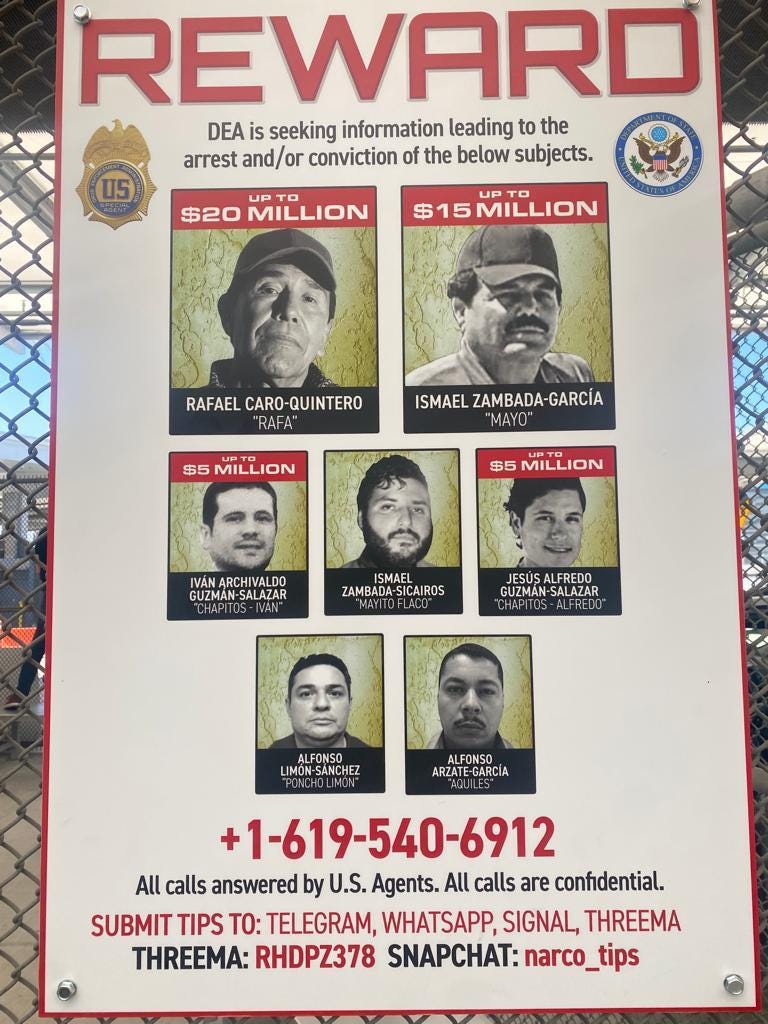

A wanted poster for Sinaloa Cartel figures at the Tijuana-San Diego crossing.

What is known as the Sinaloa Cartel has likely never been a tight pyramidal organization but more like a federation of drug traffickers. El Chapo was probably not the single supreme leader over this whole network, a charge his lawyers disputed at his trial in New York. But he was a figurehead for the cartel, a powerful gangster that others swore fealty to, and he had total domination of certain areas, like parts of his mountainous municipality of Badiraguato and chunks of Culiacán.

El Chapo left a sprinkling of children with various women, but the “Chapitos” tends to refer to four of them: Ivan Archivaldo, “El Chapito,” (39), Jesús Alfredo, “Alfredillo” (36), Joaquín “El Guero” (36) and Ovidio, “El Raton” (32). When El Chapo was extradited in 2017, some of the elders thought these privately educated “juniors” might not be as tough as the old-school campesino traffickers. But first they outmaneuvered and outgunned their father’s lieutenant Damaso López. Then they beat the Mexican army.

The so-called “Culiacanazo” of 2019 – when Mexican soldiers arrested Ovidio and hundreds of cartel gunmen took to the streets to force his liberation – was the real graduation for the Chapitos and consolidated their power in the city. A narco corrido, or drug ballad, about the incident was finally released last October. Assuming the voice of Ovidio, it apologizes for the disturbance but boasts that a Guzmán is not intimidated by the government. It seems impossible that the song could have been released without permission from its subject.

“Soy el raton” has over 23 million views on YouTube and can be heard in Culiacán along with other corridos blasting from pickup trucks, SUVs, and the now fashionable “buggies.” Pronounced in Culiacán like “boogies,” these are quad bikes with roof frames and colossal sound systems that Culichis speed around on dressed in flamboyant racer gear.

Culiacán buggies in action.

In June, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador remarked that Sinaloa has less murders because of the presence of a powerful cartel. “There are places where a strong group dominates and there are no confrontations between groups and so there are less homicides,” he said. “Sinaloa and Durango aren’t in the states with the most homicides because there is just one group.”

He is right at least that there are less murders in Sinaloa. Last year, there were officially 600 homicides, making it the 15th most murderous state in the country per capita. Back in the battles of 2010, it suffered more than 2,000 killings and was the second most deadly entity.

There are still tensions within the Sinaloan mob though. Rafael Caro Quintero, the infamous narco from the 80s who likely bribed his way out of jail, clashed with the Chapitos in Sonora. His rearrest in northern Sinaloa in July was celebrated by American agents furious about his role in the murder of the DEA’s Enrique Camarena. But by his final days on the run, Caro was probably a minor player without influence in Culiacán .

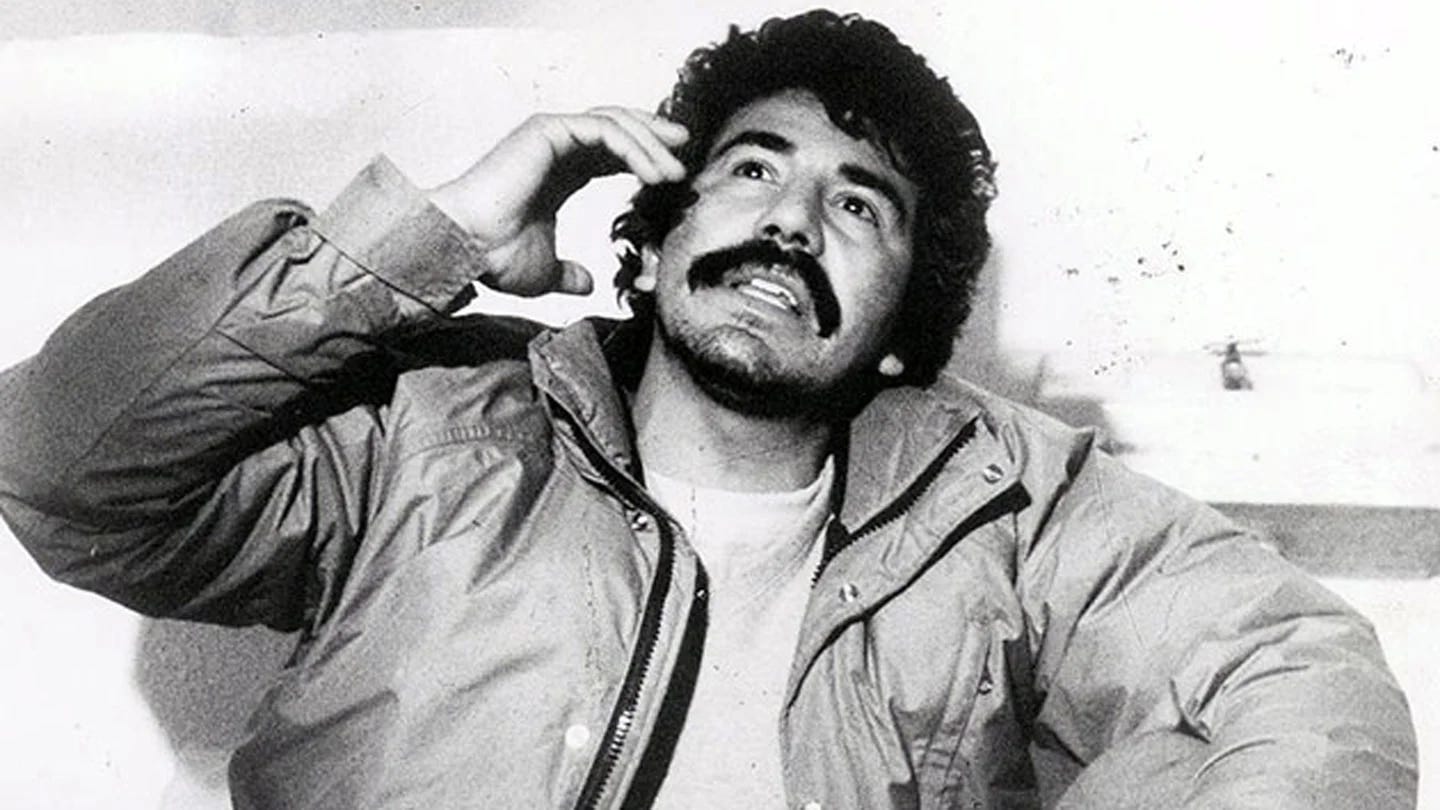

Caro Quintero, then and now.

More significant is the potential friction between the Chapitos and the old Sinaloan godfather Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, who many in Sinaloa claim was even more powerful than Chapo. I hear different versions of how bad this tension is. There are allegations that Mayo’s people were too slow coming to the Culiacanazo, or that he sided with Caro in Sonora. But in Sinaloa itself, both factions appear to be living side by side without major bloodshed, including in Culiacán.

Some call it a “cold war.” In Sanalona, a town that sits between the strongholds of the Chapitos and of El Mayo, I hear that gunmen from both factions party at a restaurant-bar on Sundays, but they stand on opposite sides staring each other down and firing shots in the air.

El Mayo’s core territory is to the south of Culiacán around the village where he grew up, an area of rough arid countryside that is not high mountains like El Chapo’s Badiraguato but is just as narco. I spend time there on various trips, talking especially to old musicians. Many of the men on the ranches snort cocaine as they sip their Tecate beers. One guy is still snorting at eighty years old, buying wraps of cocaine from his village grocery store.

They sell a variety of presentations of cocaine in Sinaloa. These include: “lavada,” which goes through an additional process to give it sweet flavors; “machaca,” which they admit is mixed down; “cuadrada,” which comes in a square, supposedly cut straight from the the brick it was forged in; and simply the classic “original.” Some wraps of cocaine bear the symbol of a scorpion, which they say is the brand of Los Chapitos.

The dealers I find offer cocaine and weed, but I hear the cartel has banned the selling of fentanyl in Sinaloa because of the harm it has been doing. Of course, the narcos have no such qualms trafficking huge quantities of the deadly substance to the gringos, and with a record of over 100,000 overdose deaths in the U.S. last year, this is spurring the drive of the DEA to go after them.

On one trip down a dirt path, my local producer’s car gets stuck in the mud. The two of us unsuccessfully try and push it out until an SUV drives up behind. I think we are about to get rescued until I see it is full of guys in combat gear with AK-47s.

I give them the same story about being a journalist just doing a project on music, and they try and drive past us. But then they get stuck too, pressed up against our vehicle. The boss looks to be in early twenties and his three gunmen could be late teens. He is laughing at the situation and radios for a guy to come in a pickup truck and pull us out the mud.

Mexico’s narco war is truly tragic. But sometimes it can be surreal.

Bullets, beer and flowers. A tomb in rural Sinaloa.

Copyright Ioan Grillo and CrashOut Media 2022

Definitely worth following Ioan Grillo. He was one of the first English language journalists to cover Narco Mexico, and he remains amongst the most observant. To top it off, he writes clearly and succinctly.

Thanks for the fantastic read. You mentioned these corridos, they have been widely popular nowadays many of them revisiting acts such as el Culiacánazo, El Ratón. Another song widely popular, JGL. (Joaquin Guzman Loera) how are these songs “OKd” for release? Both these songs are highly popular and some of these are not taken lightly in different states.

Keep safe, thanks again.