America's First Drug Cartel Was Not Colombian or Mexican; It Was The Italian-Jewish Mob

The image of the U.S. mafia shunning drugs is pure Hollywood. Lucky Luciano and Arnold Rothstein built America's narco network.

Para leer en español click aqui.

In one of the most iconic of so many iconic scenes in The Godfather, the aging patriarch Don Vito Corleone addresses the leaders of New York crime families in a conference of kingpins (which really does happen). Played in spades by Marlon Brando, the Don laments the murder of his son and then lectures them about why he doesn’t deal drugs.

“I believe this drug business is going to destroy us in the years to come,” Corleone says in his gravelly rasp. “I mean it’s not like gambling or liquor, even women, which is something that most people want nowadays and is forbidden to them by the pezzonovante [big shots] of the Church…And I believed that then. And I believe that now.”

It’s a fascinating portrayal of a crime boss who cares. But you need to take into account that while The Godfather was being filmed, the movie makers were under pressure from real mobsters, as is revealed in the book, Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli. Producer Al Ruddy had to negotiate with New York kingpin Joe Colombo to make the flick more amenable to them. To compromise, the film makers took out all mentions of the word “mafia” (as the mob is commonly known to outsiders) and “Cosa Nostra” (as they call themselves). Several genuine mafiosi got into the cast, including Lenny Montana, a six-foot-six wrestler and Colombo enforcer who played Luca Brasi and knocked around the producer Ruddy. And the depiction of the mobsters became decisively more flattering.

The gangsters ended up loving The Godfather as much as America and the world did, and it popularized the idea of glamorous mafia dons who follow a code of honor - rather than ruthless drug traffickers.

It’s a comfortable fiction that has allowed U.S. mobsters from a “golden age” to be celebrated while narcos over the Rio Grande today are billed as Public Enemy No. 1. Yet the reality is that homegrown criminals - with Italian, Jewish and Irish roots - built up a network that smuggled in narcotics from overseas and provided it to every U.S. town and city. These entrepreneurial crooks helped give the United States the highest number of drug users in the world and laid the foundation for Colombians and then Mexicans to move in.

“I know there’s this narrative that is out there to this day that the Italians have a deal or die policy, if you deal we kill you,” says Scott Burnstein, a writer on the mafia who has interviewed ranking members. “Well that was all PR, a way to sell themselves as Robin Hoods and protectors of their community to the public, to the prosecutors to the politicians, when the reality from day one, every major mob family, every major mob boss, was steep and up to their nose in narcotics rackets.”

This mob-narco network is the subject of an enlightening new documentary directed by Seth Ferranti and featuring top mafia writers in sharp suits including Burnstein and Christian Cipollini. It’s apt title: Dope Men: America’s First Drug Cartel.

Heroin and Booze

Calling these mobsters a “cartel” is not just wielding the language of today to re-label a phenomenon of the past. It’s been forgotten that the first uses of the term cartel to describe drug traffickers and organized crime were likely in reference to the mafia. A New York Times story in 1951 is headlined “5 in New York-Canada Cartel Held” and reports heroin trafficking to New York and Montreal. The traffickers, it says, are part of “an international narcotics cartel headed by deported vice overlord, Charles (Lucky) Luciano.” In 1954, the book Syndicate City was published with the subtitle, “The Chicago Crime Cartel and What To Do About It.”

However, the mob’s narco network goes back further still, emerging in the roaring twenties. The mafiosi famously bootlegged booze after the 1919 Volstead Act established prohibition of alcohol. But they were also shifting heroin after it was restricted by the 1914 Harrison’s Narcotic Tax Act.

When people hear about organized crime in this era, they immediately think of Italians, with Al Capone shooting to stratospheric infamy. But there were also top Jewish mobsters such as Arnold Rothstein and Irish hoodlums like Jack "Legs" Diamond. These Italian, Jewish and Irish gangsters together formed a network of drug traffickers.

Rothstein, who was reputed to have fixed the 1919 World Series (which may or may not be true), was known as “The Brain” of the operation and was sending guys to Europe and China to buy heroin from at least 1923. “He saw the opportunities very early on,” says the writer Cipollini. “Rothstein’s role was a venture capitalist. It’s about the money.”

Yet it was Rothstein’s friend Charles “Lucky” Luciano who had the vision to create a structure across the United States to manage organized crime and distribute its drugs. In 1931, he set up the so-called Commission which brought together Italian mafia bosses including Capone and Jewish mobsters like Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Siegel.

“Luciano was a visionary, a pioneer, with very few equals,” says the journalist Burnstein. “Luciano’s vision was, ‘Lets take over the whole country, and let’s have a home office if you will, in New York City, and a board of directors in New York City. But we are going to have 26 different satellites spread across the country, going from New York to Los Angeles and Chicago and Detroit all the way to Texas and Louisiana and Florida.’ ”

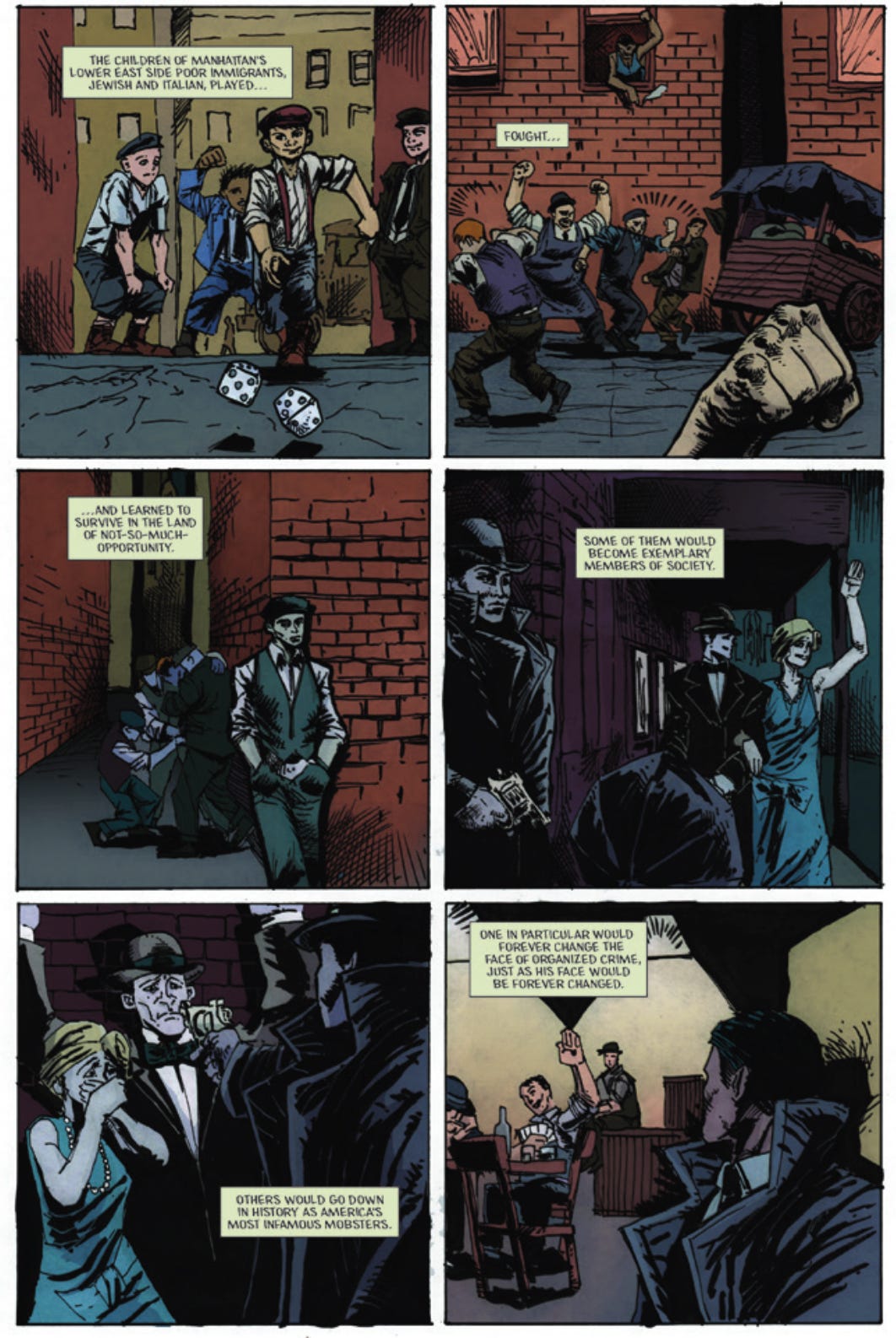

Cipollini wrote about Luciano’s rise in a biography and more recently a graphic novel, Lucky: A Scar Is Born. He describes how Luciano grew up in New York’s Lower East Side among boys of mixed backgrounds who were poor but close to wealth and brimming with ambition. “It was a lot of Jewish and Italian crunched in there that had to either fight or get along,” he says. “Those were the ones who were like, ‘We’re gonna get the American Dream one way or another.’ ”

Working With The Government

While prosecutors got Capone for tax evasion, they nailed Luciano on vice. Convicted on 62 counts of forcing prostitution, Luciano was sentenced to 30 to 50 years in 1936. But less than a decade later, the kingpin was free and sailing for Italy. He achieved this miraculous reduction in time by lending a hand to the U.S. government in its so-called Operation Underworld of World War II. Luciano first used his control of the New York waterfront to seek out German saboteurs and then gave intelligence and mafia contacts to aid the U.S. invasion of Sicily.

Operation Underworld marks the beginning of a sordid history of U.S. agencies working with drug traffickers. And as in other cases, cooperating with the government didn’t cure Luciano of committing crime. After he was freed, Luciano based himself in Naples and organized heroin trafficking into the United States. The narcotics business had been put on pause by the war but by the 1950s it was stronger than ever.

Whereas the mob in the 1920s was multi-ethnic, by the 1950s it became more solidly Italian, which is why that image is so prominent today. “Post war, a lot of the Jews had assimilated out of that racket and the Italians, they grabbed onto it with both hands,” says Cipollini. This period of the fifties to the seventies is considered the golden years of the Cosa Nostra in America. It’s also when drug consumption rocketed and street crime exploded.

Yet all good things come to an end. From the 1970s, the FBI hit the Cosa Nostra hard, with undercover agents like “Donnie Brasco” and racketeering conspiracy charges or RICO, brought in specifically to target the mafia. Meanwhile, African-American crews like the Black Mafia Family muscled into street drug selling and Chinese triads, Colombians, and then Mexican cartels took over trafficking.

“There’s always a new kid on the block just waiting for their chance and whatever factors, variables come into play makes one start to come down and another rises,” Cipollini says. “I equate it to every empire in history.”

Copyright Ioan Grillo and CrashOut Media 2023

Let's go further back to 1898 when the drug company Bayer was promoting heroin as the new miracle cure for all kinds of ailments for adults and children! Even Sears Roebuck sold the Bayer's "miracle drug". By 1924 there were over 200,000 heroin addicts in the United States alone. Maybe you can call the pharmaceutical industry the first real drug cartel and still continuing that fine tradition today.

I always heard, from reliable sources who were around in the 1970s (+ even 1960s) that the reason the Italian/Sicilian outfit lost its hold on crime was not because the Feds broke it up, but because the bosses stopped "making" new soldati; preferring instead to send their sons to college and into legitimate, less brutal businesses. The sons with no other options were a pretty poor lot, for many reasons; and had less of an exclusively "ethnic" community to extort and live off. They got into drug trade heavy, but were bad at it; and wound up busted, addicted, or dead in disputes with outside competitors and their own suppliers. The other, newer, hungrier ethnic outfits supplanted them easily. It's my belief that "Mafias" in America are a stage in the development of immigrant cultures; formed first for community self-defense, then expanding into lucrative "rackets" where their tools of force are useful. The prosperity they generate springboards their second or third generation into American upper-middle-class identity, and they leave the rackets behind where the next group takes up. It worked for the Irish, Jewish, and Italians; and the Russians, Albanians, and various Latinx ethnicities have it now.