Comic Relief in the Sinaloa War

Bobadilla finds gallows humor amid cartel violence

Para leer en español click aqui.

Residents of the Mexican city of Culiacán have been living through months of terror since a civil war broke out between the two main factions of the Sinaloa Cartel. Shoot-outs echo like fire crackers at a carnival. Gunmen abduct youths off the street. Soldiers backed by helicopter gunships sweep on safe houses. Mutilated-corpses stain dirt roads. Hundreds have died and disappeared.

It’s a tragedy to weep at. Yet some Sinaloans also manage to laugh at their hardship.

Culiacán native Ricardo Sánchez “Bobadilla” writes comic strips set in the bloodbath. Over the years, he has created various characters from the dark-side of Sinaloa including a pair of corrupt cops (“Los Cochipolicias”) but his most famous are a duo of sicarios, or hit men, called El Ñacas and El Tacuachi. The sicarios speak in thick Sinaloan slang and go about their bloody business of murder for money yet the cartoons also make cutting satirical commentary.

In this recent comic strip below for example, you see a man arriving in Culiacán amid the war.

“Excuse me. Where is the tourism office?” he asks.

“Why do you want to know?” the sicario replies.

“I want to make a complaint,” says the tourist. “I have been three days in the city and I haven’t seen a live shoot out.”

“Have patience,” the sicario says.

As a shoot-out erupts, the sicario kicks the tourist down. “On the floor, for fuck’s sake.”

After the fire-fight, the tourist returns home to his wife.

“I have brought a souvenir,” he says.

“What, a bust of Malverde [the narco saint]? Metal spikes to puncture tires?” his wife asks.

“One of the bullets that they took out of my spine,” he says and the frame shows the tourist in a wheelchair.

“Wow,” says his wife. “Thanks mi amor.”

As a reporter who goes to these hot spots, I find the joke hits painfully but it still gave me a belly laugh. I have known Bobadilla since I first went to Culiacán in 2008 and shared many a beer and menudo (cow-gut soup) with him on trips there. I caught up with him while running around crime scenes last month and interviewed him about drawing strips of gallows humor in the middle of a narco war-zone.

Bobadilla himself grew up in what was considered one of the most narco neighborhoods, Tierra Blanca, in the seventies and eighties. Buses would arrive from the drug-growing mountains of the “Golden Triangle” to his barrio with campesinos in sandals lugging sacks of opium gum. He would see guys on the streets that went onto become top bosses such as Guero Palma, El Azul and even El Chapo.

“My sister had a boyfriend who was friends with these people. Once they were in my house drinking in the garage. They got really drunk and started shooting in the air and they hit an electric transformer and the lights went out.”

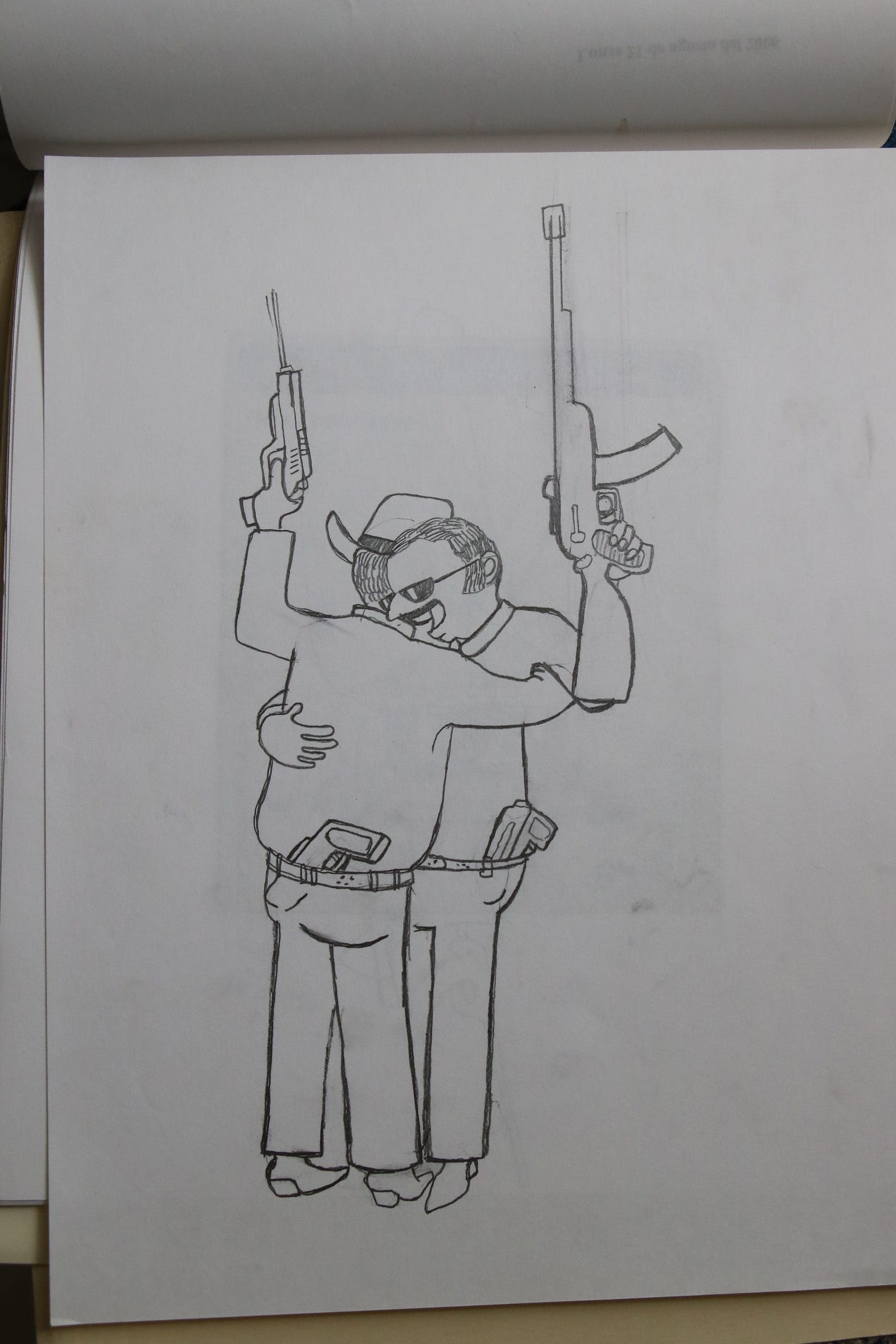

Ñacas and Tacuachi reflect the style of these old-school narcos that Bobadilla grew up around. They have sombreros and Ray-Ban sunglasses and shirts hanging out.

Bobadilla read American comic strips such as Peanuts and Archie. But he was particularly inspired by the Latin American satirical cartoonists. His favorite was the Argentine “El Negro” Fontanarrosa who drew a Dirty-Harry style mercenary, Boogie, that traveled round the globe starting trouble.

Bobadilla began doing more overtly political comic strips but he and some other Sinaloan cartoonists moved onto narco subjects because that is what they saw around them. The drug dealers, murders, corruption, were everywhere, there was no escape.

“When we started to speak about this it was to visualize it. Because that it was you see on the streets. And when you put it on paper or publish it, you are saying, ‘That is really going on.’ And you are leaving evidence.”

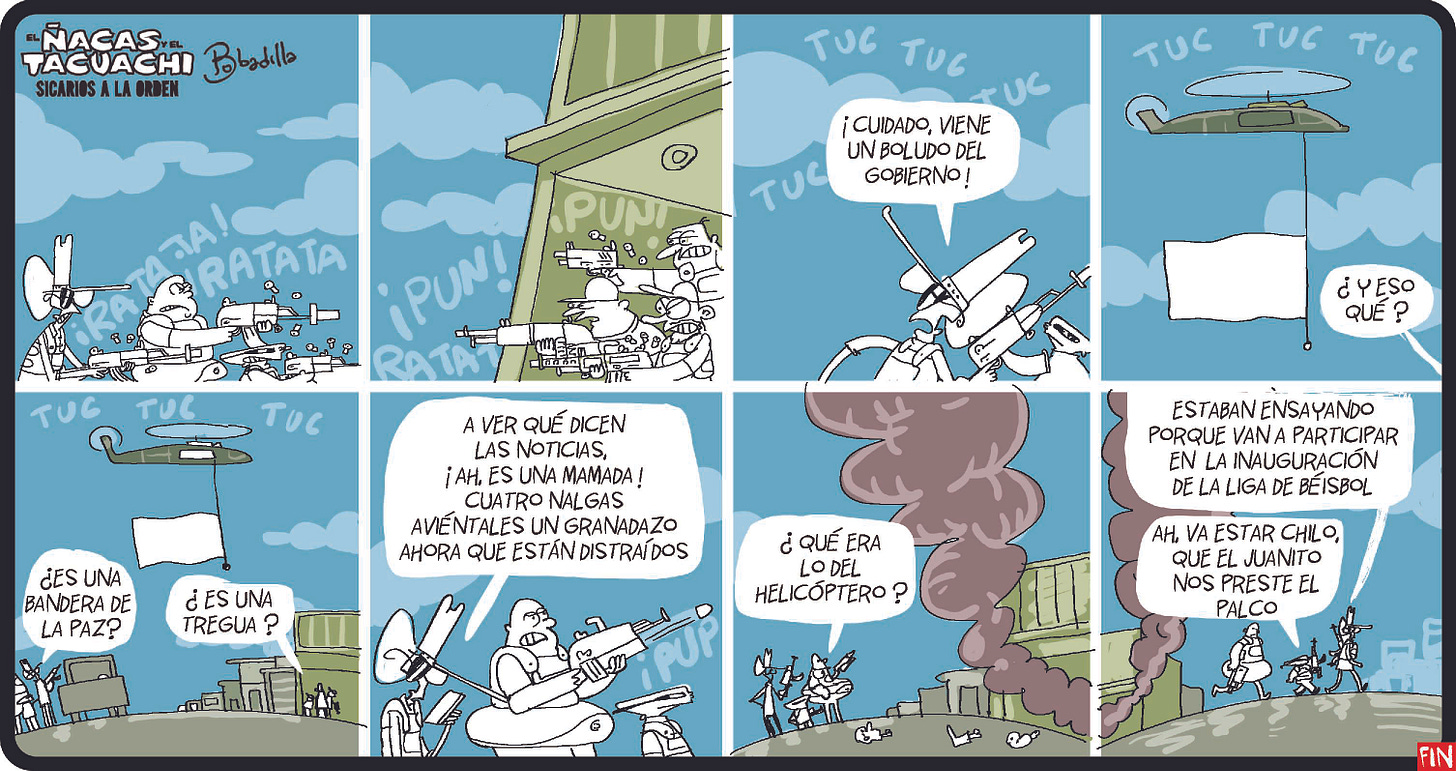

While being ultra-violent, Sinaloa can be simply surreal. The comic strip below shows a true event that happened recently. A helicopter flew with a white flag and residents thought a truce in the cartel war had been announced. But it was just a practice run to promote the start of the baseball season.

In the comic strip, as the white flag is flying, the sicario says, “Throw a grenade while they are distracted.” When they realize it’s for the baseball, his partner says, “Cool, Juanito can lend us his box.”

Ñacas and Tacuachi speak Sinaloan slang complete with curse words despite the fact Bobadilla publishes in regular newspapers including Rio Doce and El Debate. At first, editors were cautious about using dirty language as kids could read it. But Bobadilla said he had to write how they speak. However, he often writes the Sinaloan word “verga” meaning “prick” as just “erga,” like they say it on the street sometimes. It’s become a trademark and people will now recognize Bobadilla and shout, “Erga!”

For regular citizens in Culiacán, it’s a daily challenge not to get on the wrong side of narcos. “Although we are saying it with humor, if you stop before some guy and honk your horn, you could get killed,” Bobadilla says. “Or they shake you down. Or kidnap you.”

Bobadilla has personally suffered. In 2008, when a previous Sinaloa Cartel civil war erupted, his older brother Miguel was murdered. Miguel was buying ice pops with his wife when a guy pulled out a gun and shot him. Bobadilla believes it was simply a mistaken identity but the police, typically, never got to the bottom of the case.

“The detective received me and said, ‘Do you know how to use guns?’ No. “Do you have friends that are heavy or politicians?’ No. ‘So, don’t get involved.’ ”

Considering the pain his own family has suffered, I ask how he sees Ñacas and Tacuachi. Are they villains? Or heroes? Or anti-heroes?

“They are old school,” he replies. “Within the immorality of being a sicario, they have certain ethics, certain rules. They don’t kill children and women. They are generous. They can even be a bit gay. Or brutally tender. In real life, they are anti-heroes because that is how most people see them.”

Bobadilla recognizes there is a thin line between doing satire or criticism of narcos and glorifying them. However, the comics are not really part of what is understood as “narco culture,” which includes the drug ballads that traffickers personally finance to celebrate themselves. Yet, like so much in Sinaloa, the cartoons do reflect the drug world.

I ask Bobadilla if he thinks Ñacas and Tacuachi could retire some time when there is finally no more work for them. He laments the cartels are like a hydra and when you cut one head off then two grow back. But Ñacas and Tacuachi are shown in a comic strip with one worry: if the United States has a better health plan to get people out of drug addiction, they fret, it could affect their business.

Cartoons published with permission of Bobadilla

Photos by Fidel Durán

Text copyright Ioan Grillo and CrashOut Media 2024

I’m not going to lie, those strips were pretty funny.

Fascinating, as always.