America's Narco Snitch System

The U.S. government rampantly uses cartel cooperators; it raises serious questions

Para leer en español click aqui.

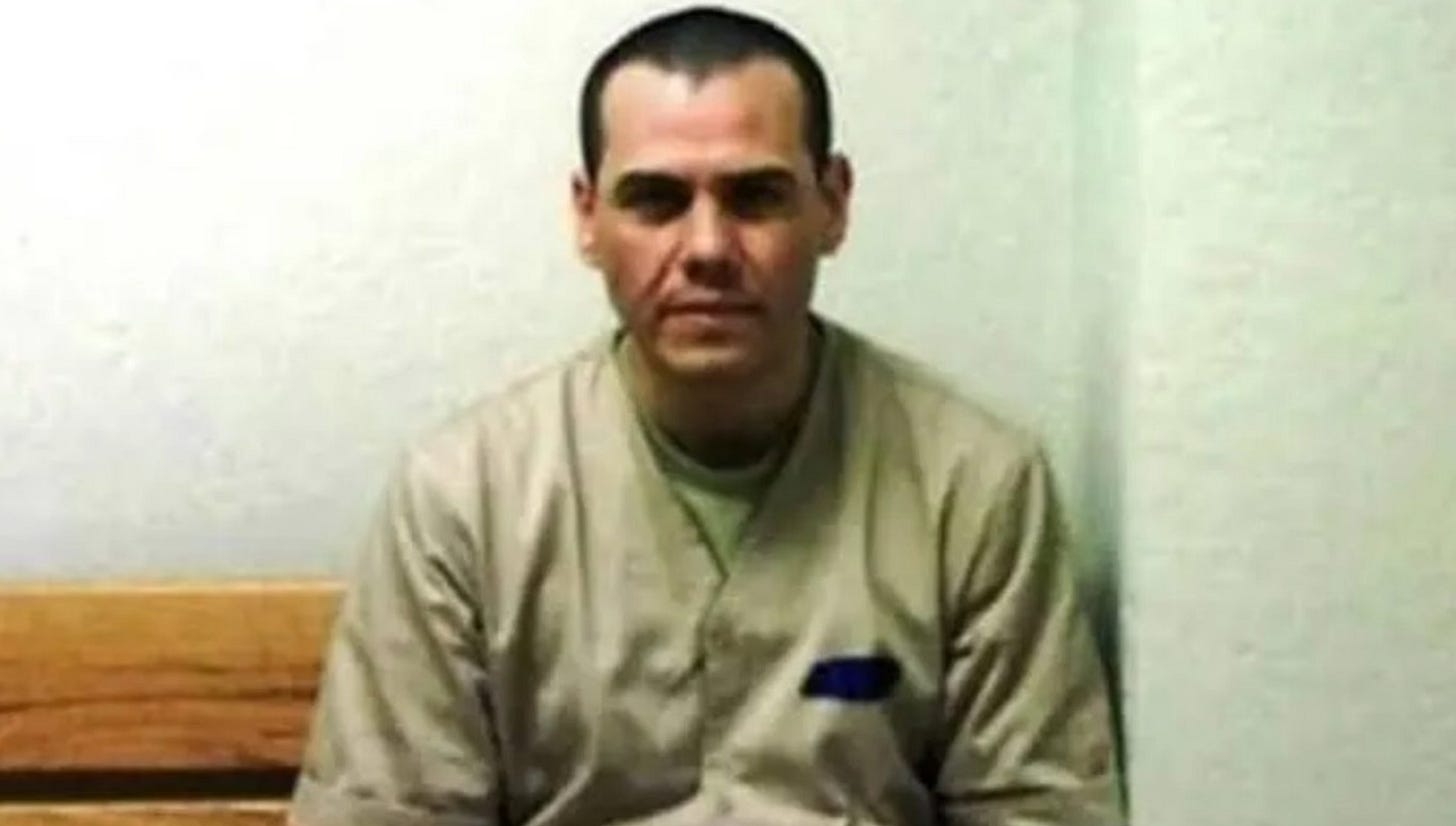

At the New York trial of Mexico’s former drug czar for cocaine trafficking in 2023, the judge issued a spicy ruling: witnesses could not be questioned about cannibalism. It was aimed at various gangsters who had worked with the deceased kingpin Arturo “The Beard” Beltrán Leyva, who engaged in human flesh-eating in santería rituals. The Beard’s lieutenant “El Grande” (The Big One), a hulking 6’7’’ ex-cop, took the stand and his blonde henchman “La Barbie” was on standby but was never called (perhaps because prosecutors decided Barbie was just too volatile).

The judge determined that these gangsters could not be asked about cannibalism because it would be “inflammatory and distracting” for the jury of middle-class New Yorkers, who were already nervous about a cartel case. El Grande opened the trial with a vivid description of handing tens of millions of dollars of Sinaloa Cartel cash to the accused Mexican official, Genaro García Luna. The jury ultimately found García Luna guilty, largely on the evidence of Grande and other narcos, and he will be sentenced next week.

Barbie and Big One are among a host of colorful villains who have cooperated with the U.S. government to convict cartel figures as the drug war rages and overdoses ravage America. As well as testifying in court, cooperators record drug deals with hidden devices, give up locations of wanted kingpins, and hand over cash and assets, sometimes worth tens of millions of dollars. In return, they get better prison conditions, early releases (sometimes just doing a few years behind bars or even no time) and can even earn reward money.

Prosecutors turn to these witnesses because it’s hard to convict cartel bosses and their political protectors. And snitches need an incentive as they risk being murdered by the cartels they testify against. But the rampant use of narco snitches raises serious questions.

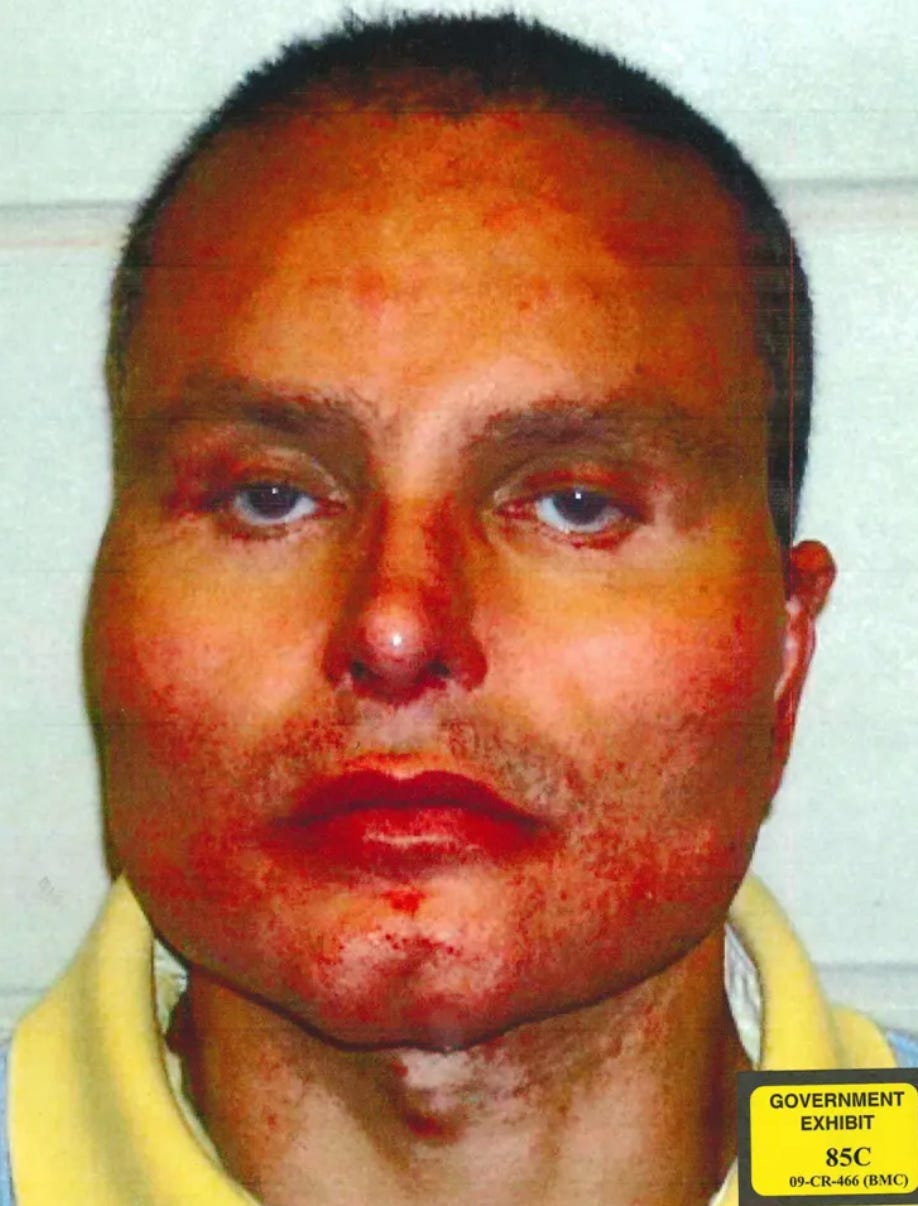

Is it ethical for the U.S. government to make deals with mass murderers? Colombian narco “El Chupeta” (Lollipop) witnessed against kingpin El Chapo and confessed to jurors that he ordered 150 “executions”; he was also notable for his plastic surgery face (below). Can their testimony be trusted? Are they simply using the U.S. government to take out rivals? And crucially, are prosecutors offering a career path that goes from drug trafficker to snitch, which young criminals figure out?

“It’s a system now they all know and understand,” says lawyer Jack Luellen who worked with the team defending Rubén Zuno Arce, a Mexican politician convicted of working with narcos. “The thing that worries me is you are giving immunity to generally speaking bad people too. What is the cost benefit analysis of giving benefits to many people to convict one person?”

There are also concerns about who the real U.S. targets are. Is it a win to make a deal with a kingpin to take out another kingpin? Or even to use a boss to take out his underlings? And there are questions about what the whole sordid affair actually achieves in terms of reducing overdoses and murders.

Deals are made with narcos in all the big cartels. In the showcase trial of El Chapo in New York in 2018-19, prosecutors wheeled out 14 cooperating witnesses including the brother and son of rival Sinaloa kingpin Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada. They are both now out of prison and brother Rey appeared on a popular Mexican music show in Los Angeles (he wants to be a songwriter).

Another kingpin, Osiel Cárdenas, created the Zetas paramilitary force that later committed thousands of murders, dissolving bodies in metal barrels. But Cárdenas had talks that involved handing over cash and likely informing on cohorts in Mexico. In a secret 2010 sentencing, uncovered by journalist Dane Schiller, a judge ordered Cárdenas to hand over a whopping $50 million and he got a 25-year sentence. This August, he was released after 21 years behind bars; some street crack dealers have done more time.

The deals around the arrest of drug lord El Mayo are also questionable. Details are murky but it’s alleged the Chapitos (sons of El Chapo) kidnapped the elderly kingpin, forced him onto a plane and flew him to agents in the United States in July. It could be a next-level of cooperation, an outsourcing of the rendition.

Two sons of El Chapo are now in U.S. custody, Joaquín Guzmán López (who was on the plane with Mayo) and Ovidio. Both could potentially cooperate with the U.S. government, even though the arrest of Ovidio cost the lives of Mexican soldiers and shut down Sinaloa. What’s more, the treachery against Mayo has sparked a bloody civil war inside the Sinaloa Cartel that has paralyzed the city of Culiacán and cost hundreds of lives.

With cooperators being so problematic, you may ask what is driving U.S. prosecutors to sign off on these deals? One factor is the money.

Follow the narco cash

In 2012, the U.S. government revealed where seized cash from Osiel Cárdenas was going. It said it was divvying up the bulk of $29 million it had got so far to…

Subscribe to read the rest of this story and the wealth of archive, including exclusive interviews with cartel operatives and maps of cartel territory, and become part of the CrashOut community.