Interview With The Chicago Cocaine Twin

Margarito Flores, who flipped on El Chapo, looks for redemption

Para leer en español click aquí.

El Chapo was the hardest drug lord to deal with when you were buying tons of cocaine, Margarito Flores tells me. “Our first dealings with him, his organization kidnapped my brother,” he says. El Mayo, in contrast, treated him like a son. “He was a fierce man but he was also one of the fairest.” Arturo Beltrán Leyva, despite being less famous, moved more weight than either Chapo or Mayo. “On the business side, I think he’s unmatched.” El Mencho, however, was always trying to prove himself with violence. “He had that chip on his shoulder, a violent man from the beginning.”

Margarito is talking to me on a video call about his years working with his twin brother Pedro as the top distributors for the Sinaloa Cartel in the United States. They confessed to shifting over 60 tons of cocaine as well as heroin and crystal meth, enough for sixty million baggies of powder worth billions of dollars on American streets. The twins used their hometown of Chicago as a hub but moved the dope to a dozen cities including New York and up to Canada.

In 2008, however, the twins “flipped,” as DEA agents say, and became cooperators. For nine months, they continued to work in Mexico while recording narcos, including a phone conversation about a heroin deal with El Chapo that would be played in his 2018 trial. After they finally handed themselves in, their evidence was used in the indictments of over 50 traffickers and instead of a life sentence they served 12 years behind bars, many of those segregated for their safety.

Since his release, Margarito is still watching his back but he’s been trying to turn his life around and rehabilitate himself. He’s giving classes to law enforcement about the inner workings of cartels with a group called Dynamic Police Training and testified before the Congressional “Task Force to Combat Mexican Drug Cartels,” headed by Rep. Dan Crenshaw.

“I have a feeling, or this need, to do something with all my knowledge,” he says. “I want to make sure that by the time I leave here my legacy is something positive.”

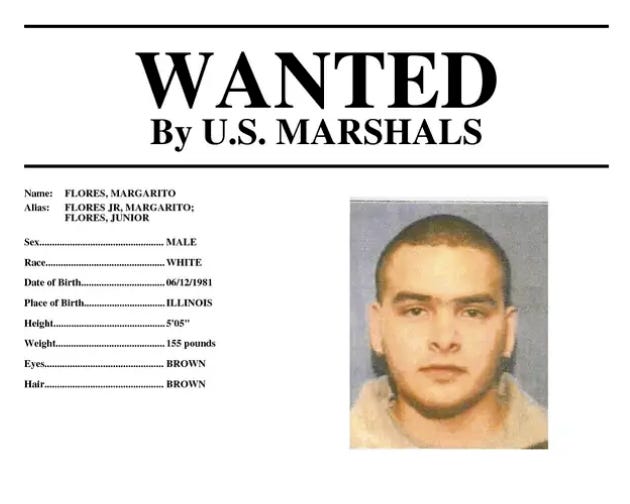

Known as J, short for Junior, Margarito is 42, but looks younger, with thick cropped hair and wide alert eyes. He’s driven and talkative, disarming with his an easy manner, a lively mind jumping from details of his trafficking logistics to books he read in prison. He knows both the world of Chicago’s Little Village where he was born, and small-town Zacatecas, Mexico, where his father hails from and he considers his second home. He speaks with a Chicago Latino accent as you can hear below.

While Margarito ran with bloodthirsty men, he doesn’t have an aggressive demeanor and wasn’t convicted of violence. Yet he was key to networks that have pumped narcotics into America and drowned Mexico in blood. Mexican drug traffickers would make nothing without U.S. associates to move their product north of the river. “Chapo or Mayo or Arturo couldn’t do what we did in the United States,” he says.

The twins made more bank than many of the infamous drug lords south of the border. Mexican journalists complain the U.S. side of the trafficking equation is poorly documented; Margarito sheds needed light on it.

As he says in the clip above, he was literally born into the life. When his mother was pregnant with the twins, their father was incarcerated for 11 kilos of black tar heroin. The twins grew up with an older brother who became a shot caller for the Latin Kings, a fearsome street gang, as well as a major drug dealer. His father came out of prison and kicked his gang-banger brothers out the house, but then took the twins down to Mexico for their first drug run. They were seven years old.

By 17, the twins made the first deal that they owned - of 30 kilos of cocaine - and by 20, they were shifting over a ton a month and making millions. But their ascent took them to the warlords at the very top of the Sinaloan mob as they erupted into a brutal battle that would tear Mexico apart. “We were threatened by the two most powerful, most violent, drug cartels I would say in the world at that time.”

Chicago Street Life

Born in 1981, Margarito grew up in the crack era and some bloody years in Chicago. With his dad locked up, his home would be a hangout for the neighborhood gang.

“I didn’t have your regular childhood,” he says. “My brothers were in the most violent, biggest organization which was the Latin Kings…I am basically being raised in that kind of culture.”

When his dad came out of prison, however, he was furious. Margarito Sr was an old-school narco from Zacatecas and forbade the twins from what he saw as the crude tattooed life of gang bangers. “He despised gang members, believe it or not. It’s this weird contradiction. Because he was in prison with them. He didn’t understand their reasoning.”

Their father’s idea of education, meanwhile, was taking the twins down to Mexico to buy marijuana and drive it back to Chicago. On their first trip at seven they thought it was a fun vacation as they helped stash weed in the gas tank. Over the following years, they learned how to find marijuana plantations in the mountains and negotiate with sellers. “My father made sure he introduced us to everyone, and made sure we treated everyone with respect.”

This unique background put the twins in a special place to link the drug lords in Mexico with gangs that sold drugs on U.S. streets. They knew both worlds but weren’t quite part of either. Instead they styled themselves as businessmen and had a higher level of education than most their counterparts. Even while they trafficked through their teenage years, Margarito got a high school diploma and Pedro did a couple of semesters of college.

When they were 12, their dad went on the run to Mexico and after a stint there the twins returned to Chicago to live with their Latin King brother - and help him deal drugs. After he too was sent to prison, they began making their own deals with Sinaloa Cartel intermediaries in Chicago. They rose quickly to be moving a ton a month by the time they were 20.

I ask Margarito if they got so big so fast because they were in the right place at the right time. He shakes his head. “Drug trafficking is not easy. People fail at it every day,” he says. “Prisons are filled with failed drug traffickers. Cemeteries are filled with failed drug traffickers.”

Moving quantities of dope in America, he explains, is about running a smooth logistical operation. The cartel needs the drugs delivered fast and the payment back faster. Traffickers who are slow to move loads and mess up on paying are the ones who get killed. The twins were workaholics who took care of every detail as they built a network of transport, especially of independent truck drivers, discreet stash houses that operators went to for loads, and crucially, money-counting machines

The profit margins depend on how much you pay per kilo brick of cocaine and how much you sell it for. Traffickers keep an eye on the prices in different cities like brokers watch stocks. The sale prices are higher the further north you go so the twins made money by delivering to the northeast and into Canada. And the buying prices are lower the higher up the chain you get; so the twins cut out the middle men and built relationships directly with the heads of the Sinaloa Cartel.

Drug Lords

Gaining the trust of the top players was not easy. In early 2005, an associate of El Chapo kidnapped the twin Pedro and held him for over two weeks, almost starving him to death. Margarito went to the mountains and negotiated with Chapo for his release and ended up paying off a debt that had been caused by Chapo’s own man messing up.

“Of all the drug lords I actually had business relationships with, he was probably the most difficult one,” Margarito says.

However, they finally gained Chapo’s approval to buy cocaine directly from the inner circle of Sinaloa drug lords at a cheaper rate. This would boost their trafficking to over three tons a month and up to ten million dollars in profit.

El Mayo (or Ismael Zambada) was easier to work with, praising their ability to move so much powder, and joking how much they could have moved if they were triplets. Now 76 years old, Mayo is the most veteran surviving drug lord and boasts a legendary status of smoothing relations and paying off cops (he’s never been in a jail cell.)

“He reminded me a lot, even nicer probably, than my father,” Margarito says. “I feel like he had genuine love and respect for us…When it came to any type of business, he would be like, ‘Whatever you guys decide and you know what, here is an extra something for you guys.’ It doesn’t surprise me that he continues to be the head of the organization, the most successful one for sure.”

U.S. prosecutors made their case against Chapo by saying he was the supreme head of the Sinaloa Cartel. But Margarito’s account paints a picture of a federation with a cupola of bosses. Among these, Arturo Beltrán Leyva, a roughneck known as Barbas, or The Beard, was actually moving more cocaine, Margarito says.

“He brought in a shipment of 20, 25 tons of cocaine, and you had to make a reservation, and in Mexico you deal in cash,” Margarito says. “He was a calculator like, I would grab my phone to calculate and before I even pressed a number, he was already telling you what it was. Big numbers. Like he was one of the best businessmen I feel like there was in drug trafficking.”

However, Beltrán Leyva also had a reputation for murder and even cannibalism. Margarito says it bothered him that he wasn’t as famous as Chapo and Mayo and he used violence to put himself on the map.

“It’s always about legacy…To them, you are your name,” he says. “No limit when it came to violence. He would do things to put exclamation points on.”

Another gangster with a reputation for blood was El Mencho, or Nemesio Oseguera. When Mexican federal agents arrested the twins in Jalisco, Mencho led a squad of gunmen to force their release. He was a rising figure then in a local group affiliated with the Sinaloa mob, but Margarito says he was an aggressive hungry guy and he didn’t like to do business with him. Mencho would go onto create the Jalisco New Generation Cartel with its vast paramilitary forces that sowed mass graves.

In 2008, these Sinaloan bosses broke into a bloody civil war. The violence had various fronts but a central battle was between Beltrán Leyva and Chapo - The Beard versus Shorty. As these old childhood friends turned into bitter enemies, their gunmen painted the streets of Sinaloa with blood. In May, sicarios fired 500 bullets into a son of Chapo, Édgar, at a Culiacán shopping mall and residents lived with ensuing daily revenge hits.

Both Chapo and Beltrán Leyva told the twins they had to choose their side. But the twins tried to play them off against each other. They wanted to gather evidence on both. Because by this time, they were working with the DEA.

Redemption?

Margarito has a tear in his eye when he describes their decision to cooperate. He realized his path would only lead to death or the Super Max but flipping gave him a glimmer of hope. “I had a spiritual epiphany one day,” he says. “I felt like, I wanted to do something good for my family.”

I’m reminded of something he said earlier in the interview. He described watching the movie Scarface as a kid. “The movie Scarface was a great story but it never motivated us to die like him.”

The twins began talking with DEA agents stationed in Mexico and recording their dealings with traffickers. As they were double agents, the war broke out. Now they were risking their life for both working with the wrong gangsters and for snitching. They also had to keep up moving dope to not expose themselves, but they were setting up their loads to get busted.

They made good undercovers. They knew they needed strong material to negotiate and their sentencing memorandum has a list of 54 recorded conversations with narcos. Finally, they got El Chapo himself on the phone. To lure him in, Pedro renegotiated the price of a batch of heroin they had already received. “In the drug business you don’t do that,” Margarito says. “You don’t receive a shipment and then try and get a better price.”

On Nov. 30, 2008, they handed themselves into custody and went from living the life of millionaire narcos to witnesses in jail cells. Their cooperation led to indictments against everybody: Chapo, Mayo, Beltrán Leyva, their sons and brothers and lieutenants, and even to members of the twins’ own organization in Chicago. They spent years alone in all day lockdown. In 2018, Pedro took the stand and testified against Chapo in his showcase trial in Brooklyn.

The twins were snitches. But then again, there are dozens of cartel snitches in the United States, including the brother and son of Mayo, the lieutenant of Chapo, El Damaso and his son and many more. The same effect happened to the Colombians in the 1990s inspiring the book, “El Cartel de Los Sapos” or “The Snitch Cartel.”

At least, Margarito says, they are alive and able to be fathers and husbands. Out of prison, Margarito is trying to remold himself, teaching law enforcement and helping the United States create a better strategy against cartels. He says it’s a struggle to get people to accept him but it’s satisfying when they do.

“This a cautionary story, we are not trying to promote the life at all,” Margarito says. “My brother and I were always applauded for bad, so now it feels good to go to an event where I am teaching law enforcement. Where I get a hug or I get a handshake or a standing ovation. And they tell me ‘Thank you.’ ”

Copyright Ioan Grillo and CrashOutMedia 2024

Great Job Ioan! He is an amazing young man with a fascinating story and you were able to bring it out gracefully.

Nicely woven story. Parts in Mexico. And many parts in the United States without there would be no business whatsoever. And the most crucial part. Myself deeply enmeshed for over 55 years. The user/retail buyer. I know without the part I fulfill this would all be for naught and not a business. Wrestle with this aspect every single day. These products become personalized in 100's of millions of people, like myself, across the entire world. Just Say No is applicable as Peace on Earth. Not happening.