On Gringo-fication and Gringo-phobia

Reflections on the anti-gringo marches in Mexico City

Para leer en español click aqui.

I.

I got off a plane from London to Mexico City in the year 2000, with a backpack, a one-way ticket and dream of being a journalist. That night, I found my way to the Plaza de la Revolución and walked into a taco restaurant and almost had a heart attack when I saw the prices. I thought the symbol of “$” stood for dollars and I didn’t realize they used that same symbol for pesos. A taco costs ten fucking dollars, I thought. This must be where Mexico’s super-rich eat.

I wandered out worried into the plaza and saw a torta stand that just had the number 20 and I thought this must be the street peso economy. The guy made me a torta cubana, the first thing I ate in Mexico, and I loved it. I’ve been munching delicious fare here in the 25 years since.

I soon got my first journalism job at The News, an English language newspaper published by Novedades Editores, with a proper old school newsroom on the corner of Balderas and Morelos. They paid me under 7,000 pesos a month back when it was ten pesos to the dollar, so the princely sum of about 170 bucks a week. But I could get by on the salary because things were cheap.

I shared an apartment in Narvarte with a fellow wannabe journalist (a Marylander) and we paid 1,500 pesos ($150) a month each for decent rooms. Our favorite spot of El Kalimán in La Condesa served up tacos de pastor for three pesos (30 cents) a pop. A stand outside the newsroom sold a half-liter of freshly-squeezed orange juice for five pesos (50 cents). A cantina bunged us a bucket of six beers for 50 pesos (five dollars).

I had the time of my life. Mexico City was exotic, chaotic, soulful, fascinating, edgy, dysfunctional, surreal, happening, and, to use a cliché, magical. And there weren’t too many of us gueros, or blonde foreigners. We stood out and people asked, where are you from, followed by the compulsory question, “Y te gusta México?” - “Do you like Mexico?”

“Yes, sure I like it that is why I’m here,” I would say. But I more than liked it. I fell in love with Mexico.

II.

The word gringo means different things in different countries. In Brazil, it means any foreigner whether French, Guatemalan, or even Congolese. In Mexico, it means someone specifically from the United States, particularly Anglo but also black or Asian American (although there are distinct words for Mexican Americans like pochos).

If someone in Mexico refers to me as a gringo casually in conversation it doesn’t bother me, although I might say, “actually I’m from Inglaterra.” But if someone says it in a hostile tone, I’ll react accordingly.

The number of foreigners including Canadians, Europeans but especially gringos swelled in a few trendy Mexico City neighborhoods, Condesa, Roma, Polanco, during and after the pandemic. People came for more freedom, cheaper bills, parties, and the edgy soulful city I had discovered two decades earlier. Remote working was now a thing so people could do graphic design or coding from a Condesa apartment for a company in New York. Bloggers offered advice on how to make it happen.

A foreign guero, or a black American, is no longer a rare sight and you see restaurants packed with English speakers. People react distinctly to a crowd of outsiders than to an individual.

Prices surged in Mexico City. There are various forces behind this like broader hikes after Covid and property inflation that richer countries had two decades earlier. But in certain neighborhoods the foreigners undoubtedly push costs, especially for restaurants and rent.

A single room can go for over a thousand dollars a month, which is cheaper than Brooklyn but inhibitively expensive for most Mexicans. Property owners can make more renting per night on Airbnb. Investors and speculators get in on the profits. Residents who had let for decades, some running torta stands or selling pozole (stew), have been forced to move to poorer barrios.

Meanwhile, Trump’s threats of tariffs and ICE migrant raids provoked anger in Mexico that was deflected on gringos here. In February, the singer León Larregui unleashed a series of irate tweets including one saying: “Visas and equivalent deportations for the gringo parasites that live in Mexico.”

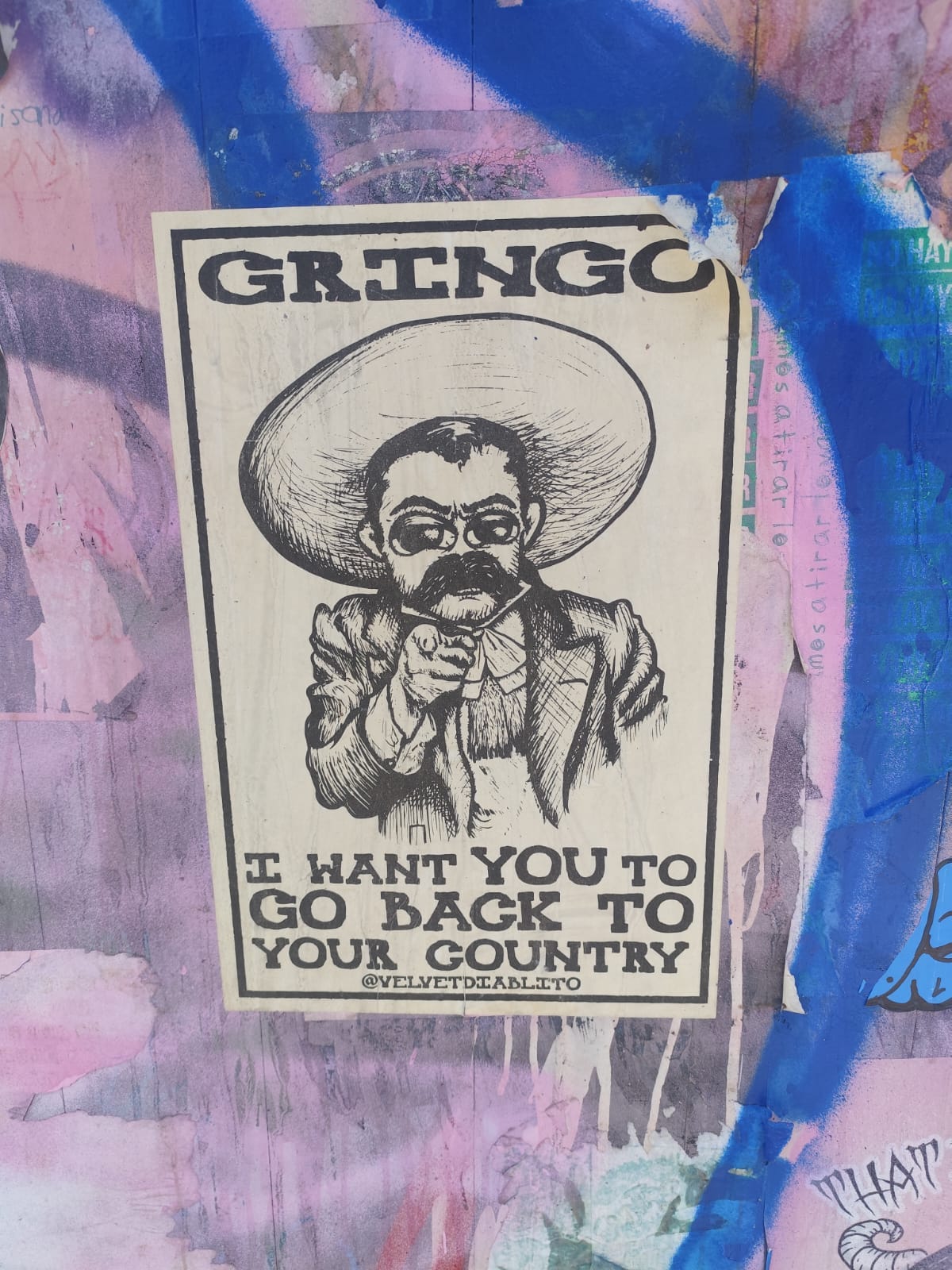

This July, protesters went on three demonstrations against gentrification that were aimed especially at gringos, or what we might call “gringo-fication.” About a thousand people marched each time through neighborhoods like the Condesa, including anti-gentrification activists and some forced out by rent hikes as well as students, anarchists and punks.

Protesters called for rent freezes, for digital nomads to pay taxes and for gringos to go. Yet they not only complained of the economic impact but of an imposition of a foreign culture, of not appreciating Mexican food and music and not speaking Spanish. A repeated claim is that restaurants in the Condesa have reduced their level of spicy chili for the gringos (the ultimate slap to Mexican culture, if indeed true!).

On July 4th, coinciding with U.S. Independence Day, protesters smashed the windows of some Condesa businesses, including a Starbucks and high-end taco spot, El Califa, yelled at customers sitting outside restaurants and sprayed walls. The biggest chant was “fuera gringos, fuera gringos,” or “gringos out, gringos out.”

Signs included: “Death to the neo-colonizer”; “Gringo: stop stealing our home” ; “Ex-pat = gentrifier” and even “Hagan pozole de gringo” or “Make a gringo stew.” A protester burned an inflatable effigy of Donald Trump.

III.

Many Mexicans condemned the xenophobia, with a lot of newspaper pieces lamenting it. President Claudia Sheinbaum, whose Morena party espouses a leftist-nationalist rhetoric, also slammed it. “The xenophobic signs of this protest should be condemned,” she said. “Even for a legitimate demand, like that about gentrification, you cannot call for a nationality out of the country. Mexico has always shown solidarity, fraternity.”

Sheinbaum was referring to the communities of foreigners that have been absorbed into Mexico over the last century including refugees from Franco’s Spain. Sheinbaum herself is the descendant of Ashkenazi Jews who fled Nazi-occupied Europe. And the Mexican “race,” dubbed the “raza cósmica” by intellectual José Vasconcelos, is itself a fusion of the indigenous and Spanish, albeit after bloody conquest.

However, I know various people in Mexico who privately echo the same complaints as the protesters. The gringos are pushing prices up, they say. They don’t respect Mexican culture. And the real clincher: they are making restaurants reduce the amount of chili.

Social media is nuts and best not to take too seriously. But there are mountains of videos and comments complaining about gringos and foreigners in Mexico. The media posters decry that gringos arrogantly call themselves “expats” and say they want to colonize. They order Mexicans about. And they don’t even like loud Mexican music (there have been a few real examples of this).

Online xenophobia in Mexico is similar to a lot of countries, including the United States. Yet some also dress it up in left-wing rhetoric. To be anti-gringo is to be against the empire. Mexican nationalism is now probably stronger on the left than the right.

My friend Andrew Paxman, another dastardly Brit in Mexico and historian at the CIDE institute, has written about anti-gringo sentiment (or gringo-phobia!) going back almost two centuries. It took root with the 1846 Mexican-American war and the United States seizing huge swathes of territory, including Texas, Arizona and California. It became more virulent during the Mexican Revolution from 1910, when revolutionaries seized land from gringo owners and U.S. troops made another incursion into Mexico.

“There is an idea of defending the fatherland against the white protestant barbarians,” Paxman says. “There is a sense that Americans are religiously suspect and voracious, land grabbing.”

This anti-gringoism, Paxman explains, can be seen in murals, in Mexican movies of the golden era, and heard in corridos. He also points to the Uruguayan writer José Enrique Rodó, who was popular in Mexico and wrote how Latin Americans are spiritual and artistic while gringos are shallow and materialistic. This notion is echoed by the protesters in Condesa.

Yet while anti-gringo sentiment exists, actions on the ground tell a different story. More than 11 million Mexicans and another 26 million Mexican Americans live in the United States. Large communities of U.S. retirees have resided in towns such as San Miguel de Allende for decades. Actual xenophobic violence is rare. Gringos in Mexico haven’t freaked out about the protests because they don’t take them too seriously and their daily experience is generally good.

IV.

My personal experience in Mexico over 25 years has been overwhelmingly positive and I’ve grown so close to people that I don’t think about the nationality difference most the time.

Foreigners can also benefit from a phenomenon known as malinchismo, named after La Malinche, the lover and translator of conqueror Hernán Cortés. The idea is that a Mexican may favor the foreigner over the indigenous like Malinche did.

Yet malinchismo can flip fast to xenophobia. When I’ve had arguments over a bad tackle playing football or a fender-bender in a car, people are quick to say, “do that shit in your own country.” One time I was drunk in a cantina and a guy asked if I was a fucking gringo. When I said I was British, he said it was the same shit and wanted to fight. I was so shit-faced I could hardly stand and told him to bring it on but the bar security piled in. These incidents don’t grind on me though as most people are nice most the time.

In the decades I’ve been in Mexico, the United Kingdom has seen the biggest influx of people since the arrival of Germanic tribes in the middle ages. They come from every country on the planet but the top source nations in 2024 were India, Nigeria, Pakistan and China.

The question of immigration and identity has shot to the heart of British politics and sparked a pained national debate. If an election were held today then the party Reform UK would be predicted to win on an anti-immigration platform. Protests are currently sweeping hotels housing asylum seekers across the country. Last summer there were riots when the son of Rwandan migrants stabbed three girls to death at a Taylor Swift-themed dance workshop.

The unrest in Britain against foreigners (especially asylum seekers) is far more serious than the protests in Mexico against gringo-fication. But then the transformation of London is on a different level from that of Mexico City.

While gringos are obvious in the Condesa, foreigners likely make up just 1 percent of the population of Mexico City. In London, the foreign-born are about 40 percent. Furthermore, the number of Londoners identifying as “white British” tumbled from 71 percent in 2001 to just 36 percent in 2021. Such change in Mexico City would be hard to imagine.

Mexico’s anti-gringo protests are more akin to protests in Spain against tourism. Barcelona residents also complain about Airbnb prices forcing them out their neighborhoods and spray tourists with water pistols. This summer there has been a heatwave in Spain so getting sprayed with water would be quite refreshing.

V.

Globalization became a catch-phrase in the nineties to describe the free movement of goods, services, capital and people. It was more of a right-wing concept associated with the neoliberal economic project, the idea the globe is one big market place.

On the left, a small but significant number argue for open borders, with the idea that immigration is a human right and everyone should go wherever they want. A larger part of the left are not explicitly open borders but very pro-immigration.

Whatever the ideology, cheap travel, remote working, and smuggling networks all added to the mass movement of human beings. Yet the flows from immigration, refugees, tourism and digital nomads are hitting a speed bump. Nationalist parties and protests gain ground from Mexico City to Berlin. Trump’s victory in 2024 owes a large part to anger over the record number crossing the southern border.

This issue is so emotive as it gets to the core of who our tribe is and what its territory is. In today’s confusing world, a lot of us hold contradictory positions. Many Americans don’t want illegal migrants but U.S. businesses like undocumented labor. Protesters want to deport gringos in Condesa but are against deporting Mexicans from Los Angeles. Brits living abroad can be against immigration back home. And Mexican Americans can lament too many gringos in their ancestral homeland.

I have mixed feelings about this tapestry. A level of immigration is enriching yet globalism is clearly not a win-win for all. I think there should be measures to stop people getting priced out of their neighborhoods but I don’t know exactly what they are. I respect national cultures and think they make the world a richer place. If you move to a different country, I strongly advise speaking the language and embracing the culture - and not moaning about loud banda music! Yet xenophobia is an ugly dangerous force that has led to some of the most horrific violence humans have known.

A quarter of a century after I stumbled out of a plane to a torta stand in Plaza Revolución I am still here in this beautiful crazy urban sprawl of 20 million people. The price of tacos has gone up but millions are still eating them every day from the grimiest stand in Iztapalapa to the plushest restaurant in Polanco. And if you look, you can definitely still find spicy sauces stuffed with habanero chili that you will feel through your face and throat. Mexico is still Mexico.

Photos by Ioan Grillo 2024 to 2025

Copyright Ioan Grillo and CrashOut Media 2025

Thanks for writing about this. I saw the headlines and wondered how much of a story it was. Getting priced out of your neighborhood crosses culture. When I lived in Colorado the complaint was that Vail, Aspen, Steamboat Springs had been priced out of reach for the “natives”. The most popular tshirt for awhile read “If God wanted Texans to ski, he would have made bullshit white”. Great post.

You're speaking to the heart of what is so thorny about all of this. And like you, I find there are few crowd-pleasing solutions. Mexico is a magical place, so wild it feels like freedom from a firehose. It needs to stay that way.