Carlos Lehder’s Vida Loca in the Medellín Cartel

In an exclusive interview, the former cocaine king discussed Pablo Escobar trying to kill him, his Netflix portrayal as a narco Nazi, and testifying against Panama’s Noriega

Para leer en español click aquí. This is a text story based on hours of interviews with Carlos Lehder; you can also see a video of part of the interview here.

When Colombian cocaine king Carlos Lehder was called in to see his associate Pablo Escobar at his hacienda near Medellín, he knew it could mean trouble. The drug lord Escobar had been killing off other members of the so-called Medellín Cartel over money and personal beefs, and sent hit men dressed as police to assassinate one trafficker along with his secretary, maid, chef and even dogs. And when you saw Escobar, you never knew what mood he would be in.

“He will bring people in front of him and his demeanor, his language, his insults, it was very impacting to the point that some of these guys will be trembling, physically sweating in front of him because he was angry at them,” Lehder tells me.

Lehder’s life was saved, however, because one of Escobar’s bodyguards, who he was friends with, warned him to be careful and gave him a new revolver. When another of Escobar’s killers moved against Lehder, he would be able to fight his way out.

Now 75-years-old, Lehder recounts the story as we sit in a hotel in the hills near his hometown of Armenia, Colombia, exotic birds chirping in the trees. Lehder was one of the top players in the Medellín Cartel and has been cited by various outlets, such as Business Insider, as minting a personal fortune of $2.7 billion from flying white powder into the United States during the cocaine boom of the eighties. While that figure is likely an exaggeration, Lehder certainly took over the private island of Norman’s Cay in the Bahamas to use as a trafficking hub, and he tells me they paid off the Bahamian prime minister, among various corrupt presidents and guerrilla armies they worked with.

Most of the Medellín Cartel bosses are long dead, including Escobar himself who a crack team of Colombian police gunned down in 1993. But Lehder survived thanks to being arrested in 1987 and locked up in a top security prison in the United States. He was sentenced to life without parole plus 135 years, and expected to die in a cell. But he made a deal to testify against the former president of Panama, Manuel Noriega, another affiliate of the cartel, and in return found his freedom after 33 years and moved back to Colombia in March.

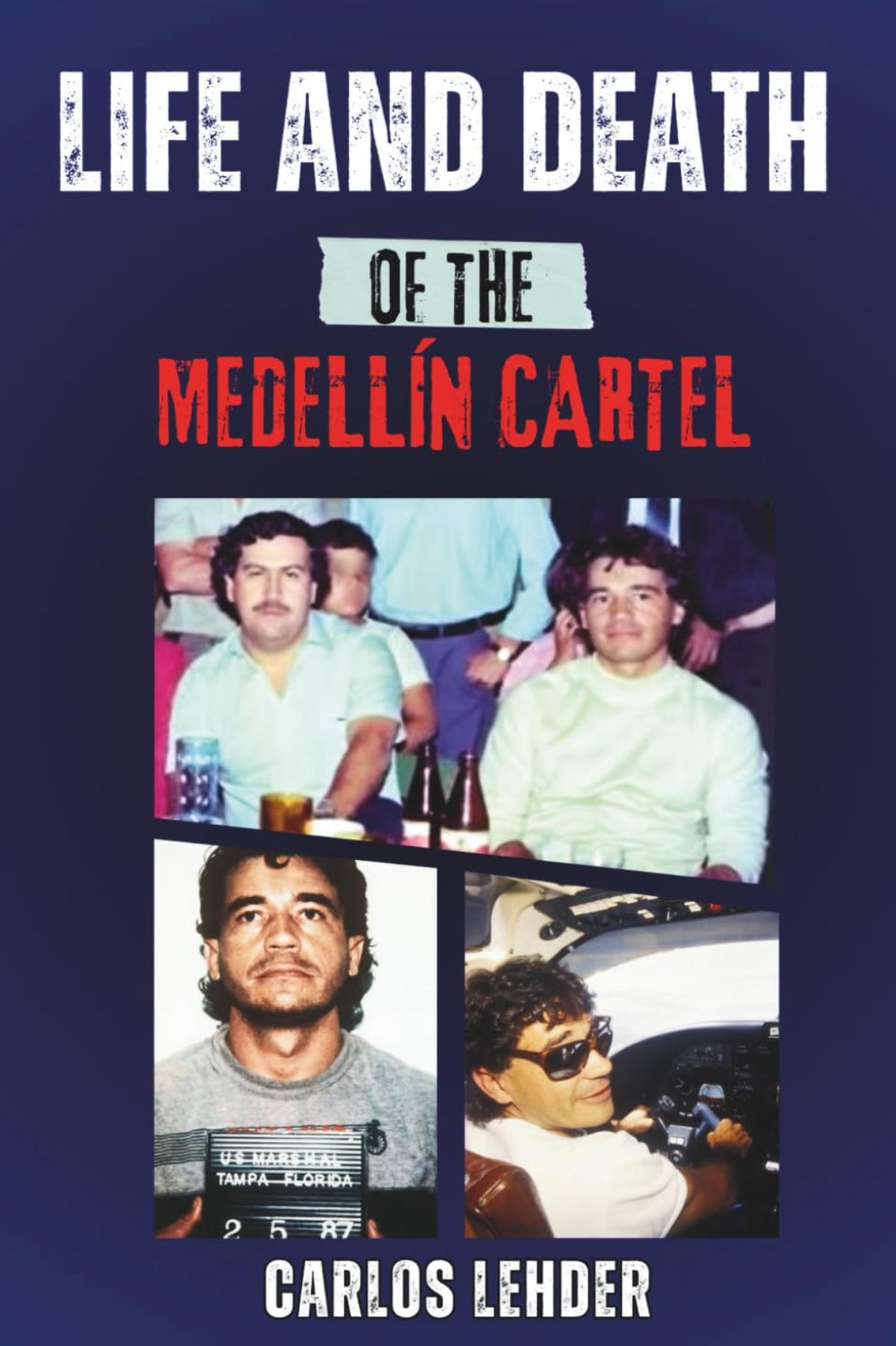

The son of a German father and Colombian mother, Lehder has been called “El Loco,” and described as a violent madman on cocaine, and as a Neo-Nazi narco; the Netflix series Narcos portrayed him with a big swastika tattoo on his arm. Yet the man I find is surprisingly gracious and polite, humbled by decades behind bars, including years in solitary confinement, and surviving cancer. He is slim, tanned and bright eyed into his eighth decade and speaks near perfect English after living in New York as a teenager and spending so much time behind American bars. He wrote about his exploits in a memoir, Life and Death of the Medellín Cartel, which recently came out in English, and you can find here.

Lehder doesn’t boast about reaching the dizzy heights of the trafficking game or want to talk about the crazy parties and beautiful women you see portrayed in the TV series, but he does concede his life was surreal. “Many humans use the one-liner, ‘Having your private island is like a dream.’ Well, I fulfilled that dream for real and unfortunately I did it illegally,” he says.

He is also aware that the United States now classifies drug traffickers as terrorists and that many in Colombia are still enraged about murders of family members by the Medellín Cartel in cocaine wars that drowned the country in blood. “It’s my testament, my will, my biography that I want to share with the American people,” he says. “At the same time, I want to apologize for my misbehavior when I was young and wild.”

The All American Drug

Lehder was born in 1949 in Colombia, where his German father worked as an engineer for a railroad company from 1927. His father didn’t fight in World War Two and was not interned like some other Germans in South America, but media outlets have reported that he was suspected of being a Nazi sympathizer. Either way, Lehder denies squarely that he himself was ever a Nazi.

“The truth is that I got absolutely nothing to do with the Nazis. When I was born, 1949, Germany was defeated, the Nazis were in jail, and many got killed. But I do have certain loyalties, number one, to my family. So I defend my father, who was never part of the German army,” he says. “In Netflix, they made a comedy about the cartel, and they placed me, and I see it with my own eyes, with the swastika on my arm. Well, that is reprehensible. That should have never happened.”

When Lehder was 15, he went to New York to pursue the American dream, not sneaking over the Rio Grande like many poor Latin Americans, but going on a plane with a visa and his mother buying the ticket. “In Colombia in those days, most of the people were farmers, and they looked at their sons as future farmers. I love farming, but that's not what I envisioned for my future. Therefore, I went to New York, the greatest city in the world, to learn.”

In the Big Apple, Lehder learned from the street and got into a gang of car thieves before doing his first stint in U.S. prison. American inmates didn’t bully him, however, but looked up to the Colombian who they hoped would get them cocaine contacts. Among them was a prisoner called George Young, who was serving a stint for flying marijuana in from Mexico and taught Lehder in the prison school. They would go into the cocaine business together; “Boston George” is played by Johnny Depp in the movie Blow where the Lehder character is called Diego.

Lehder first shifted cocaine from Bolivia to Colombia in a truck, before Colombia gained its place as the power house of South America’s blow production. He went on to buy cocaine for Lehder’s contacts when they flew to Colombia then began piloting planes loaded with powder himself and loved the thrill of flying.

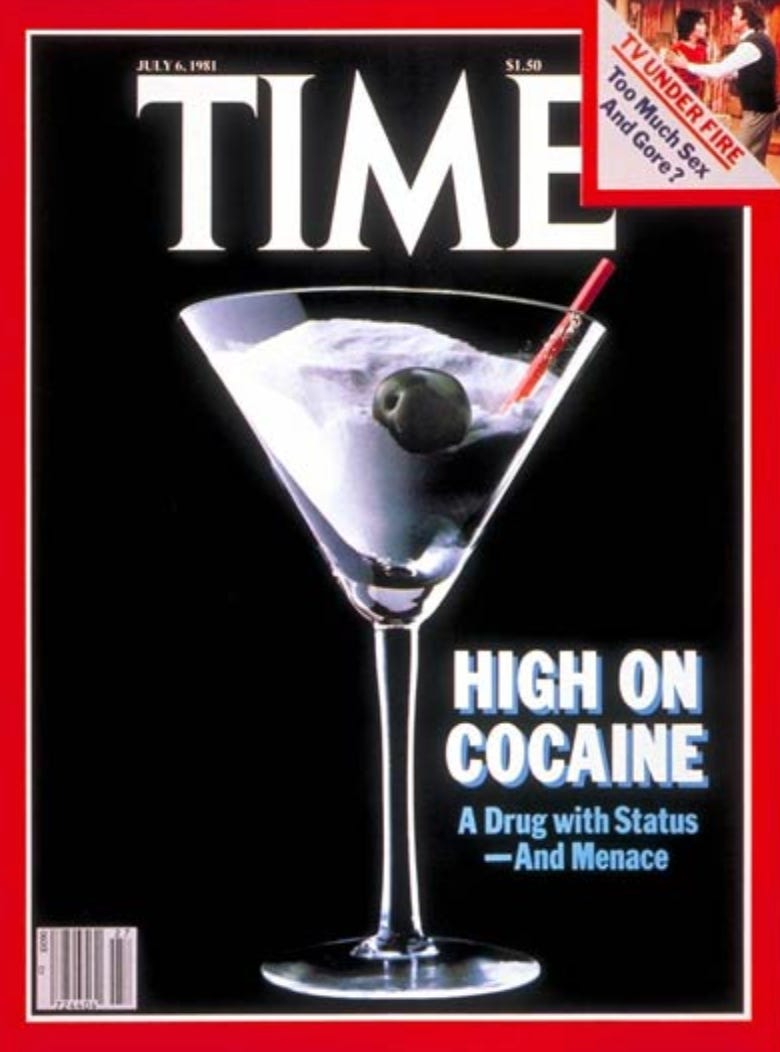

By the late seventies, U.S. demand for cocaine was soaring through the roof helped by a media portraying the drug as sexy and high status. In the 1977 movie Annie Hall, Woody Allen sneezes on a cigarette case of cocaine after a man tells him it costs $2,000 an ounce. Time Magazine had a 1981 cover with a picture of cocaine in a cocktail glass and called it the “All American drug,” as well as “A Drug with Status - and Menace.” The booming American market generated immense wealth for Lehder and his Colombian cohorts.

Lehder made his fortune by occupying the middle of the chain as a transporter, he explains. Thousands of small-scale Colombian narcos had contacts in cities all over the United States who could sell their cocaine to street dealers but they needed it smuggled in. Lehder delivered it for about $5,000 a kilo; he would be convicted of moving over 50 tons and it may have been a lot more.

To facilitate such a mammoth operation, Lehder took over Norman’s Cay and turned it into a trampoline for bouncing cocaine from Colombia to Florida. “Since I needed the airport to be functional and as discreet as possible, I hired a small company from Georgia that came in and built two big hangars, where I could put the airplanes and not be seen from the air… Then I brought in Colombian security. I brought in dogs for the security to walk around the island to persuade people not to come in.”

He had different ways of getting dope from the island to Florida, with his smugglers using small boats to avoid the coast guard or flying straight into private airfields. He paid Bahamian officials right up to the top. “I got plenty of information about their movements and I was able to perform until the day that the prime minister sent his attaché, his cadre, his assistant and told me, ‘Listen, you got 30 days to depart the Bahamas.’ ”

Colombian Cocaine Cartel

From the city of Medellín across a swathe of Colombia, 26 cocaine transport operations emerged, which they referred to as “offices,” Lehder says. While they worked together, they would also compete, especially to get good pilots, which were a valuable resource, “like a treasure.” It was the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), who came up with the name Medellín Cartel to describe this splattering of offices, Lehder says.

“We were never a homogeneous, unique, together, pyramidal organization with like a big chief in the top and hierarchies and like this guy commands everything,” Lehder says. “It wasn't like we call ourselves the Medellín Cartel and swore that we were Mafiosi. To the contrary. It was the American DEA that baptized, titled, and stamped a seal on us as the Medellín Cartel.”

Naming the cartel helped U.S. prosecutors make conspiracy cases against the narcos. Still, the Medellín traffickers formed a genuinely powerful network and had enough cash to build their own private armies. Decades later, narcos across Mexico call themselves cartels and even have military uniforms with their names and insignia.

Escobar built up his power base in the slums of Medellín, recruiting poor young men into a lethal force of sicarios, or hit men, while splashing out on schools, football stadiums and hospitals to gain a reputation as a benevolent godfather. With a distinctive crazed grin and thousand-yard stare around a trimmed mustache, Escobar became the iconic face of the Colombian narcos, a gangster as infamous as Al Capone.

“Pablo, at a very young age, was the chieftain of all the slums and ghettos of Medellín. So he grew up with them killing each other and robbing each other. Then he discovered cocaine and decided to be part of that,” Lehder says. “I remember he was a kind of unique individual in a sense that it was not pleasant to be near him. But when he came to business, he delivered. When he came to protect his people, he delivered. When he came to run his organization, he delivered. In the criminal world, he was the captain of a ship and he was very dangerous, and even his body language when he had the ability to study, analyze, and read the person you're dealing with.”

Having so much wealth made Medellín narcos a target for guerrilla groups in Colombia, a country that is harshly unequal and has swathes of mountainous jungles where insurgents can operate. Gunmen claiming to be guerrillas from the M-19, a revolutionary nationalist group, kidnapped Lehder for ransom and nearly killed him.

“I was shot right under my heart and I fainted because all this blood was pouring out,” Lehder says. “In their eyes, I was dying, and they didn't tie me up and that saved my life, because I woke up. It was a dirt road, so I can feel the jeep bouncing on the stones…I pushed the driver, the kidnapper. I jumped through the window to the road and then I ran and that was the end.”

In revenge for the kidnappings, the Medellín Cartel, led by Escobar, waged war against the M-19 and beat them until they made a truce. Later, the M-19 carried out a catastrophic attack on the Colombian Supreme Court in which more than 100 people died including a dozen judges, making it a painful episode in Colombian history almost akin to a Sept. 11. Escobar is accused of financing the guerillas to carry out that attack but Lehder denies he did.

“Although I despise Pablo in many ways, Pablo never, ever, had any dealings regarding the takeover of the Supreme Court of Colombia,” he says. “We, the narcos, never knew in advance that that was going to happen.”

The biggest guerilla group was the communist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia or FARC. While Medellín narcos would get into conflict with the FARC at times, they also worked with them to make money in the cocaine trade. To escape from the police, Lehder hid in the FARC’s territory in the jungle and they let him live while he paid the guerillas a 10-percent tax on his cocaine trafficking operation, he says. The FARC carried out massacres and kidnapped a lot of civilians for ransom, inflicting pain that Colombia is still recovering from.

The Colombian government came down on the Medellín Cartel by moving to extradite the bosses to the United States, where they wouldn’t be able to buy off prison guards. Escobar is famously reported to have said, “We prefer a grave in Colombia to a prison in the United States," and him and Lehder even formed political movements to fight extradition.

As political efforts failed, Escobar turned to violence and assassinated the Colombian minister of justice, Rodrigo Lara Bonilla. Lehder says he has nothing to do with that hit and that it put the traffickers in a vulnerable position. “If he was going to commit a crime, this is the most terrible thing he could have done for everybody, because it not only created a tremendous impact in society against all the narcos in Colombia, but also the minister was the symbol of justice. And he tried to assassinate that symbol.”

The security forces moved in on the traffickers and Escobar himself gave up Lehder’s location, he says. Colombian police arrested Lehder in 1987 and he was swiftly transferred to face trial in the United States.

From Prisoner To Witness

A court in Jacksonville, Florida, convicted Lehder in 1988 at the height of President Ronald Reagan’s war on drugs and as the crack cocaine epidemic tore through U.S. cities. Nancy Reagan even staged an anti-drug event in Jacksonville during the trial. The government locked Lehder up in what is known as a supermax penitentiary at Marion, Illinois, where he was held in solitary with almost no human contact. Such treatment is considered a form of torture in some countries and can drive inmates mad (which could be part of the objective). Lehder says he had to become his own psychologist to survive.

“I wrote down instructions to see if my brain will obey,” he says. “I would put, ‘I was born here in this prison. I live here all my life. I will die here? And my uniform is a very nice uniform. The guards, they are not my enemy. They are other inmates that go to sleep in the outside world and come back.’ And all these things trying to drive my brain a little bit away from the freedom planet and keep my mind in the dark planet.”

After four years, however, federal prosecutors gave Lehder a chance at life with an offer that he witness against General Noriega of Panama. Noriega was a key ally of the United States in Latin America, supporting its proxies in civil wars and working for the CIA. But he conspired with cocaine traffickers, oversaw a corrupt violent regime and may have been working with Cuba as well. After he fixed the election in 1989, the U.S. military invaded Panama and took Noriega home in handcuffs.

Before becoming a “snitch,” Lehder sent a message to Escobar to ask permission as he didn’t want to anger the drug lord into killing his entire family. Escobar told him he could go ahead, and Lehder took the stand as a star witness in 1991.

Although Lehder got his sentence reduced, he was still behind bars for 33 years until his release in 2020. He first went to Germany where he is also a citizen, but decided he wanted to live the end of life in his homeland of Colombia. I ask what he thinks about some young people idolizing the Medellín Cartel and how TV series can glamorize narcos.

“To the new generation, I say, ‘Stay away from getting involved in trafficking in cocaine,’ ” he says. “Do not do it. It's not worth it. It doesn't matter how much money there is. Sooner or later the law enforcement with all the technology will arrest the person, put them in prison. Or your own cadres, your own friends, your own partners, will rob you or eventually kill you. Trafficking in cocaine is the worst decision a person can make.”

Judging from how many youths still get involved in selling drugs and want to be the next kingpin, this seems a hard message to get through.

Photographs by Oliver Schmieg

Copyright Ioan Grillo and CrashOut Media 2025

Fantastic interview very interesting more than you are lead to believe. But it came from the man himself. Fantastic the way you let him just talk great interview & great interviewer credit where cridet is due what a person and to give you that interview was brilliant. He must have read about you great work and no was not a Nazi infact just loved John Lennon. Historic 🇬🇧💯

Presumably he had all his assets seized and no longer has access to any of the wealth he accumulated?

I’d be interested to know what his living conditions are like now. Is he living relatively comfortably, or reduced to some dingy hovel?