Applied Math Versus Cartels

A study in Science finds cartels are Mexico's fifth biggest employer. Can you stop the gangsters recruiting faster than recruits are murdered?

Para leer en español click aquí.

NOTE from Nov. 14, 2025: This is a story from 2023 but sadly is still very relevant today, especially with the use of a 17 year old sicario in the assassination of Mayor Carlos Manzo. The central estimate of the number of cartel employees is a very useful one to understand the problem or organized crime in Mexico.

The sicario or “hit man” known as Juanito Pistolas was said to be recruited at just thirteen years old in the bloody border city of Nuevo Laredo, across from Laredo, Texas. Joining a murder squad with the chilling name of “La Tropa Del Infierno” (The Squad From Hell), he was celebrated in local rap songs for his love of gun fights.

“Age doesn’t matter to pull the trigger,” an emcee chants in the slurred style of Tamaulipas narco rap. “I’m a kid, but I go to work. Juanito Pistolas that’s what I’ve been nicknamed.”

Details of Juanito’s life are murky but he appears to be Juan Francisco Díaz born in 2002. A report claims his parents were slain by the same cartel that would recruit him. His infamy was short lived, however. In 2019, soldiers “eliminated” him in a fire-fight in which his head was literally blown off his shoulders. He’d just turned seventeen.

Juanito’s brutal yet tragic tale illustrates two key features of Mexico’s “drug war.” One is how cartels are able to recruit so many youths into their ranks with the allure of infamy and money. In cases like Juanito’s, they can correctly be called child soldiers. A second is how these recruits are treated like cannon fodder and so many of them perish. The sheer size of the body count in Mexico is astounding. Since President Felipe Calderón launched a military crackdown on cartels in December 2006, there have been almost 400,000 homicides with perhaps two-thirds linked to the conflict.

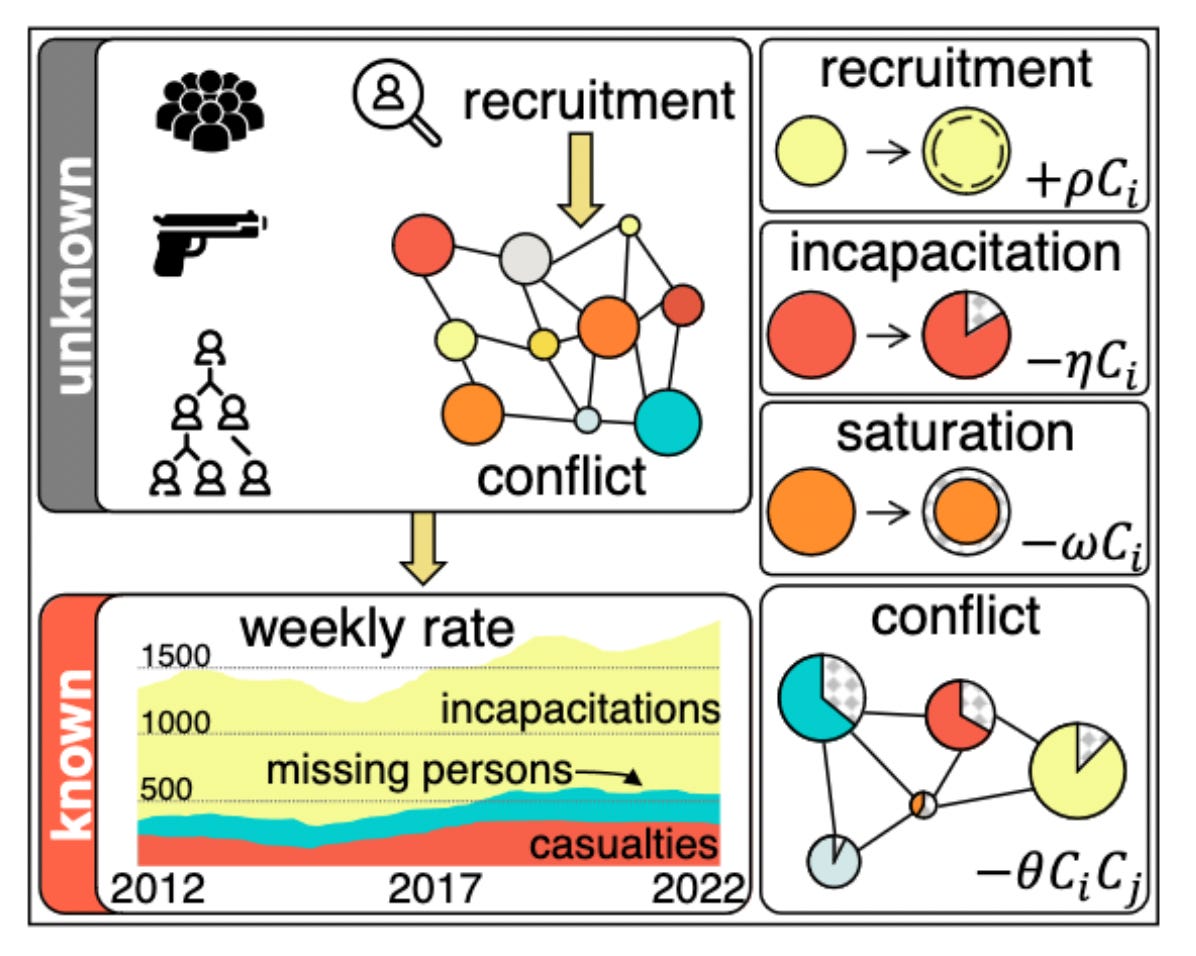

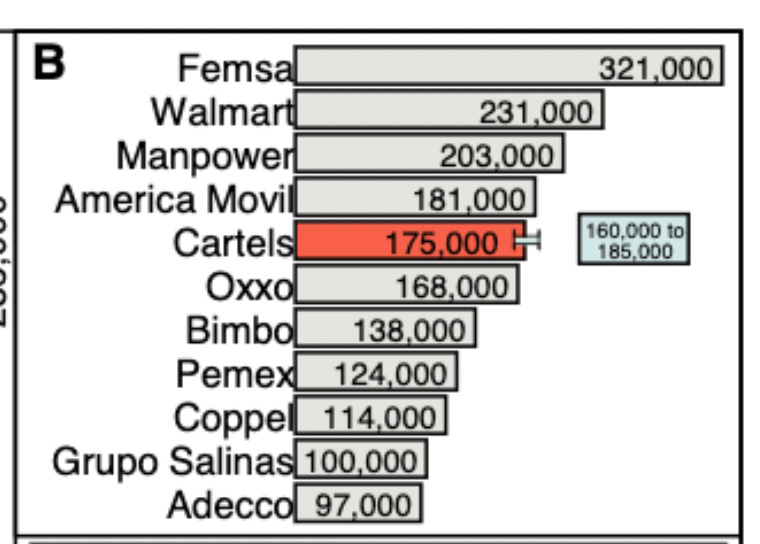

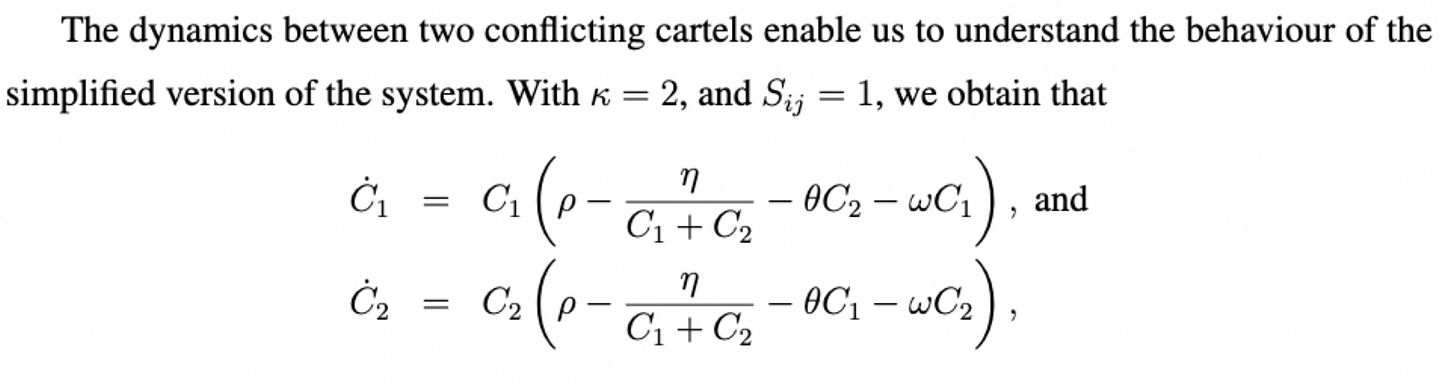

A new study published today in the journal Science by investigators Rafael Prieto-Curiel, Gian Maria Campedelli and the late Alejandro Hope, uses mathematics and data to try to put solid numbers on these problems and seek a solution. They create a model that finds cartels are one of the top employers in Mexico, with 160,000 to 185,000 members, and that they need to recruit at least 350 people per week to make up for those killed or imprisoned.

Even more worryingly, cartels have only been getting bigger over the last decade and the murder numbers have an overall tendency to keep increasing. The study’s conclusion is in its title: “Reducing cartel recruitment is the only way to lower violence in Mexico.”

“What is going to happen in the next five years? If we go on with the same policies, we are going to have an increase of 25 percent in the homicides in the country,” Prieto-Curiel told me in a Zoom interview. “Even if we arrested double the number of people we are arresting today then in 2027 we would still have 8 percent more homicides. And imagine, double the number of arrests, of police, of judges. It’s not going to work…What’s going to work? Focusing on cartel recruitment.”

Applied Mathematics vs Sicarios

Reading the study gives me both hope and reservations. Mexico is a country of paradoxes; on one side, it has super-marginalized youths like Juanito Pistolas; on the other, it has a sprawling middle class with a quarter of young people going to university and a significant number with advanced degrees. The author Prieto-Curiel has a doctorate in applied mathematics from UCL and did further studies at Oxford before going to the Complexity Science Hub in Vienna. This growing group of graduates may be key to breaking the cycle of bloodshed. The study tries to to get to grips with Mexico’s violence as a mathematical problem and look for an actual answer.

Furthermore, the study involved Alejandro Hope, a veteran security analyst and brilliant mind (and a friend), who died in April of natural causes at 52. Prieto-Curiel says it’s partly a tribute to him. I also instinctively agree with its conclusions: cartels do employ a hell of a lot of people, perhaps even more than the study finds, and it’s important to point out this colossal problem. Preventing youths from joining them has to be key to finding a way out of this mess.

On the flip side, it’s a mammoth challenge to turn the complex human interactions of Mexican organized crime into mathematical equations and I am skeptical of seeing formulas and precise numbers on it. Cartels don’t publish tax records and pay rolls. The study indeed recognizes these limitations. “Our work relies on a mathematical approach and, as in any other work that relies on similar methods, it is based on assumptions that are often hard to verify or test.”

There’s also the tricky question of how many cartel recruits double as state employees, carrying a police badge. And there’s a debate on how to classify cartels and who is really a member, or whether we should even use the term (which I’ll get into in another essay). The study goes for a broad definition, saying “we operationally define cartels as those criminal organisations that were found to be active in Mexico…regardless of their size and type of activity.” This includes not only drug traffickers but thugs who steal oil and do shakedowns as well as those who are in all these rackets at the same time.

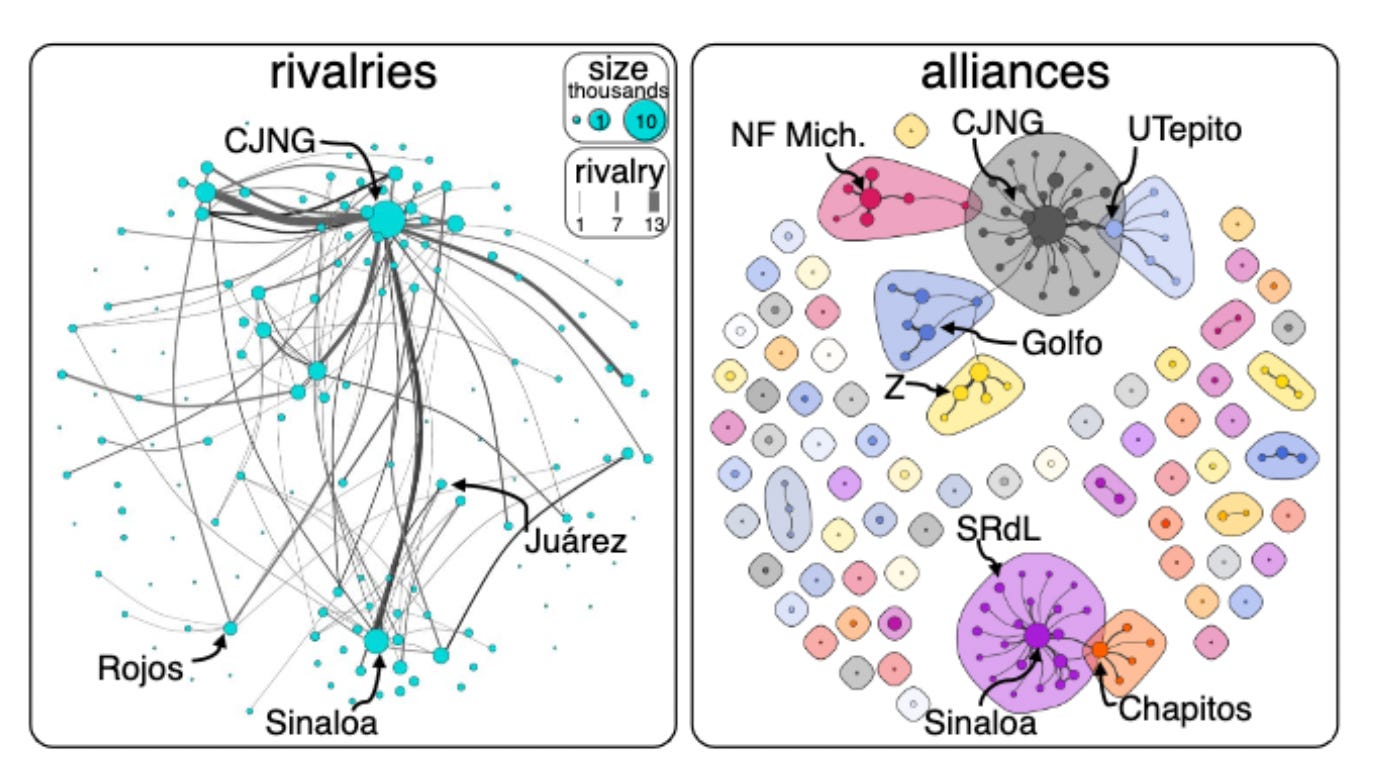

The study identifies 150 of these "cartels” from the major players to local gangs. However, the top 20 cartels have over two thirds of the recruits with the Jalisco New Generation Cartel at the peak, with an estimated 28,764 members (a very precise number!) followed by the Sinaloa Cartel with 17,825.

If the cartels were a single company, it observes, they would be the fifth largest private employer in Mexico between the grocery chain Oxxo and telecoms company América Móvil. While this is a bit comparing apples to oranges, it makes a solid point that organized crime is such a big part of the economy and of communities.

The study observes how different cartels have contrasting recruitment rates and looks at how this can affect the level of murders in different states. It’s certainly notable how varied the violence is across Mexico, and how it shifts from year to year, which has never been fully explained. It then takes into account how you can have one, two or multiple cartels in a territory and how the cartels can fight security forces but also disappear amid troop surges.

It uses this data to a form a series of equations like the above. It’s beyond my math to critique them and know how accurate they are. At best, they are useful estimates. Yet the same can be said of many studies on crime such as, “What Americans Spend on Illegal Drugs” developed by the Rand Corporation for the White House. And the answer to that question - about $150 billion a year - is very helpful to show the scale of the issue.

The most convincing and worrying thrust of the study is the prediction that the cartels continue to get bigger and the murder count could go higher still. In the thick of covering the violence, it can seem that it’s largely stable with just ups and downs from month to month. But taking a cold look at the numbers, the authors point out there is a clear a tendency upwards over the medium term. The worst could be still to come. Which is depressing and frightening.

Stopping The Child Soldiers

While Prieto-Curiel worked for a stint with Mexico City’s police department, he argues solidly for the prevention approach. This casts him apart from El Salvador’s president Nayib Bukele who has gone for an extreme carceral policy, locking up 1 percent of the population in an anti-gang crackdown.

“These criminals go with youths who are 11 to 15 years old, they offer them an income, or in some cases they have forced recruitment,” Prieto-Curiel tells me. “They make the cartel a desirable objective for the teenagers, with narco corridos, with parties…So at 14 years old they are at first look outs, and then a smuggler, then someone who collects money, and they start to get to a level in the cartel. They are recruited very young. But reducing the recruitment by cartels in the next five years, we will reduce the level of homicides.”

Prieto-Curiel is still cautious about the impact. If cartel recruitment halved, which would be tough, the homicides would go down by 30 percent, he predicts. This would still leave Mexico with a high murder rate, worse than a decade ago. “This is the saddest result I have come to in my scientific career,” he says. “They are going to go on killing. They have reasons to have conflict among themselves.”

Still, reducing the murders by 30 percent would be a massive achievement and would create an overall sensation of things getting better, and pave the way to achieving peace in the long term. But that is easier said than done. Both former president Enrique Peña Nieto and current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador have boasted about big prevention programs and neither have had an impact.

The failure, it seems to me, is in schemes that are too general rather than super focused to stop targeted youths falling into the hands of cartels. I have met great social workers on the ground from Monterrey to Ciudad Juárez who are effective at steering kids away from the mob, but the money often goes to political insiders close to the federal government.

Prieto-Curiel says that the key thing is for Mexican society to offer a better path than one that is so destructive. “Organized crime is offering Mexican youths one of the least beneficial careers that they can have, one of the most violent that exists in the world.” For the youths who are entering the cartels right know, his model predicts, 40 percent will be dead within a decade.

This mass culling of youngsters has been a startling feature of the bloodshed in Mexico. During the worst years of violence in Juárez, the mother of a gang member described how the boys in her neighborhood were being “wiped out like cockroaches.” In the Culiacán “narco graveyard” of Jardines del Humaya, there are so many young men buried, some with photos of themselves clutching guns or in fields of weed.

This imminent demise is embraced in elements of narco culture. As the rap about Juanito Pistolas goes on: “We are born to die. We’ll see each other in Hell.”

These youths need something better to live for than going down in a blaze of glory.

Photos released on social media by alleged cartel affiliates in 2015.

Copyright Ioan Grillo and CrashOut Media 2023

I believe a Christian revival among the youth of Mexico would dry up the cartel’s recruitment real quick. Only God can do that though. I’m going to begin to pray for it to happen.

Having been in Mexico to see family recently, it struck me that corruption has only gotten worse. I think that if the elite continues to let the rot undermine institutions, it is unlikely that drug war violence can be stopped. How can Mexicans generate employment on a mass scale when the system is so rigged, from schools to the highest levels of government? How can society provide a meaningful economic alternative to the glory of joining cartels?