Narco "El Plaga" Gives Me An Interview. Mexico Says He's In Prison But He Says He's Free.

"The Plague" describes the crazy life of the new sicario generation and the bloody infighting in the Sinaloa Cartel

(Para leer en español click aqui. To read in English on the website click here.)

Editors Note - Our compañero Luis Chaparro has done it again with an exclusive interview - and this time it’s even more controversial. The man known as “El Plaga” is not only an active narco, rather than one in witness protection; he’s officially in Mexican prison but says he’s out. Again, this is a difficult beat to cover with tough calls to make, but we believe that the information here is of big public interest and has to be out there. I have put half the interview for free, and half - including exclusive info on the fighting inside the Sinaloa Cartel - behind the paywall. It takes resources to cover this and for those with a paid subscription, know there will be a lot more to come and you are going to have better intel than anyone else in the room. The drug war is brutal but surreal and opaque and we hope this sheds some light. IG

After a shoot out in the border city of Mexicali, police arrested the boss of hit men known as “El Plaga,” or the “The Plague,” and he is now locked up in a Mexican federal prison, officials say. Yet the man I talk to on a video call claims to be El Plaga and says he is free and back operating in Mexicali, over the border from Calexico, California.

“They let me out,” he tells me as as he drives in a pick up truck at night. “Here I am, right where I have been, doing the same thing.”

He is slim and boyish, just 24 years old, but behind his youthful appearance is a hardened narco who has already been a decade in the Sinaloa Cartel and is a senior figure in a faction that controls a section of the U.S. border. He got his nickname, he says, as “he leaves no one alive, like a plague.”

The man on the video call looks like a photo of Plaga that appeared following his arrest in the state of Baja California in 2022. He shows me an ID with Cristian Alexis Mendoza Guillén, one of the names he was identified with by the police. And he knows complex details of the cartel.

Yet in the crazy narco war, it’s hard to know who or what to believe, so I will leave a caveat here and go deeper into the tangled details of the case below. Plaga (or the man claiming to be him) got in touch with me after I published an interview with another narco, Dámaso “El Mini Lic” López, which went viral. El Plaga works for a trafficker known as El Ruso (The Russian) who he refers to as Jefe R. Like Dámaso, El Ruso and Plaga are in a war with the Chapitos, the cartel faction lead by the sons of El Chapo. The latest fight has left a smattering of corpses in Baja California, Sonora, and Sinaloa.

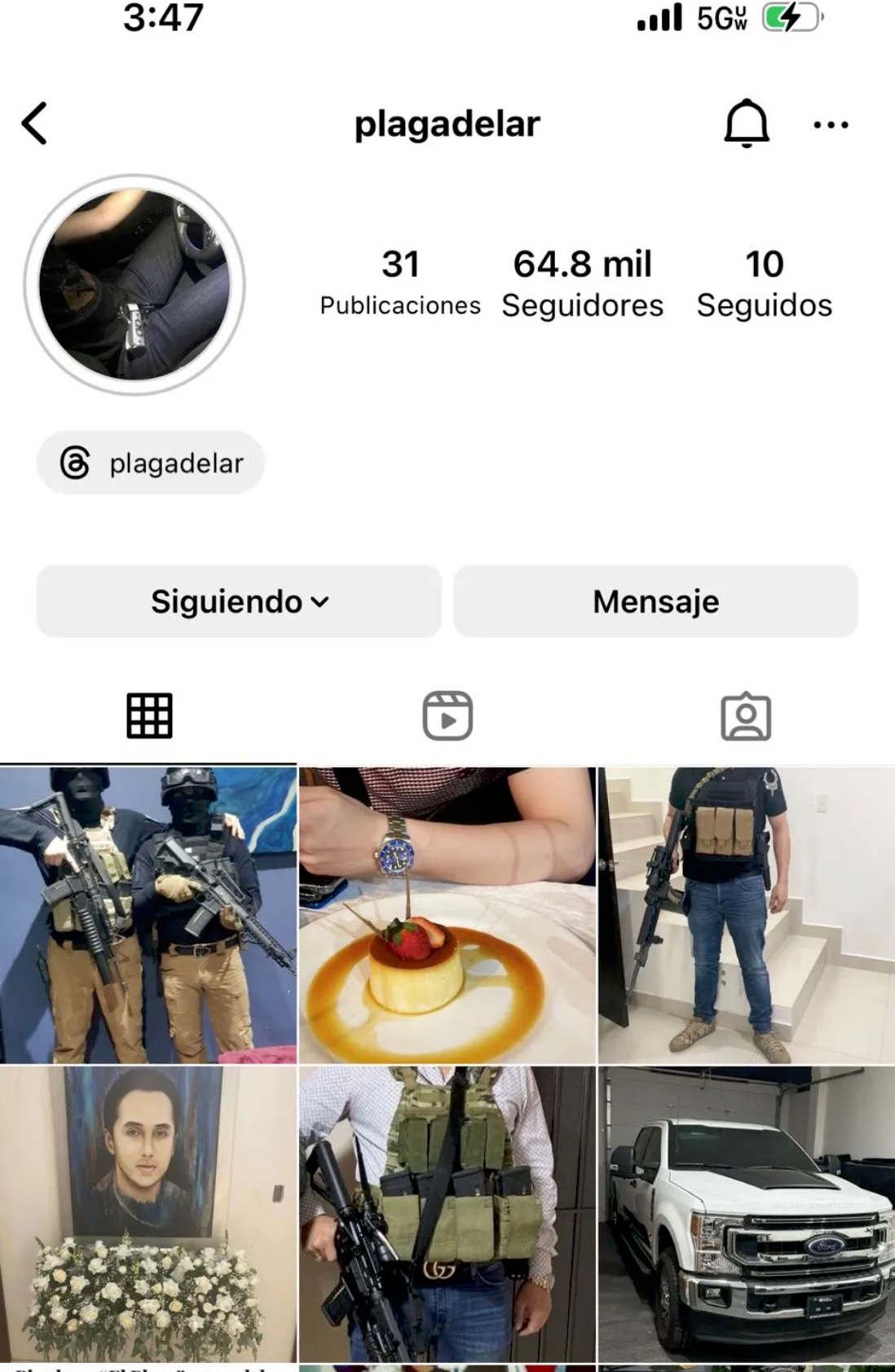

To make it even more surreal, Plaga has an Instagram account that he purportedly runs with 60,000 followers, which puts out pictures of guns, expensive watches, sports cars and music groups. He has several corridos, or drug ballads, about him. And he recently released a video of a pet monkey that his sicarios are using as a mascot (he gives details about it below). He’s not exactly making an effort to hide.

Plaga’s testimony is damning for Mexican law enforcement and its ability to restrain dangerous prisoners. It also gives unique insight into what drives infighting in the Sinaloa Cartel, causing a wave of bloodshed across northwest Mexico. And he gives colorful details about the crazy culture of the new generation of narcos, from their social media profiles to their links to the music business to their exotic pets.

Yet the case is explosive and confusing. And I need to unpack those details before we can get into the juicy account of his cartel life.

Plaga was arrested in November 2022 in Mexicali. As he tells me, he was leaving a bar after a night’s partying with a cohort “El Benny” in a car carrying a bunch of guns when the state police rolled up. Plaga stopped the car to try to avoid an incident. But his companion Benny (who police say was high on cocaine and fentanyl) just pulled out a rifle and started shooting and the cops returned fire. “I ran away when I saw that El Benny fell dead,” Plaga says.

Plaga was unable to make a deal with this particular group of state cops, who had just been shot at. “They don't align themselves, they don't settle with you. They work only for themselves and they are very tough,” he says. They gave him a severe beating and he got a mugshot taken while he was still bruised.

The arrest was widely reported because the “Rusos” are behind a lot of violence. Plaga was initially going to be charged in Baja California with attempted murder because of Benny shooting at the cops. But state prosecutors later said that he only had federal charges against him.

Then almost a year later, this October, the news magazine Zeta published that Plaga had failed to turn up for a court hearing and he was reported as “not located.” This prompted a response from the new chief prosecutor of Baja California, María Elena Andrade Ramírez who said that Plaga had been moved to federal custody.

“He was transferred to a maximum security prison,” she told a group of reporters. “The transfer was validated by judges…He was handed over in due form, we have the corresponding evidence, to federal prison number 13 in Oaxaca.”

I called to see if she stood by this statement. “I understand that this subject was indeed transferred to a federal prison and that he continues to be there,” she said.

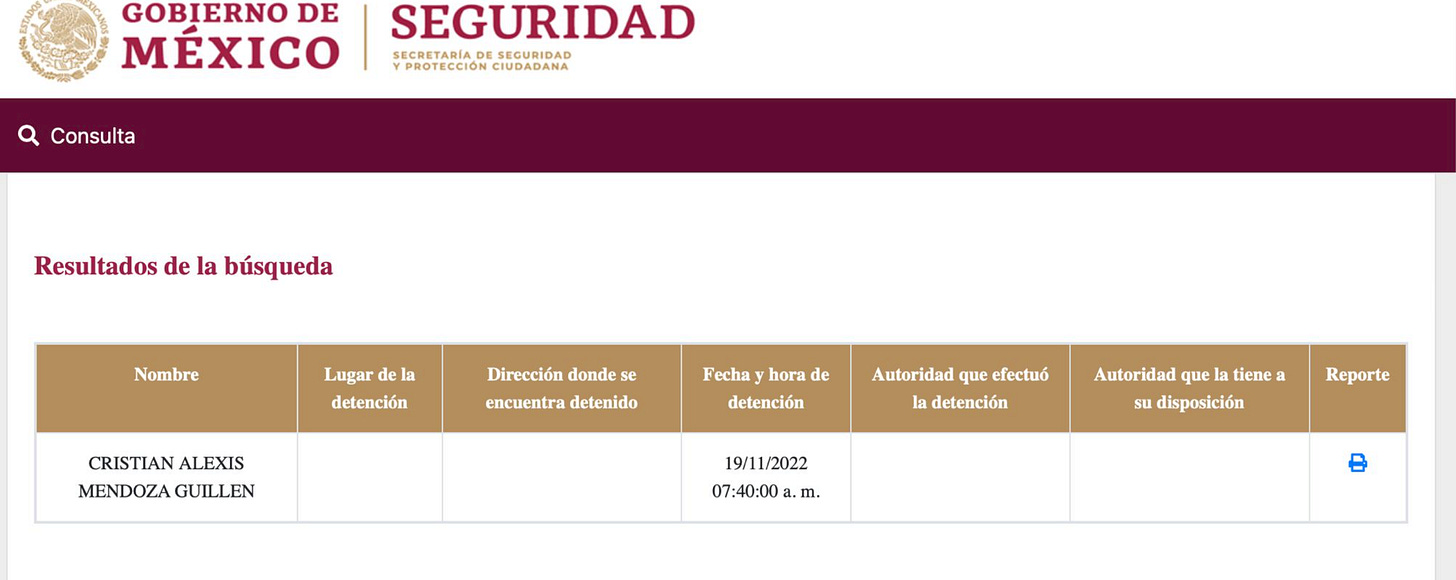

Still, I inputted his name in the federal inmate tracer and it showed only an arrest date without an indication of his location. I sent an email to the federal security ministry, which oversees the prisons, but it was not answered.

There could also be confusion about who really is or was in custody. Plaga was identified with several names, also including Eduardo René Robles López. And some of the photos purported to be of him look like they could even be different people.

On the video call, Plaga claims that his boss El Ruso managed to secure his release after just three days, but doesn’t go into exact details. “Jefe R negotiated with them to let me out and they took away all the charges,” he says, with a hint of pride. (Plaga could be referring to the state charges being dropped and there could still be federal charges against him).

The tangled web highlights Mexico’s opaque and dysfunctional justice system. But the fact that a dangerous criminal is on the streets would surprise nobody in Mexico. Prison escapes are frequent, from the high profile tunnel of El Chapo to mass break outs like when dozens of gang members escaped in Ciudad Juárez in January. Gangsters can also be let out because of dubious decisions by judges such as when the drug lord Rafael Caro Quintero was released in 2013 to the ire of the DEA.

Prisoners have even been found to come and go from jails. In 2010, a scandal erupted when it was discovered inmates in Durango were let out, carried out massacres in the neighboring Coahuila State, and then returned to sleep in their cells. They even used the guards’ guns to commit the murders.

Narco Gen Z: Instagram, Cumbia-Rap and Pet Monkeys

Plaga hails from Sinaloa, the cradle of Mexican drug trafficking, where he joined the ranks of organized crime at just 13, he tells me. Narcos being recruited at this tender age has become painfully common. In Tamaulipas, a 13 year old hit man known as Juanito Pistolas was celebrated in song but finally got his head blown off by soldiers when he’d just turned 17.

Plaga was attracted to the gangster life, he says, by the drug ballads of a group of Sinaloa Cartel killers dubbed The Anthrax. Like him, they have a disease metaphor; while critics call cartels a cancer, they also use the comparison themselves.

“I joined because of the corridos they made for Los Ántrax,” Plaga says. "I wanted to be an Anthrax.”

Many of these teenage gunslingers are treated as cannon fodder and lead short bloody lives. Plaga, however, survived and was recruited by a key operator of Mexico’s longest-running drug lord, Ismael “El Mayo” Zambada, in the state of Baja California. “There they gave me work. First in Tijuana and Tecate and then in Rosarito and Ensenada," he says.

He rose up in the cartel to become a head of hit men by the time he was 20, working for El Ruso (his real name is reported as Jesus Alexander Sanchez Felix, and for clarity, he’s not actually Russian).

Plaga represents a new generation of cartel thugs, coming of age in 2017 when the drug war first launched by Felipe Calderón had already been going on a decade. He came up amid social media, synthetic drugs and narco warfare that feels like it will never stop.

Many of the social media accounts that have emerged with the names of active narcos are obviously fake. But there are others that appear to be genuine, gaining tens of thousands of followers or more, including the one by Plaga. While they usually shy away from showing the narco’s faces (although some even do that) they show off guns, exotic animals, expensive watches, drugs and the scantily clad bodies of their girl friends. They use the platform to taunt their rivals.

Plaga recounts that following a prolonged battle in Sinaloa between the Rusos and Chapitos in 2020, the Rusos finally had to retreat back to Baja California. “El Nini [head of security for the Chapitos] wrote to me on Instagram after that making fun of the fact that they beat us,” Plaga says.

I ask him why the hell narcos post on social media when they are wanted. He retorts he is not showing actual crimes such as shootings and beheadings but just his “luxuries.” For the gangsters, social media gives them a chance to show off their wealth and build a fan base; in turn they encourage youngsters to their lifestyle.

The new generation of narcos are also close to a new generation of musicians. Peso Pluma, who is one of the most successful Mexican artists of all time with a style known as “corrido tumbados,” is alleged to have songs about the operatives of the Chapitos. Plaga meanwhile has several corridos about him, including one by a popular band called Revolver Cannabis that has almost two million views on YouTube. As the song goes: “I bring poison, I bring lead, I bring bullets; I am very toxic, if you get me in a bad mood.”

There is also a recent song in the new style of “cumbia-rap,” called El Plaga by the artist David Villavicencio. “I’ve got the gear; I’m a good aim; If it’s night or day; They ain't shit compared to me when it comes to combat,” it goes.

Plaga describes to me how the songs are mostly commissioned by the narcos they are talking about and the gangsters have to approve the lyrics before they are released. This again gives cartels a big influence on culture.

While narcos have long been into exotic animals, the new generation like to show them off on social media. In October, Mexican soldiers raided a ranch and seized two Bengal tigers of El Nini. Even more bizarrely, Mexican security forces got into a battle last year in Mexico State in which a spider monkey was shot dead. The ape was dressed up in a bullet proof jacket and camo like the sicarios it was with - and it even got a corrido about it.

Following this, Plaga’s crew got a monkey of its own and released video of it onto social media in October next to an expensive rifle. I ask him where he got the ape. “This monkey was given to me by my compadre,” Plaga tells me. “It wasn't mine, but it's one of the luxuries one can keep."

Rusos Versus La Chapiza

Plaga gives me the first public account of the modern infighting in the Sinaloa Cartel that has driven the bloodshed in northwest Mexico.