Mexico's Worst Narco Massacres

Mexico has suffered slaughters like war zones. How do we reckon with them?

Para leer en español click aquí.

Update on Dec. 11 with latest find in Jalisco and throughout.

Just 30 miles from the Texas border in the Mexican state of Coahuila lies a ranch that was the site of one of the worst extermination camps in the history of the Americas. In 2011, the Zetas cartel turned it into what they called a “kitchen” and dissolved mountains of corpses in acid. It was part of a massacre that claimed as many as 400 victims. Despite the insane scale of the bloodshed, the atrocity didn’t become widely known until three years later in 2014 and I visited that year.

It’s on a gray plain near the town of Allende, which is relatively prosperous from its border trade and beef. I found metal barrels still there along with plastic cans that had contained the industrial acids used for the melting of flesh. Police were digging up bones - skulls, ribs, vertebrae - but they were scattered and mixed up and it was hard to fit them together.

The fact such carnage went hidden for so long makes me shudder. I wonder if there are slaughters that have never been discovered. It makes me think of Seymour Hersh uncovering the My Lai massacre by U.S. soldiers in Vietnam. If Hersh hadn’t broken that story would we never know about it? Or is there a bigger force of nature that makes the truth come out?

Documenting the massacres in Mexico is not only for court cases - although the perpetrators commit offenses akin to war crimes. It’s crucial to understand what the hell happened to stop it repeating. And it’s key to Mexico’s historical memory.

A brave group of Mexican journalists and activists has taken up the task of seeking the truth, including Quinto Lab which mapped more than 2000 clandestine graves across Mexico. Reporter Juan Alberto Cedillo faced a tough challenge breaking the story of the Allende massacre. He learned in 2011 from his sources something unusually savage was taking place but didn’t have enough solid info.

“You knew there was something murky, something strong, but not the dimensions,” he tells me. “People didn’t want to speak. The Zetas were still there and they followed me wherever I went.”

It wasn’t until late 2012 that he published a piece in Proceso magazine, entitled “The Apocalypse in Coahuila” on how the Zetas had been hunting traitors and demolished 40 homes. Amid the rampant violence in Mexico, it went largely unnoticed.

Finally in 2014 after Cedillo covered a Zetas court case in Texas and the police were unearthing bones, he published that more than 300 people had disappeared. Writer Diego Enrique Osorno followed with a story in Vice and it was eventually picked up by ProPublica, and Netflix based the series “Somos” on it in 2021.

Cedillo has kept on the story, getting more testimonies and evidence to find what really happened. People were terrified for years but finally came forward. His decade of investigation has gone into a book, “The Massacre of Allende” which gives the most complete account.

He finds the death toll was even worse than feared. There are 285 confirmed murdered and a further 150 people unaccounted for. This could make it the bloodiest massacre in Mexico’s 19 year long cartels wars.

He also found Mexican military communiques about the disappearances and torching of homes from as early as March 2011. General Luis Cresencio Sandoval, who went onto head the entire army, was at the local military base.

“He knew in the moment about the massacre, he had all the information about it. The army was on the streets,” Cedillo says. “The massacre wasn’t known publicly because the officials never said anything…They kept it hidden because in some way they were complicit with the elite of the Zetas.”

Mass Shootings and Mass Graves

Massacre sites dot the map of Mexico like grim markers - Allende, San Fernando, Iguala, Cadereyta. There are shootings like in San Fernando in 2010 when the Zetas (again) gunned down 72 migrants. That might be Mexico’s biggest single execution of unarmed civilians since Pancho Villa killed 84 men in a mining town in 1915. But there are also mass graves that were filled with bodies over years, such as in Colinas de Santa Fe, Veracruz, where almost 300 skulls were found.

Cartel gunmen are believed to have carried out most of the slaughters albeit working with corrupt security forces. But the military and federal police have also carried out a series of massacres, and in turn police and soldiers have been the victims of mass killings.

The start date of Mexico’s modern drug war is largely considered December 2006 when President Felipe Calderón ordered a military crackdown on cartels. But the worst atrocities with victims of 40 plus were from 2010.

Most of Mexico’s half a million murder victims since 2006 have been killed as individuals or in small groups. Yet the massacres have a traumatic impact on the wider population. Some people stubbornly argue that Mexico’s cartel wars are just regular crime and violence but the mass killings are the clearest sign it has been an exceptional period of bloodshed.

Here is a timeline of some of the most lethal crimes since 2010:

2010, June - At least 55 bodies were found in a silver mine in Taxco, Guerrero, believed to be dumped by the Beltrán Leyva cartel.

2010, August - The Zetas shot dead 72 migrants from Central and South America in San Fernando, Tamaulipas.

2011, April to June - 193 bodies were found in a series of pits around San Fernando. Many were victims pulled off busses by the Zetas. Marcela Turati maps the oral history of this tragedy for a chilling book.

2011, August - Zetas gunmen burned down the Casino Royale in Monterrey while it was full of customers killing 52.

2011 to 2012 - In abandoned houses and plots in Durango, 383 corpses were dug up. They were believed to be victims of the Sinaloa Cartel stopping the incursion of the Zetas.

2012, May - The Zetas dumped 49 bodies on a highway near Cadereyta, Nuevo León. All were decapitated and had their hands and feet cut off.

2013 to 2014 - In La Barca, Jalisco close to the border with Michoacán state, 74 corpses were dug up, alleged victims of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel.

2014, February - News that hundreds were murdered and dissolved in acid in Allende finally came out. 285 victims have now been identified with another 150 disappeared.

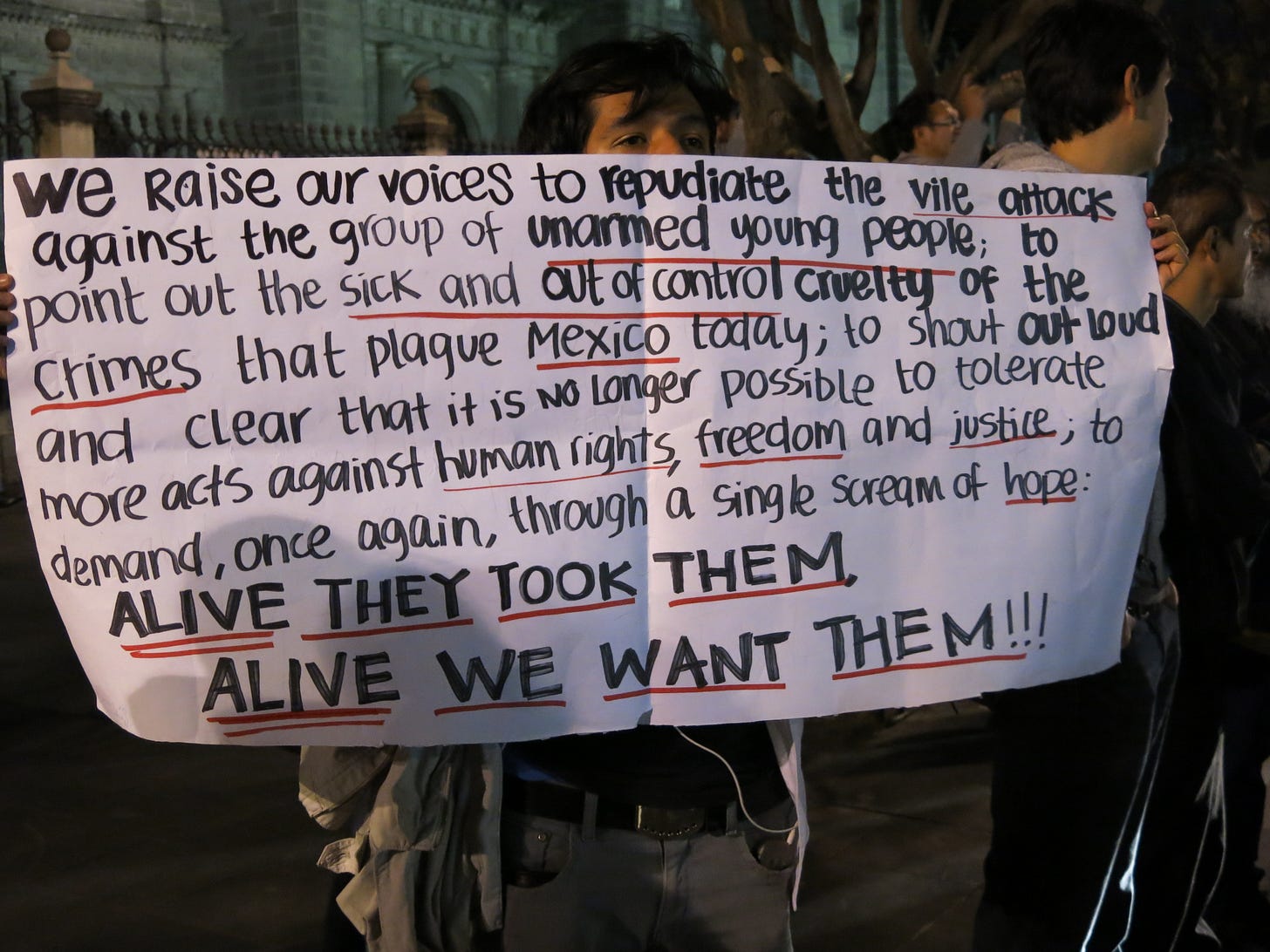

2014, September - In Iguala, Guerrero, 43 student teachers were disappeared. The crime was blamed on the Guerreros Unidos cartel working with local police, but soldiers are also accused of involvement amid an ongoing investigation.

2015, May - After a firefight between federal police and the Jalisco cartel, the police killed 42 alleged cartel members in what may have been a mass execution. The federal police had recently lost various officers to Jalisco cartel attacks.

2016 to 2019 - In Colinas de Santa Fe, Veracruz, a mass grave was dug up in cow fields with 298 craniums. The Zetas, Jalisco cartel and state police were said to use the site to dump bodies.

2020 - In El Salto, Jalisco, 113 bodies were dug up in mass graves, alleged victims of the Jalisco cartel.

2023 - In a series of graves discovered by the mothers of victims in Tlajomulco and Zapopan, Jalisco, 133 corpses were dug up, yet more victims of the Jalisco mob.

2025, March - A collective searching for the remains for victims locates a cartel training camp that ovens used to incinerate corpses in Teuchitlan, Jalisco. There are large numbers of shoes at the site and an unknown number of people were killed or disposed of there. It is alleged to belong to the Jalisco New Generation Cartel.

2025, Through the year - Collectives searching various mass graves in the Guadalajara metro area along with building workers dig up hundreds of bags with human remains. In one site, in an area known as the Agujas, they find 290 bags on a construction site.

Why Do They Do It?

It’s hard to make sense of how Mexico’s cartel wars became quite so destructive. In interviews I’ve done with sicarios, or hit men, they often speak of both how they became accustomed to killing on such a wide scale and how they removed a certain personal responsibility by saying they were following orders. A key factor was how cartels built paramilitary wings between the 1990s and 2000s .

The Zetas upped the game in the militarized violence as the founding members were Mexican special force soldiers who defected to the Gulf Cartel around 1998. Cedillo uncovered the army records of members, including Heriberto Lazcano, “The Executioner,” who built them into a fearsome fighting force. At least one Zeta, former infantry lieutenant Rogelio López, also trained at Fort Bragg in North Carolina, a 2009 U.S. diplomatic cable shows. The Zetas took anti-insurgency tactics and unleashed them on Mexico’s streets with no restraints, an army unhinged.

However, the leader believed to have ordered the massacre in Allende was never in the military. Miguel Treviño, or Z-40, was a car thief in Nuevo Laredo before he rose to the top of the Zetas. The way he unleashed the slaughter highlights the twisted logic of Mexico’s drug war.

When the Zetas pushed into the state of Coahuila, they got three local independent drug traffickers to work for them, Cedillo explains. The traffickers were moving large amounts of cocaine and marijuana through a network in Dallas. The DEA moved against the Dallas dealers and put pressure on the traffickers in Mexico, who gave up the Blackberry numbers of top Zetas. DEA agents shared the numbers with agents in Mexico who they believed were trustworthy, but who immediately told the Zeta bosses and they knew they had been betrayed.

Treviño sent an army of 200 sicarios into Coahuila to hunt for the traffickers but they managed to flee to the United States where they were taken into custody. The Zetas demolished houses and and rounded up people looking for them. When they realized they had fled it turned from a search to an act of revenge. The traffickers were wealthy and connected and had a lot of employees and family. Treviño, “wants to put the precedent that nobody is going betray him,” Cedillo says. “The revenge is going to be against the families, against the workers, and against friends in all the region.”

Another factor is that sicarios can be over zealous in performing the orders of their boss to make an impression. Or there can simply be confusion such as sicarios taking people for questioning and leaving them on a ranch where others find out they know nothing and then kill them. “It’s an irrational logic, with orders against orders that turns into a massacre without precedent,” Cedillo says.

Mexican marines arrested Treviño in 2013. He remained in prison in Mexico while he was also wanted in the United States for drug trafficking. However, when Cedillo pushed for his legal status, Mexican prosecutors said that Treviño was not even charged with the crimes of Allende. “It shows the madness and surrealism of this case.” In February, the Mexican military transferred him into U.S. custody as part of a mass expulsion of cartel operatives.

Searching for justice in Mexico’s drug war is a Herculean challenge. The biggest trials have been in the United States, including not only El Chapo but the former security minister Genaro García Luna. But U.S. prosecutors convict them for drugs not for the massacres south of the border.

Perhaps there needs to be a form of war crimes trials in Mexico for the atrocities of the last two decades. But that could be legally impossible and maybe the most violent players just need to put away and basic order restored. Either way, it’s crucial to simply tell the story of what happened. Horrific massacres of this scale should never remain as bloody secrets.

Copyright text Ioan Grillo and CrashOut Media 2023 / 2025

Photos Ioan Grillo / Juan Alberto Cedillo

This is more chilling than Stephen King. And you found those barrels! A disturbing and fascinating read.

At a tangent, you'll find this interesting - druggy Hitler and Germany WW2 heroin, cocaine, oxy and meth - https://www.npr.org/transcripts/518986612

The lawlessness and brutality of the cartels also filters down to small non-narco gangs that act with impunity due to the ineffective judicial system in Mexico.

These gangs kidnap, extort and murder knowing the possibility of getting caught is negligible. This is just another layer of criminal activity that goes mostly unnoticed because the cartels take precedent with the media and law enforcement.