When "Los Palillos" Dissolved Bodies in California

The Tijuana Cartel breakaway used a honey trap to seduce victims for their gruesome U.S. murder trail

Para leer en español click aquí.

The cartel war is not only south of the Rio Grande. This is part of a series on cartel operations inside the United States. I also have stories on the “Chicago Cocaine Twins,” the Mano Negra of Central California, the Goshen massacre, and infiltration in the Border Patrol.

After strangling the two victims, the gangsters threw their bodies head-first into barrels of acid, using the techniques of an infamous Tijuana killer known as “El Pozolero” or “The Stewmaker.” They buried the remaining bones and flesh in arid ground under a horse ranch. The macabre burial site was not in Mexico however but north of the border in San Ysidro on the outskirts of San Diego.

The 2007 murder was the work of a gang called “Los Palillos,” a breakaway from the Tijuana Cartel that went on a kidnap and murder spree that took the lives of at least fourteen victims in the United States, both in California and as far away as Kansas City, Missouri. They also dressed up as U.S. cops, shot at a real Chula Vista officer, and held hostages (mostly other cartel affiliates) for ransom in suburban San Diego homes.

Cartel sicarios slay the vast majority of their victims in Mexico, which has suffered more than 400,000 murders since 2006. The traffickers prefer to keep things quiet in the United States where they are making billions of dollars selling drugs. However, there have been a few notable sprees of cartel violence on U.S. soil. The Zetas unleashed a string of homicides in southeast Texas and “El Mano Negra” quietly did hits for decades. But perhaps the worst cartel spillover was the Palillos murder trail in Southern California the 2000s.

While media did cover the Palillos case, most Americans haven’t heard of it. Local police initially struggled to connect dots on the various bodies, especially in different states. Evidence came out gradually and it took two years after the acidified corpses were buried before agents discovered them. Courts convicted most Palillos members in trials in the 2010s, but some gang members are still at large.

Agents who cracked the case have now retired and are able to speak more freely about it. Among them is Steve Duncan, a hardened agent who knows as much as anyone in U.S. law enforcement about cartels: he worked for the California Department of Justice and was in a task force that brought down the Tijuana Cartel. While most of the Palillos’ victims were themselves linked to traffickers, Duncan says it was crucial to stop them murdering on U.S. soil.

“They are doing it on our territory and they are getting away with it. And eventually someone innocent is going to get hurt,” Duncan says. “Because a Chula Vista police officer got shot at, it really motivated us to get going…That was a huge deal. We were pissed.”

While tragic and brutal, the Palillos story plays out like an action movie. It involves betrayal and disrespect, luring victims with honey traps, and shoot-outs on California streets. And it ends with a spectacular take down and most of the culprits going to jail.

In this case, U.S. law enforcement finally stopped the cartel getting away with murder north of the border. But they might not hold that line for ever.

“It’s important that people know that this can happen,” Duncan says.

“Called To The Carpet”

Like many cartel capers, the Palillos case begins in a night club. The way it played out illustrates how Mexican organized crime really functions on the street level.

In 2002, according to the investigation, two crews that both worked for the Tijuana Cartel were out partying in one of the Mexican border city’s lively spots when they got into an argument. The dispute, which was supposedly over a girl, was between a gangster known as El Cholo and another known as Monkey, who pulled out a gun.

Cholo held a higher rank as a lieutenant and what’s more was married into the Arellano Félix family, which had run Tijuana as a personal fiefdom since the 1980s. So Cholo went to the cartel boss Francisco Javier Arellano Félix, “El Tigrillo,” and demanded Monkey be punished.

Monkey worked for a trafficker called Victor Rojas López, known as “El Palillo,” or “Tooth Pick,” for his skinny build. Tigrillo got hold of Palillo and “called him to the carpet” (called him to give account) and said he had to execute his own gunman Monkey for the act of disrespect.

“They tell Palillo, ‘You need to take care of your own guy. You need to take care of the problem,’ ” Duncan says. “But Victor [Palillo] didn’t take care of his guy so they take care of Victor. Then they put out a green light on the whole crew.”

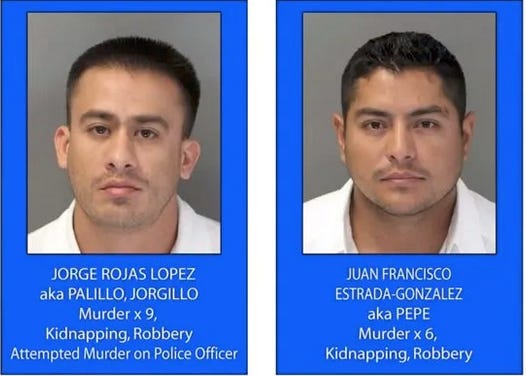

Sicarios shot dead Victor in his BMW 7 Series. (They were also resentful about him for being flash, a confidential source told agents). His brother Jorge Rojas López became head of the crew, took over the old nickname “Palillo” and swore revenge. But as they were less than twenty against hundreds of cartel gunmen, the “Palillos” had to run from Tijuana.

“They flee to the United States and they are living in south San Diego by the border. And they are pissed,” Duncan says. “You had a group that was banished from Tijuana.”

It’s notable that the Palillos had split from the main cartel and were a desperate band of renegades. So they broke the rules and brought the violence into the United States. This follows a pattern with cartel bloodshed north of the border, which is often carried out by upstart groups. The Zetas were a new faction fighting older cartel bosses when they carried out their killing spree in Texas.

The Palillos didn’t have the network to move big quantities of drugs and couldn’t go into Tijuana without being hit. So they turned to the savage crime of kidnapping for ransom. Their targets were the businessman associates of the Arellano Félix in San Diego.

Hook Up At The Gym

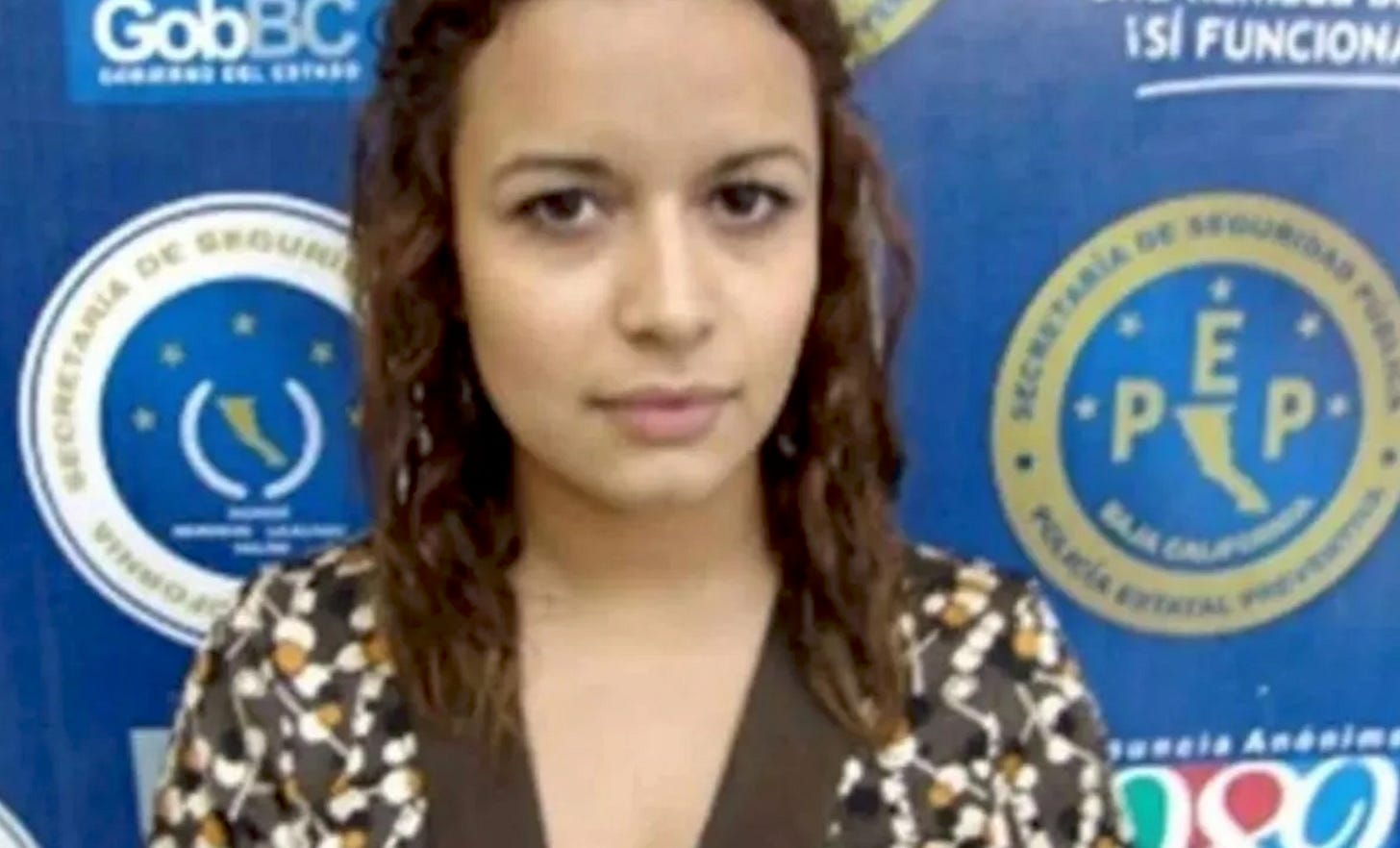

The modus operandi of the Palillos was to profile a target and set them up for a kidnapping. Sometimes they lured them into a house to be abducted by pretending to buy drugs or do other business. But they also used honey traps, especially utilizing Nancy Mendoza, a teenager from Tijuana who dreamed of being a lawyer but became the girlfriend of the Palillos leader.

She zeroed in on some targets in an L.A. Fitness gym in Chula Vista, a city near the border. “She would befriend them first, ask for help at the gym, ‘Can you help me with this exercise’ ,” Duncan says. When she finally lured them into her supposed home, they would be tasered and tied up.

The Palillos kept victims in houses in quiet suburbs around San Diego while they demanded ransoms, sometimes in the millions of dollars. The families would rustle up what they could, normally a few hundred thousand in backpacks of cash along with jewelry and Rolex watches.

In a few cases, the Palillos released the hostages after payment. But in most, they simply killed them once they had the money. They even rubbed it in by dumping the bodies publicly, sometimes throwing toothpicks over them. Maybe, they were so pissed they didn’t care. Or perhaps they deliberately wanted to bring heat on the Arellano Félix cartel, or “calentar la plaza.”

Despite the blatant violence, police were slow to figure out they were looking at a single organized crime case. “Nobody was responding to it, or pulling their resources or sharing their information,” Duncan says. “It was obvious that they were cartel related but the initial detective on the case wasn’t sharing his information with people he should have.”

To complicate it further, the Palillos had set up operations over in Kansas City and Miami, making it harder to track them. They left two bodies in the farming town of Jameson near Kansas City. They grew from the original band who fled Tijuana by recruiting new members including Cubans.

Perhaps they could have got away with it for much longer. But then the Palillos overplayed their hand by trying to kill a Chula Vista cop.

Agent Steve Duncan

Take Down

The Palillos took it up a level in September 2005 when a group including Monkey dressed up as police officers using kits and badges they had purchased at a San Diego uniform store. In their cop disguises, they tried to raid a cartel dope house in Chula Vista.

But their robbery went belly up. The cartel operative barricaded himself in and when the Palillos shot the door up, a neighbor called the cops and they got chased by a real Chula Vista policeman. The Palillos didn’t stop there but led the officer into an ambush, firing into his car. The officer jumped out the vehicle and was lucky to survive. He managed to call back-up who arrested Monkey and a cohort.

The attack was a wake-up call about violence spilling over from Mexico. Agents then got info from an intercepted call about Monkey’s involvement in another murder of an Arellano Félix marijuana seller in Chula Vista. “It was at this point that we knew we had renegades in San Diego hunting associates of the AFO [Arellano Felix Organization],” Duncan says.

Still it would take another two years and more kidnappings and murders before officers took down the Palillos. A big issue was that families of victims wouldn’t go to the cops both because of their involvement in trafficking and because they were terrified of the kidnappers. Duncan and other agents were also busy in an intense operation against the main cartel leadership in Tijuana. They set up a long elaborate sting that led to the U.S. Coast Guard nabbing the Arellano Félix boss “El Tigrillo” while he was partying on a yacht in international waters in 2006.

This arrest inadvertently helped get info on the Palillos. One of the men nabbed for shooting at the cop reached out to agents to cooperate against El Tigrillo. By doing so, he gave the game away about the renegades in San Diego.

“He put a lot of the pieces together and it told me where to look,” Duncan says. “And it told me that I need to put a bulletin out to law enforcement ASAP.”

Officers came back with the reports of scattered abductions and murders and they created a kidnapping working group of DEA, FBI, California Justice Department, San Diego District Attorney’s Office, and San Diego Police and Sheriff’s Department.

“We look back at the cases and see they are related,” Duncan says. The cops were even able to find that almost all of the victims were tased by the same gun (tasers leave unique tracing).

The anti-kidnapping squad finally managed to get the wife of one of the victims to work with them. In June 2007, the honey trap Nancy Mendoza lured wealthy businessman Eduardo Gonzalez-Tostado (again linked to the Arellano Félix) to be abducted. Tostado had been scared that he could be a target and had given the FBI number to his wife who phoned it in.

The agents set up a controlled ransom payment of $193,000 in marked bills tracked by surveillance and phone taps. This led a SWAT team to raid a house in Chula Vista, rescuing Tostado and getting six of the Palillos, including Jorge Rojas López himself.

The reign of the Palillos was over. But the case dragged on for years. More Palillos members were indicted (making a total of 18) and further arrests made. In 2009, agents found the dissolved bodies on the horse ranch.

Federal prosecutors had issues with the case so agents “took it across the street” and California prosecutors nailed it. They almost succeeded in getting a death penalty for leader Rojas López but after a deadlocked jury he was given multiple life sentences. Nancy Mendoza was arrested in Tijuana and extradited and also got life.

I ask Duncan whether such cartel murder sprees could be happening now, whether U.S. cops will continue to hold the line.

“It does happen and it’s going to continue to happen but it’s contingent on law enforcement to hold them accountable,” Duncan replies. “If they see the opportunity to get away with it they are going to do it.”

Copyright Ioan Grillo and CrashOutMedia 2024

When Are we gonna be able to get a Scarface remake using Mexicans?

Your last question to Duncan provided the most revealing answer. It is not contingent on law enforcement to hold them accountable because law enforcement does not control it's budget and they under the control and management by politicians and the police chiefs that are appointed by the politicians. The rank and file of law enforcement is crushed by the duplicitous objectives governing the political classes running American cities, political classes that are mired in corruption and criminal activity that no one dares to imagine or say out loud. The whole defund the police movement is a smoke screen to coverup layers of crime and corruption to the point many of our cities and towns are unlivable. On You Tube you will see video tours of the complete collapse of the belly of America.

It is only natural that law enforcement continues to think they can make a difference. But that ability was destroyed a long time ago especially when you look at our so-called models of Federal Law Enforcement which defy the suggestion that they are involved in law enforcement.