What is the AMLO Security Doctrine?

Was “hugs not bullets” just a cover for militarization?

There are two phrases that sum up the security policy of Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador: “Hugs Not Bullets,” and “National Guard.”

The silver-haired 68 year old known as AMLO, who defines himself as a leftist, began using the term “hugs not bullets” or “abrazos no balazos” more than a decade ago but he popularized it in his triumphant 2018 election campaign. It is a clever slogan in being catchy and portraying the idea of both peace and social solidarity. Along with it, AMLO promised an end to the devastating drug war that has claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of Mexicans, and a moratorium on the massacres by police and soldiers.

The phrase is also the subject of endless memes. Critics slam it as showing weakness in the face of ultra-violent gangsters, and they say it alludes to corruption, hugging the narcos because they pay bribes. These critics come from many corners, but being “tough on crime” is often linked to the right.

AMLO also talked in his campaign about creating a new force called La Guardia Nacional, or National Guard, although it initially got little traction in the press. When he secured the constitutional changes in March 2019, he championed it as a novel agency driven by fresh recruits. They would be like United Nations peace keepers, he said, and help get the army off the streets.

The pretense of the Guardia being independent from the army finally came to an end this September when AMLO signed a law handing over its command to the generals. The force was already under effective army control and more than three quarters of the guards were soldiers or marines in a new uniform.

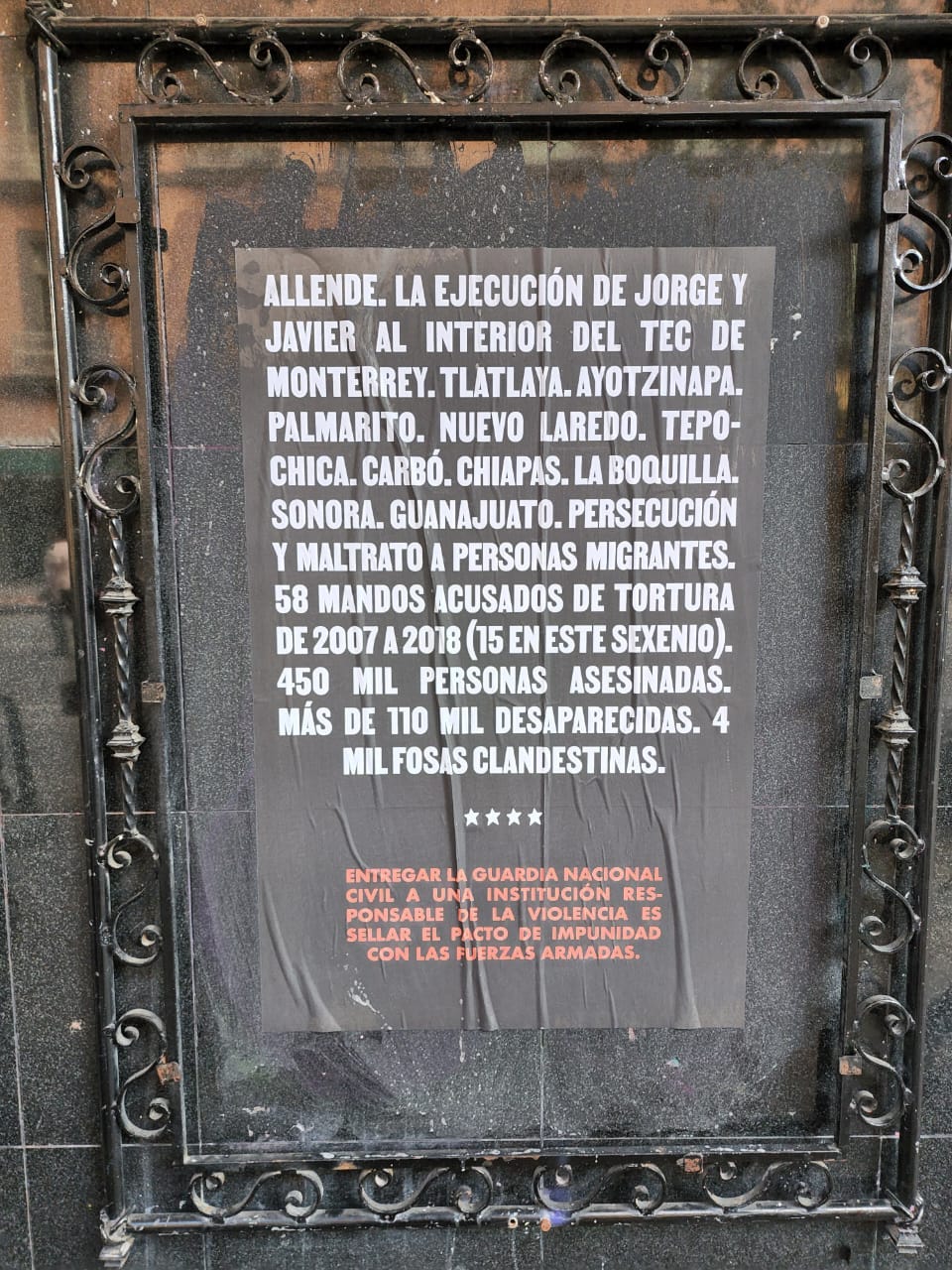

Critics warn that AMLO has not only found a way to keep troops on the streets for the foreseeable future. He has also given immense power to the army brass in a region with a history of coups and dictatorships. Again, these critics come from many corners, but anti-militarization has a long history on the left.

Holding these contrasting positions of “abrazos” and “Guardia” can seem contradictory to the point of being Orwellian, a doublethink to declare both at once. Amid this, some claim that “abrazos” was just a lie and AMLO was plotting the military buildup all along.

“I think this was the plan,” says Alejandro Hope, a security analyst who used to work for Mexico’s federal intelligence agency. “My guess is that his anti-militaristic rants were more of a tactical shift…It’s just a slogan. There are no abrazos.”

It is always hard to figure out what is in a politician’s head. But I personally think that AMLO had less of a clear idea of what he was going to do about the drug war. His position evolved over time, steered by policy failures and the brutal reality on the ground. He genuinely believed he could bring peace to his scarred nation, while also wanting to restore the weakening power of the Mexican state. The tragedy is that what has become the “AMLO Security Doctrine” has failed to quell the cartel bloodshed, while setting up another challenge – of a military-industrial complex - that could have grave consequences in the future.

The Winding Road to Militarization

The son of shopkeepers from a small town in the swampy state of Tabasco, AMLO vied for the presidency for two decades, first as mayor of Mexico City and then as an unsuccessful candidate in two elections, before his victory in 2018. Back in 2005, I met him along with a group of foreign journalists. Asked about police corruption, he replied: “There is one institution we can trust – the army.”

His belief in the militia runs deep. Despite a history of army atrocities in states such as Guerrero and Sinaloa, there is strong faith in the military in much of Mexico, including in AMLO’s home of Tabasco, a bountiful source of recruits.

“He really sees the army as the army sees itself,” Hope tells me. “As the people in arms. As a pueblo uniformado. As an inheritor of the Revolution. As a tool for social advancement.”

However, AMLO didn’t focus much on law enforcement during his first presidential run. His main thrust was to rail against a corrupt elite who he calls “the mafia of power,” which hordes the nation’s wealth and keeps the poor down. It is a critique that has merit. But AMLO lost to the socially-conservative Felipe Calderón in the closest election in Mexico’s history.

President Calderón launched his military offensive against drug cartels in December 2006, and it would see more than 100,000 soldiers, marines and federal police hit the streets. Calderón dressed in army uniform and announced “no truce or quarter for the enemies of Mexico.” The troops made record seizures and bought down kingpins in fierce gun battles while detained hit men gave shaky confessions on news bulletins.

Calderón’s offensive led to an explosion of bloodshed - murders doubled between 2007 and 2010 – and the killing has been ravaging the country since. The violence is complicated and has various causes. But it is driven by the organized crime networks, which not only traffic drugs but engage in a portfolio of rackets from human smuggling to oil theft, and are entwined with corrupt officials. Under Calderón, a government unit determined that organized crime and the security forces fighting it accounted for three quarters of homicides.

When AMLO ran for the presidency in 2012, though, he did not make this drug war a core issue, sticking to his key line about fighting the mafia of power. In the presidential debates, there was little of substance said about crime and soldiers and the headline was of a busty playboy model who handed out the questions.

Enrique Peña Nieto, a polished candidate with a soap-opera star wife ran for the Institutional Revolutionary Party or PRI, which had controlled Mexico for most of the twentieth century. Peña Nieto didn’t talk much about the drug war either but he subtly promised to “bring back order and freedom,” implying that things had been better under the old PRI. He beat AMLO by 6 points.

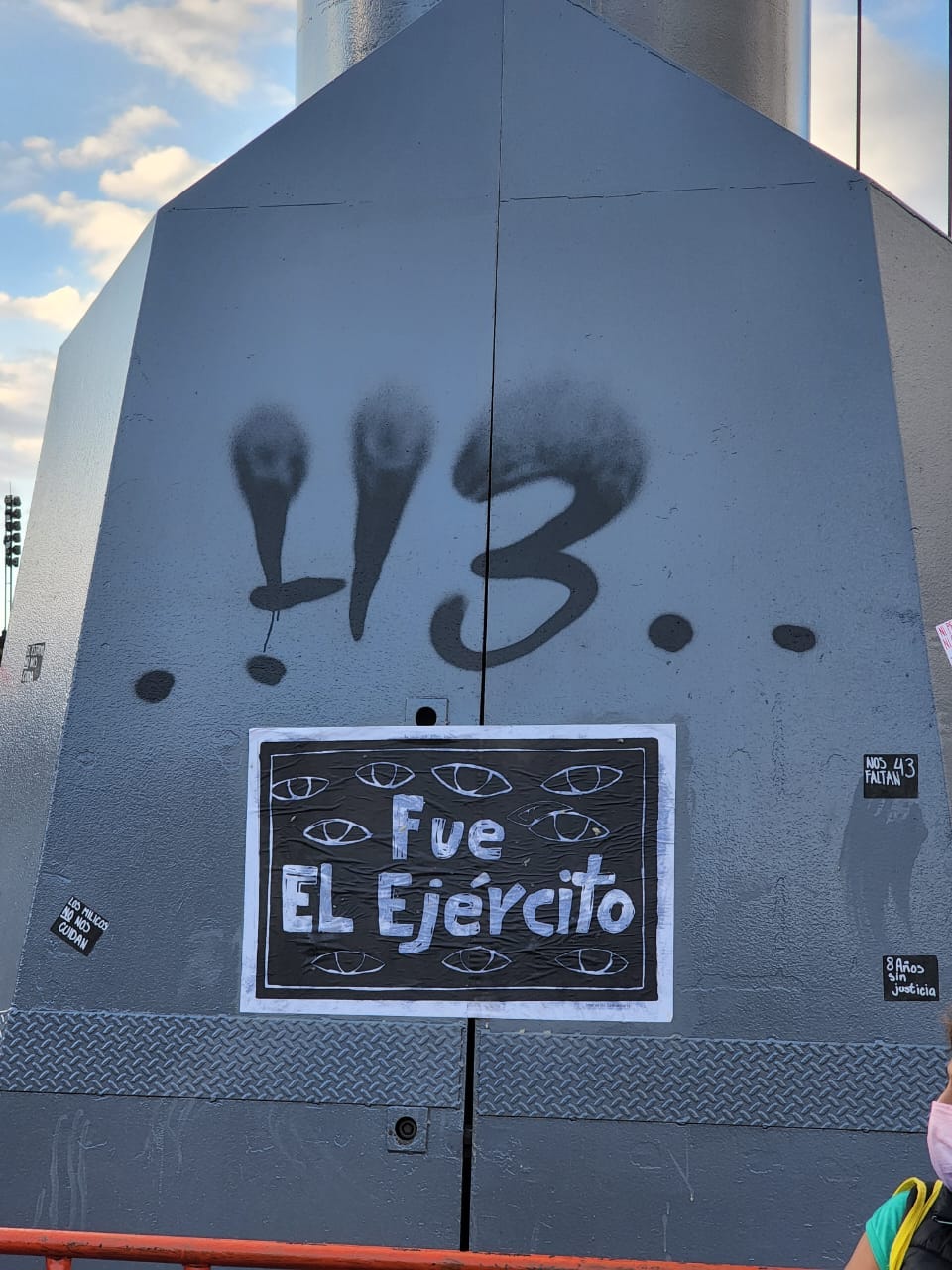

Under Peña Nieto, officials were told to stop talking about cartels and to speak about economic reform and investment; a tactic described in his circles as “changing the narrative.” The soldiers stayed on the streets and still took down kingpins. But Peña Nieto didn’t employ martial language and capos weren’t made to confess on TV. Murders first went down somewhat but then shot up to new highs and tragedies such as the disappearance of the Ayotzinapa students forced the violence onto the front page.

AMLO finally seized the drug war issue in the 2018 election, amid a rising criticism of massacres carried out by both gangsters and the security forces. Speaking in Mazatlán on the trail, he promised, “There will be no more massacres. They are even killing the injured. No more. This is inhumane. You can’t abandon the youth and then when they take the wrong path massacre them.”

This notion that too many youths pick up Kalashnikovs and join cartels because of poverty is of course right. The idea of abrazos, explains political scientist Lorenzo Meyer, is about society reaching out to the poor to heal these wounds.

“For centuries, Mexican society has been the subject of the extraction of wealth by the elite,” Meyer tells me. “The idea of hugs not bullets is to create incentives so young people will not be recruited by organized crime…These are the hugs. It is the upper part of society hugging those at the bottom.”

AMLO won the 2018 election with more than twice the ballots of the next candidate, perhaps the best ever result in a Mexican vote that wasn’t rigged.

The Reality of Power

The problem was that when AMLO took office, he struggled to find concrete policies for this notion of restoring peace. He didn’t assemble a great team. His public security secretary Alfonso Durazo had little security experience and has since left to become a governor. His interior secretary Olga Sánchez Cordero had no governing experience and has left to become a senator.

At the get-go, Sánchez Cordero led efforts for an “amnesty for the millions who had been recruited by organized crime” – which could demobilize cartel gunmen. But amid anger that it would put murderers and kidnappers on the street, it whittled down to a law that has given reduced sentences to about 2,000 people, who are largely nothing to do with cartels.

AMLO is conservative on legalization and did not embrace drug policy reform that could take away the cartel financing. While Mexico’s supreme court ruled it is unconstitutional to prohibit cannabis, the Senate has stalled on passing a law on how this would work.

On the other hand, AMLO has put money into social programs for the poor, one of his flagship policies. But most resources are in general schemes rather than focused crime prevention that can have an immediate impact in barrios where cartels recruit. AMLO was also hit by the Covid recession that threw millions into poverty.

One real difference in AMLO’s security policy is a shift away from the “kingpin strategy,” of taking down top narcos. There have still been a few bosses arrested such as the infamous Rafael Caro Quintero, who the DEA wanted for his role in the murder of its agent Enrique Camarena. But he was likely a minor player by the end. This contrasts with the days of Calderón and Peña Nieto, when forces took down heads of all the major cartels.

The kingpin strategy is highly problematic because it increases violence; when the big capos fall their bloodthirsty lieutenants fight over their empires. But AMLO showed that the alternative is not good either, allowing murderous gangsters to go free. This was illustrated by the release of Chapo’s son Ovidio Guzmán in 2019.

In the infamous episode known as the Culiacanazo, soldiers arrested Ovidio on a U.S. warrant but after hundreds of cartel gunmen hit the streets, Durazo ordered the troops to let him go. Some Culiacán residents argue it was a good move as the gunmen could have massacred civilians. But it was also fiercely criticized for being like a green light for gangsters to act with impunity. Many also see a wanted criminal walking as a sign of Mexico’s good old narco corruption.

This corruption is perhaps the biggest obstacle to making any headway in fighting organized crime. And it goes back as long as people have been smuggling drugs from Mexico to the United States (a 1916 investigation found the Baja California governor worked with opium peddlers). Corruption has plagued all the recent administrations, with the very secretary of public security under Calderón now in prison in the United States on trafficking charges. This feeds the argument that the entire drug war is a farce.

AMLO made the fight against corruption a cornerstone of his campaign, saying he would start with top officials, or “sweep the stairs from the top down.” But there are still plenty of accusations of narco links to members of his Morena party, including in Sinaloa, Michoacan and Tamaulipas. The old mafia of power could have been replaced by a new one.

Without significant advances in crime prevention, fighting corruption, or drug policy reform, murders have continued at the sky-high level of well over 30,000 a year. Critics point out that the the first three years of AMLO’s administration has been the bloodiest in recent decades. In his defense, AMLO retorts that he inherited a huge homicide count and it is finally going down somewhat. But even if you concede this point, he is still governing over unacceptable levels of bloodshed.

Amid this challenge, AMLO has turned increasingly to the army.

The Army-Industrial Complex

All four Mexican presidents this century have tried to improve law enforcement by shuffling around agencies and creating new forces. The direction has gone clearly from the states to the federal. Vicente Fox created the Federal Investigation Agency, which was billed as the Mexican FBI; Calderón boosted the federal police to a force of 37,000; Peña Nieto created a national “gendarmerie” (or at least pretended to); AMLO has launched the National Guard.

One factor is that cartel gunmen are heavily armed with AK’s, 50 cals and grenades and often outgun local police. State governors can also wash their hands of the narco problem and say it falls on the federal government. A third factor is that federal forces are hungry for the budget.

There have been periodic attempts to fix state and city police, “purging” forces of narcos and giving officers psychometric tests. And various corps of state police have themselves become militarized. But overall, local forces remain weak, corrupt and massively ineffective in solving crimes. Across Mexico, there is impunity in about 90 percent of murders, so if you kill someone you have a nine in ten chance of getting away with it.

It’s easy and justifiable to cry that Mexico’s priority should be to reduce impunity. But it is a Herculean task when police departments have a backlog of a quarter of a million unsolved murders from the last decade. Meanwhile, AMLO likes to deliver concrete projects that people can physically see, such as building airports and trains. Creating the National Guard, a new force in a new uniform, fits with his vision of what he calls Mexico’s “Fourth Transformation.”

The problem arose when the Guardia struggled to recruit. It is still unclear whether people were scared of the risks or whether army officers resisted the newbies who would dilute their forces. AMLO had angered army officers when he criticized them under Peña Nieto and ordered them to stand down in the Culiacanazo.

AMLO’s relationship with the army improved with the affair of Salvador Cienfuegos, the former defense secretary. Cienfuegos infamously flew to Los Angeles in 2020 and was arrested on a drug trafficking indictment. AMLO initially responded that this showed the corruption of previous administrations. But he quickly changed his tune, reportedly after a sit down with top military officers. Instead, he worked with the Trump White House (and maybe with Trump himself) to get Cienfuegos sent to Mexico where he was duly released without charges. AMLO gained massive points with the militia

As AMLO’s relationship with the generals strengthened, he gave them more responsibilities, and in turn more budget. Soldiers not only built AMLO’s pet new airport in Mexico State and run land customs, but they get to build more airports and run his Train Maya project. The army is becoming one of the biggest enterprises in the country.

AMLO also decreed that the regular army will stay on the streets until the end of his administration, despite pledges that he would send soldiers back to the barracks. A problem is that when heavy violence flares up, such as in Michoacán or in Tamaulipas, Mexican officials often see no other short-term option than sending in troops. Another issue is that despite criticism by civil society groups, the army remains broadly popular. A survey published in El Universal found 80 percent in favor of the army being in the fight against organized crime.

The Guardia goes on joint operations with regular soldiers and became effectively controlled by the army. When I requested a ride along with the Guardia as part of a documentary, they sent me to the army for permission. The law to officially shift the command to the generals moved rapidly through Mexico’s Congress in August, before the opposition could organize against it, and it was published on September 10.

Part of the idea of the Guardia is to act as a deterrent, putting boots on the ground to stop armed groups operating openly. Sometimes this works, but sometimes the cartel gunmen move around and have shootouts despite them. In several states run by AMLO’s Morena, generals have also been put in charge of the state police and they go on more aggressive operations with the guards and regular army. This could well be the shape of things to come. It remains to see how effective it will be.

So how will this all play out in in the hands of AMLO’s successors? The analyst Hope thinks there is little chance of an actual coup but a big chance of the army exerting too much influence.

“The creation of a military industrial complex has been probably the most appalling part of the AMLO legacy,” he said. “The military and its companies could become addicted to public subsidies. Once they have an airport why not an airline? Why not hotel chains?...This is aiming at something like Pakistan. Something like Egypt.”

Some authoritarian countries, such as Cuba or China, at least have a low crime rate. But others, such as Venezuela, suffer an authoritarian government alongside runaway crime. It would be tragic if a militarized Mexico were headed to this worst of both worlds.

All photos by Ioan Grillo except top photo by Erik Camargo and meme

Copyright Ioan Grillo and CrashOut Media 2022

Great article! Cheers.

Been a fan of Ioan's books for a few years now and just discovered and subscribed to this Substack. I had high expectations and still came out impressed.

This is hands-down the best article I've read about amlo's security policy. Comprehensive, nonpartisan, thorough, direct.

It's been fascinating to me seeing the shift in amlo's doctrine, it seems like what started as "Abrazos, no balazos" turned into "abrazos, a veces balazos" and is now in the "abrazos, también balazos" phase.

I think any serious attempt at combating the narco problem must be two-pronged: the abrazos side must ensure our youth has real chances at quality education and dignified work ie. livable wages and work/life balance. The bitter balazos aspect should be a strong military deterrence policy aimed at keeping the population safe from extortion, human trafficking, and collateral damage from cartel in-fighting.

While our military is far from perfect and certainly not immune to corruption, I believe it is our most solid gov't institution and currently the best tool for the job (im talking about both SEDENA and SEMAR). In online circles, this is a controversial opinion, but as the article says, most people are in favor of military prescence in our streets.

Cheers and good day, everybody.