How the Gulf Cartel "Taxes" the US Border

The crime mob went from bootlegging via cocaine to oil and migrants. Importers now have to deal with it.

Juan Alberto Cedillo, Ieva Jusionyte and Ioan Grillo

Para leer en español click aqui.

Perched on the banks of the Rio Grande as it flows east into the Gulf of Mexico, the cities of Matamoros, Río Bravo, Reynosa, Camargo and Miguel Alemán form a major hub for importing U.S. goods into Mexico. They are opposite a network of cities that fill the southeast corner of Texas, from McAllen to Brownsville to Harlingen, which are built around trade with their southern neighbor. They are the also on the way to Mexico from Houston, which refines two-and-a-half million barrels of oil a day. Once over the border, it’s less than three hours to the business capital of Monterrey or 12 all the way to Mexico City. It’s a crucial path for goods and services traded between the U.S. and Mexico, which totaled $855 billion in 2022.

Yet there is a complicating factor on the route - the Gulf Cartel.

The crime mob taxes importers through control of the border cities and corrupt officials on its pay roll. As prices have been rising so have the quotas.

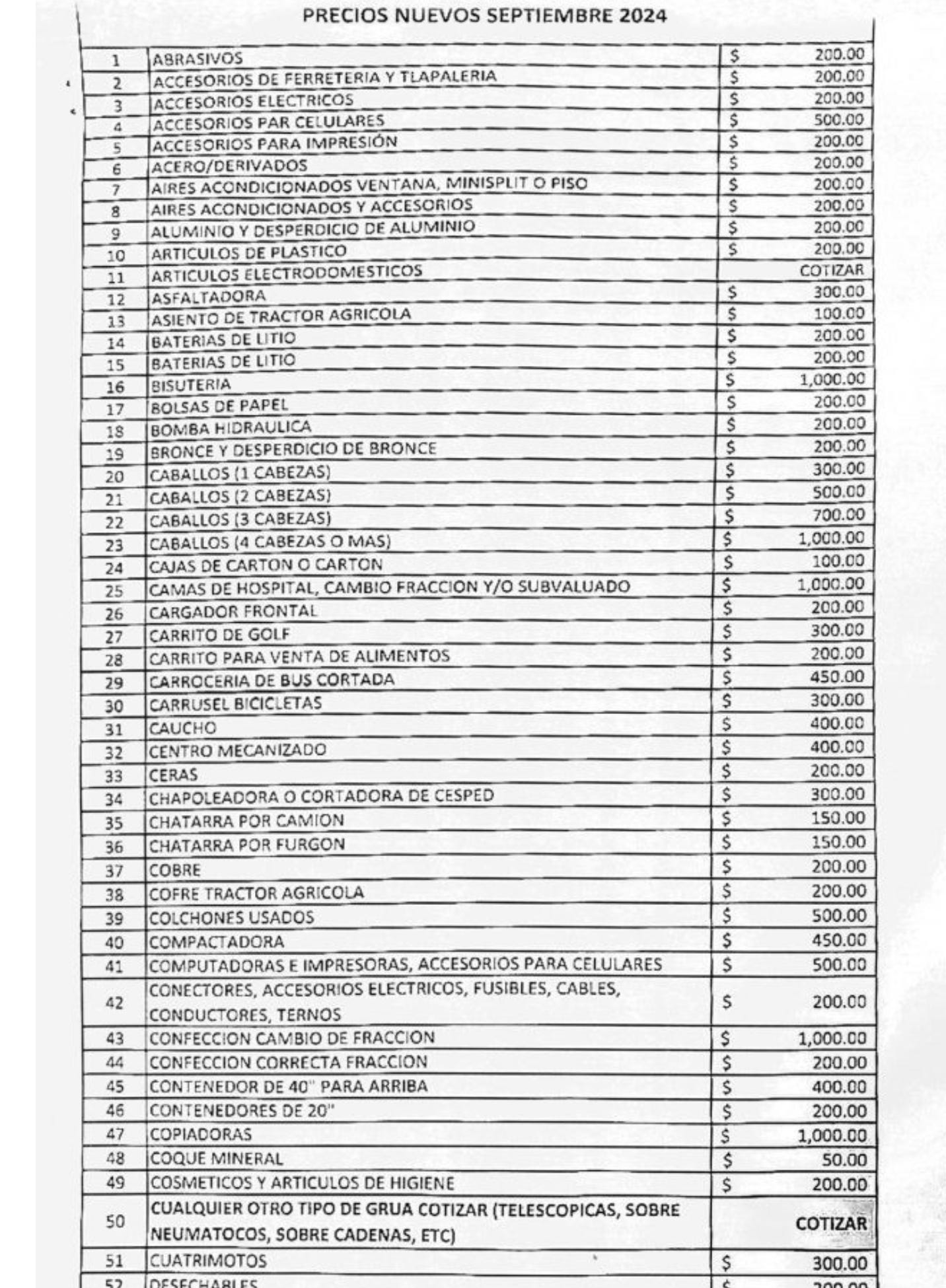

Last month, Mexico’s Reforma newspaper published a list of import shake downs that was alleged to be circulating in Matamoros. It lists 215 items, including everything from crates of cosmetics ($200) to horses ($300 a head) to jet skis (written as “yetsky”) for $400.

A Houston-based oil trader told CrashOut the cartel also charged quotas on tanker-trucks of refined gasoline. The rate has shot up sharply from $300 to $1,200 per tanker, he said. (Despite being an oil-producing country, Mexico imports tens of billions of dollars worth of refined gasoline every year).

The whopping level of trade translates to considerable earnings for the Gulf Cartel, or CDG, as it’s known. The cartel also reaps handsome profits from smuggling migrants north and from shaking down businesses large and small in its home state of Tamaulipas. And while it still moves dope, the corridor has become less important for narco trafficking itself perhaps because the cartel is making so much on its other rackets.

One of the oldest crime mobs in Mexico, the CDG has roots bootlegging alcohol during Prohibition and became a key force pumping America with cocaine from the 1980s. But now it has transformed into a curious federation of cells that operate heavily-armed paramilitary squads characterized by home-made fighting vehicles known as “monsters.”

While the CDG has a monopoly on its core territory, the different factions are constantly fighting amongst themselves, unleashing battles that terrify citizens. They also get into heavy firefights with Mexican soldiers, which shut down cities. It’s an ominous sign of what Mexican cartels have become and a threat to the booming commerce on the border.

“The CDG is killing the goose with the golden eggs,” said a taxi driver in Matamoros. “They are choking us.”

From Moonshine to Cocaine

In 2015, a new street was inaugurated in a poor neighborhood of Reynosa controlled by the CDG. The street was baptized Juan N. Guerra, which is the name of the gangster who founded the mafia almost a century ago.

Subscribe to read the full story and wealth of archive, including exclusive interviews with cartel operatives and maps of cartel territory. For the price of a cup of coffee, you’ll be the best-informed person in the room and be supporting true independent journalism.