Migrant Smugglers Enjoy Booming Business Amid Record Numbers

Mexico-U.S. border sees unprecedented detentions and crazy smuggling prices

I find the pollero, or human smuggler, outside the Bar Lucky Lady in Tijuana, a few blocks south of the U.S. border. He’s in his fifties, a seasoned operator, chubby with dark circles under his eyes. We start talking and he’s disappointed I am not a Russian or a Ukrainian wanting to go over the fence. “We have a lot of business. A lot of people want to cross right now,” he says. “But it’s hard. It’s not cheap.”

Prices are indeed booming, along with the demand. Sneaking in overland in a vehicle to a destination inside the United States costs $12,000 per person, he says. Going in a boat up the Pacific coast is at a whopping $18,000. There is also a cheaper method of just climbing over the fence to be picked up by the Border Patrol, after which refugees can attempt to claim asylum. For this, the “coyotes” are charging $500.

Costs of migrant smugglers can vary massively and I’ll get deeper into how tangled and disparate the business is. But his numbers fit into other accounts of how high fees can be right now.

“For migrant smuggling, $12,000 seems middle of the road, an average price. I have heard anywhere from $10,000 to $15,000,” says Alex Pacheco, a former Border Patrol supervisor, who carried out intelligence on cartels and human smuggling organizations. He said it can be substantially higher still for those from outside of the Americas, including from China, Russia, and India. Another smuggler spoke to Telemundo and said the cost to travel in boats was $15,000 to $20,000.

These surging prices come as the U.S. border patrol has made a record number of detentions of people crossing in from Mexico without papers. For the fiscal year of 2022, which ended Sept. 30, agents had more than two million “encounters” for the first time ever on the southwest border. This throws oil on the fire of an issue that burns at the heart of partisan politics in the run up to the U.S. midterm elections.

With these unprecedented numbers, and sky-high prices, business is booming for the smuggling networks in Mexico. This not only means more money for the ruthless operatives behind tragedies such as the 53 people who suffocated and sweated to death in a tractor trailer in San Antonio in June. (This year breaks records for the number of migrant deaths on the border too at more than 700). But the smugglers also work for, or pay money to, the same crime bosses that traffic drugs and guns and unleash relentless bloodshed here.

“The mom and pop polleros no longer exist. It’s all organized crime,” says Pacheco. “If you go through any region on the border, you have to pay plaza. If you run prostitution, if you run alien smuggling, if you run drugs, if you are bringing weapons across, if you are doing maritime, you have to play plaza.” The word “plaza” refers to the turf, and to paying the gangsters who control it.

There are no balance sheets and tax records on the human smuggling industry and it is impossible to know its exact profits. But even multiplying low estimates of the number of people paying money to smugglers with low estimates of the fees and you get into billions of dollars. In December, Mexico’s Foreign Secretary Marcelo Ebrard said the human smuggling networks could be making $14 billion. And that was before the record this year.

When mobs such as the Jalisco New Generation Cartel and Sinaloa Cartel war over territories, they are fighting over this enormous migrant bounty as well as the drug routes. And their violence in turn causes more people to flee for their lives, adding to the river of refugees heading northward.

The Bloody Evolution of Migrant Smuggling

For a documentary on music, I got in touch with “Chaparro,” who was a migrant smuggler in Tijuana back in the early 1980s. Chaparro worked with Chalino Sánchez, who would go onto become the famous corrido singer, and with his brother Armando, who was shot dead in Tijuana by another smuggler in 1981 – the subject of one of Chalino’s ballads.

Chaparro and Armando used to drive the migrants over through a Tijuana neighborhood called Libertad. At the beginning, they charged $200 per head, Chaparro tells me.

Migrant smugglers are known as coyotes, the wild canines that roam the desert, or polleros, meaning those who herd chickens. (The migrants themselves are the chickens, the merchandise). Many polleros, including Chaparro, were from country villages and so the farm labels came naturally. They were independent operators and there were no cartels back in those days, although Chaparro said they paid bribes to local police.

As the decades went by, the prices for polleros went up exponentially to the five digits today. They rose through Democrat and Republican administrations, through the 9-11 terrorist attacks to the mass deportations under President Barack Obama, to the calls by Trump to “Build a Wall,” to the current rush as the Covid pandemic eases off.

A core problem is that the more the United States beefs up enforcement at the border, the more polleros can hike their prices, in turn growing their networks and power. And the economic leveling out promised by NAFTA never happened. While the U.S federal minimum wage drags at $7.25 an hour, it is $8.50 for an entire day in Mexico and under $25 for a whole month in Venezuela. Violence and crime also plagues swathes of Latin America, driving people from their homes to seek refuge in El Norte.

There have been gluts when migrants want to come less, such as in the 2008 recession or during the pandemic. But there has been much more demand, including now under President Joe Biden who is overseeing a profound labor shortage.

Drug traffickers in Mexico became more heavily armed and ruthless in the 2000s, and they diversified into a portfolio of rackets from stealing oil from pipelines to wildcat mining. In practice, this often meant shaking down the criminals already doing these activities. Human smuggling was a no-brainer as the cartels had long claimed and fought for territories along the border.

As the polleros became more entwined with the cartels, they went from local hustlers to cogs in sophisticated networks. “They got better in so far as being creative with fence compromises, ladders, vehicles outfitted with ramps to drive over the border fence, cloned vehicles,” Pacheco says. “They would clone construction trucks and we wouldn’t even know what they were.”

The networks also grew through southern Mexico and into Central America and beyond. In the late 2000s, the Zetas cartel carried out mass kidnappings of thousands of Central American migrants traveling through Mexico, getting their relatives in the United States to wire money for their release. This cumulated in the horrific massacre of 72 migrants in San Fernando in 2010. However, coyotes in Central America began working with the cartels and negotiating payments for the safe passage of migrants through their turfs.

In 2014, I talked to a coyote in the Honduran city of Choluma who was taking migrants from his homeland and working with the Gulf Cartel to move them into Texas. Back then, they charged $6,500 per trip, giving migrants a second chance if they were caught on the first attempt.

I call Honduran journalist Orlin Castro to ask about the current prices. He tells me they charge $14,500 to go from Honduras into a destination in the United States by vehicle. They have a cheaper package of $11,500 that involves walking over the desert, which is where many of the deaths occur, especially with the heatwave. And they have a new package at $6,000 for what they call a “viaje de entrega,” in which they take people into U.S. territory to hand themselves in with the hope of gaining asylum.

The Dream of Refuge

The rise in asylum claims is a huge factor driving the current surge. When Customs and Border Patrol announced the record-breaking numbers, it said in a release: “Failing communist regimes in Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba are driving a new wave of migration across the Western Hemisphere.”

It’s a complex issue and I have a separate piece on this coming. But there is no doubt that the amount of asylum seekers has increased hugely, and includes both those fleeing authoritarian governments such as that of Venezuela and those fleeing gang violence in countries such as Honduras. (Some flee both as criminals and government agents can be the same).

Asylum seekers shouldn’t need to pay smugglers as they are applying to enter legally. However, the system has got massively backed up and has got very confusing amid changes made under Trump and then under Biden, which have got tangled up in court rulings. Trump controversially made asylum seekers wait in Mexico, which led to swelling refugee camps, an action that should no longer be taking place.

His administration also introduced “Title 42,” in which migrants can be immediately expelled for health reasons because of the pandemic, a measure that is still being used. (This means some of those detained by the border patrol can be ejected into Mexico and then quickly try to enter again. However, this has long been the case among Mexican nationals and was common during the high point of Mexican migration in the mid 2000s).

In practice, it is currently confusing and difficult to turn up at the official crossing and claim asylum. At a shelter in Tijuana, I find José Luis Aguilar (pictured below), a 27-year old who fled San Salvador with his family after being shot by gang members. He is keen to apply for asylum legally and doesn’t want to go over the wall but is unsure about how to do it and the shelter organizers have stopped giving out information.

Many asylum seekers instead cross undocumented into U.S. territory and hand themselves in. On the San Diego side, I see dozens sat waiting in a buffer zone between two U.S. fences. The migrants want to go into custody but the agent tells me that the center is already full and they have to wait to be processed.

Venezuelan journalist Jorge Benezra explains to me how a lot of the refugees currently arriving at the U.S. border had previously fled hunger in Venezuela and were living in poverty in surrounding countries. They don’t have the fees that polleros ask for but head north in their own groups with a few thousand dollars to pay what they have to.

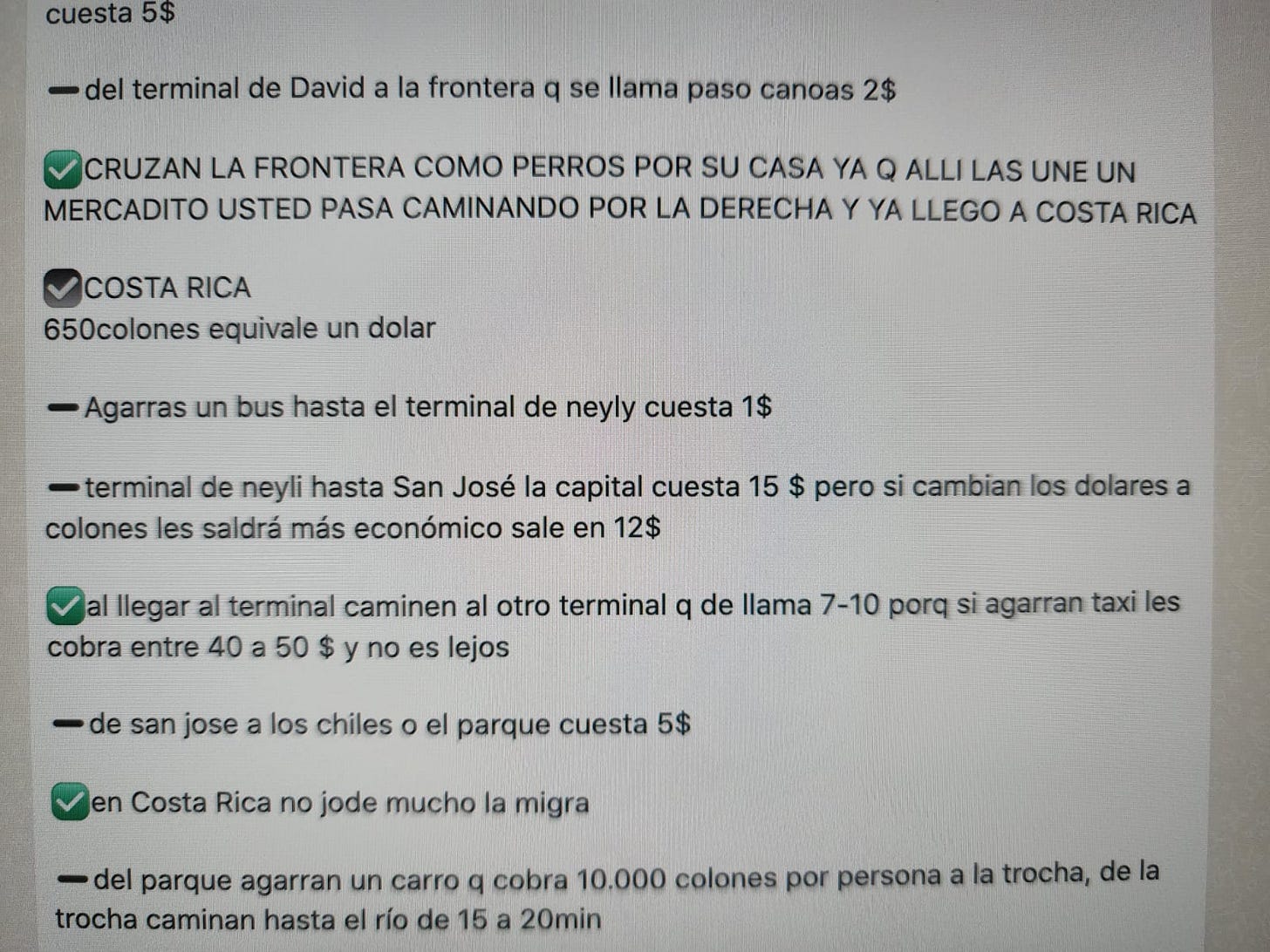

Benezra acquired a Whatsapp message (pictured below) that refugees pass around with instructions on how to head through Central America to the United States, along with the amounts they have to pay along the way. “Head over the border like dogs in your home,” it describes on crossing from Panama. “In Costa Rica, the ‘migra’ don’t fuck with you too much.”

When jumping over the fence or floating over the river in a tire into the United States, the cartels demand money from migrants whether they want the help or not. Many will cough up fees such as the $500 the pollero cited to me. Others will risk it.

At the shelter in Tijuana, I meet Claudia Aguilar, 33, who fled her home in Honduras with her husband and 17 year old daughter. They attempted to cross the Rio Grande at Piedras Negras which is over the river from Eagle Pass. But they were chased by armed men and forced to split up. She initially lost track of her daughter and was terrified, but she later got in touch with her by telephone to confirm she made it into Texas.

There also continued cases of mass kidnappings of asylum seekers or migrants who don’t pay for their passage through cartel territories. Gunmen hold groups in houses or ranches often torturing them and send videos to family members to get thousands of dollars. Sometimes, migrants pay a crooked coyote who also hands them into these kidnappers.

“Human smugglers are just as bad as drug traffickers because they treat human beings like merchandise. They don’t look at them as people,” Pacheco says. “You abandon 500 kilos in the desert. No big deal, right? You abandon 500 people. You are a murderer.”

In the current environment, these groups appear bigger and richer than ever.

All Photos by Ioan Grillo.

Copyright Ioan Grillo and CrashOut Media 2022

Thank you, I enjoy reading you very much.

sup mr grillo, substack is pretty cool